Bringing an Iraqi American Perspective to the Big Screen: A Conversation with Weam Namou

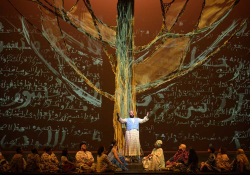

Born in Baghdad to an ancient lineage called the Chaldeans, Weam Namou is the author of fourteen books, including the novel Pomegranate. Set in the weeks before the 2016 US presidential election, a young, liberal Iraqi Muslim immigrant struggles to find her footing in a neighborhood of well-to-do, conservative Iraqi Christians. Namou is currently working on turning this novel into her first feature film. Here, from the filming location, she discusses the novel and its new life on screen.

Michelle Johnson: Pomegranate is set in Sterling Heights, a Detroit suburb containing “Little Baghdad.” Is this your neighborhood? The location where the film is currently shooting?

Michelle Johnson: Pomegranate is set in Sterling Heights, a Detroit suburb containing “Little Baghdad.” Is this your neighborhood? The location where the film is currently shooting?

Weam Namou: Yes, this has been my neighborhood for decades, and I love it here. Our Ninth District has the largest population of Iraqi-born individuals in the United States, and Michigan has the largest population of Chaldeans in the world, the majority of whom live in Sterling Heights. That includes almost all my family. After the start of the Iraq War in 2003, an estimated 50,000 Chaldeans arrived in Michigan, making our population today reach over 160,000.

Many people give Sterling Heights the nickname “Little Baghdad” since at every corner there is a family-owned producer market that has a tanoor inside which each morning makes fresh samoon (diamond-shaped pocket bread) and khoubuz (flat bread). There are restaurants galore, like Ishtar and Baghdad Restaurant, Kabob House, and Kabob Eden. There is Baghdad Market, Meat Baghdad, and Baghdad Tower Sweets. There are three mosques and three Chaldean churches, one in the city of Sterling Heights and two in adjacent cities.

Many Middle Eastern homes in Sterling Heights have multifamily living. A number of them include kitchen appliances in the garage, for the women who cook all day and do not want their homes to smell of fried food. Oftentimes there is also a couch in the garage, with a table, where people hang out, drinking tea, cracking sunflower seeds, just like back home when they would sit on the front porch and watch people and cars pass by.

Johnson: Within the community, there is sometimes tension between the Muslim Iraqi Americans and the Chaldean Iraqi Americans. How does the film illustrate or address this tension?

Namou: The film addresses and illustrates this tension with honest communication. Chaldeans are the indigenous people of ancient Iraq, the cradle of civilization, and they have been driven out of their lands by continuous centuries of wars, oppression, and genocide. The Islamic State’s 2014 destruction of their ancestral villages nearly wiped out all of them from their land, leading to much trauma and deep wounds.

The corruption and radical religious groups in Iraq have also caused atrocities for Muslim Iraqis, but we don’t hear as much about that. People tend to make assumptions and group individuals, and therefore, we’re unable to hear “the other’s” story. This causes our emotions to be set on fire, and so when we try to express ourselves, our pain and frustration spew out anger.

Communication is a healing art form.

Communication is a healing art form. My paternal aunt Hassina was a midwife and nurse in Fallujah city, which dates back to Babylonian times, was host to important Jewish academies for many centuries, and later became known as the city of mosques because of its over two hundred mosques. She was one of few Christians in that city, if not the only Christian. She lived there alone with her son after her husband went missing in some war. Mostly she delivered the babies of the wives and daughters of sheiks. My aunt worked for decades amongst tribes who loved and highly respected her. She also helped save a number of lives, especially the lives of newborn girls. Long ago, when Fallujah was just a small town, it was customary amongst Arab tribes for the father, if he so desired, to bury a newborn girl. Some men wanted to do just that, and my aunt was such an educated, smart, and compassionate woman that, through words and by citing the Koran, she, a Christian woman, was able to convince them not to.

Unfortunately, many people today are choosing to silence or even punish and hurt anyone who opposes their opinion rather than communicate with them. This type of behavior is dangerous, and it leads to violence and war. In the story Pomegranate, the women have the courage and intelligence to interact in brutally honest dialogues about things they disagree about. They learn a great deal in the process, about themselves and each other.

Johnson: In Pomegranate, Niran draws inspiration from her ideal, Enheduanna. Could you tell us about her?

Namou: Enheduanna (2285 to 2250 bce) is the world’s first recorded writer, yet barely anyone has heard of her, and she’s almost completely forgotten by her own people. The daughter of the great Mesopotamian king Sargon of Akkad, she was a princess, priestess, and poet. She had a considerable political and religious role in Ur, land of the Chaldeans, to which Chaldeans trace their roots. According to the Bible, Ur is the birthplace of the prophet Abraham.

Enheduanna wrote during the rise of the agricultural civilization, with its emphasis on gathering territory and wealth, on warfare, and on patriarchy. She offers a first-person perspective on the last times women in Western society held religious and civil power. Before her, it was customary for scribes not to sign their names, but she did sign hers, making it known to the world who the author was.

After her father’s death, the new ruler of Ur removed her from her position as high priestess. She turned to the goddess Inanna to regain her position, with the following hymn:

It was in your service that I first entered the holy temple,

I, Enheduanna, the highest priestess. I carried the ritual basket,

I chanted your praise.

Now I have been cast out to the place of lepers.

Day comes and the brightness is hidden around me.

Shadows cover the light, drape it in sandstorms.

My beautiful mouth knows only confusion.

Even my sex is dust.

Enheduanna lived at a time of rising patriarchy. It has been written that as secular males acquired more power, religious beliefs had evolved from what was probably a central female deity in Neolithic times to a central male deity by the Bronze Age. Female power and freedom sharply diminished during the Assyrian era, the period in which the first evidence of laws requiring the public veiling of elite women was made.

She wrote and taught about three centuries before the earliest Sanskrit texts, 2,000 years before Aristotle, and 1,700 before Confucius. In 1927 the British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley found the now-famous Enheduanna calcite disc in his excavations at the Sumerian site of Ur.

Johnson: From the book’s opening, we see the convergence of Niran’s love of Enheduanna and her desire for Facebook likes. Here in Little Baghdad, the ancient and contemporary are ever-present for Niran. How does this come through in the film?

Namou: It comes through Niran’s poetry, some of which is voiceover, her thoughts as she writes in her journal, and her expressions and postures in her sacred space, her bedroom. In these instances, we see a side to Niran that’s not observed by her family and community.

Middle Eastern women tend to keep their thoughts and feelings to themselves, and only share them with their most intimate inner circle. When they can’t even do that, they turn deep within as they find intricate ways to interweave what they want to do with what they have to do in order not to disrupt their family’s and tribe’s well-being. That’s what makes them mysterious.

Johnson: You wrote the novel in English, but as I visualize it as a film, I’m wondering if the film will be multilingual, for instance including the use of Aramaic with subtitles.

Namou: Yes, there’s definitely Arabic and Aramaic words with subtitles. I gave the actors the freedom to bring up native words that felt natural to them during the dialogue, and what came out of their lips was quite authentic, amusing, and oftentimes humorous.

I gave the actors the freedom to bring up native words that felt natural to them during the dialogue.

Johnson: Niran’s neighbors have Trump/Pence campaign signs and bumper stickers. The book is set before the 2016 election. Has the passage of time presented any challenges as you’re adapting the book to film?

Namou: Not really. We bought a Trump sign and set it on the lawn during filming and turned the sign over (opposite the street) after shooting—until the next time we needed to show it. We had a scene in the produce market and made sure that no one wearing a mask walked into the scene. WDIV-TV / Local 4 Detroit provided us with 2016 election footage, which we used on our TV.

The passage of time has actually been beneficial because when we said “Quiet on the set!” and “Action!” there was dead silence. That’s when the cast and crew were able to really listen to the dialogue in the film and hear the other side’s perspective.

Johnson: I’ve read online that this is the first Iraqi American feature film to be made by the community represented. Could you place this film in context with other films about the Iraqi American experience and perhaps talk about representation in film?

We’re left with stories that either show Iraqis as victims or terrorists, dehumanizing an entire population.

Namou: When you Google Iraqi American films, you will find dozens of films that were made from the perspective of an American citizen, usually military personnel or a US government official. Even if a few of the actors are Iraqi, the writer and director are not. We’re therefore left with stories that either show Iraqis as victims or terrorists, dehumanizing an entire population.

I have yet to find a feature narrative film made by an Iraqi filmmaker, let alone one whose cast is made up of the community it represents, let alone led by female talent. In Pomegranate, the majority of our Muslim Iraqi family is Muslim and of Iraqi background—except for Ismail Taher, who plays Ali, Niran’s brother (he is Muslim of Palestinian descent), and Fatima, Niran’s nine-year-old sister, is played by Jordyn Kashat, a Chaldean. The Chaldean family that lives across the street, which include Mary, her brother Matthew, and their mother Nisreen, are all Chaldean.

One thing that the cast continuously expressed is how they were able to relate to the script. For instance, Zain Shami, who plays Niran’s mother, is a hijabi Muslim woman in real life, and she was so excited to play a role that resembled her in real life.

The Greater Detroit area is home to one of the largest, oldest, and most diverse Arab American communities in the United States, with an estimated 350,000 people—over half of which are Chaldeans. Yet despite the large population of Arab Americans (roughly 3.7 million), our stories are underrepresented and stereotypical. This is partly due to the Arab/Chaldean American community not providing a strong vehicle to develop and encourage the arts, which results in the perpetuation of the patriarchal stereotype. Having come from war-torn lands where creativity is oppressed and, in some cases, even outlawed, our communities often operate in a defensive survival mode. There are also issues related to women that the community does not want to address.

Another reason why our voices are not heard is that the same institutions which claim they want “diverse and unique voices” have their own version of diversity and uniqueness. As a result, our children, particularly our daughters, rarely get a chance to view a version of themselves that’s relatable and inspirational, rather than pigeonholed.

Johnson: You’re shooting the film right now. Have there been any other-than-routine challenges, particularly in light of Covid-19?

Namou: We were strict with the number of people who could visit the set. We tested the cast and crew every morning, praying that no one would get Covid-19, which would have shut down production. Even prior to production, we feared that Covid-19 would cause us to change our shooting schedule to a later date.

Johnson: Is there already a soundtrack? Can you give us a preview of that?

Namou: We’re working on it! When we have something more solid, we’ll definitely share it with you.

Johnson: Excellent! You have interviewed filmmakers, which we can watch on your blog, and I’m wondering: What’s the question you would most like to be asked, and what’s the answer to that question?

Namou: I’d like to be asked, “What has been the biggest challenge in your film career?”

My answer: Getting the film industry to use their power and influence to support authentic Arab American stories rather than use Arabs, particularly Iraqis, as the backdrop for “exciting” and “exotic” thrillers. The negative portrayal they’ve supported for decades has been very harmful to our communities.

Johnson: When and where will people be able to watch Pomegranate?

Namou: We plan to complete editing the film by the end of 2021 and then start sending it to film festivals. You’ll get to watch it once it becomes available on a streaming channel, Inshallah, by mid-2022.

September 2021

Editorial note: Namou’s What to Read Now recommended reading list, “3 Books to Better Understand Iraq,” appeared in the July 2011 issue of WLT.

Born in Baghdad to an ancient lineage called the Chaldeans (Neo-Babylonians who still speak Aramaic), Weam Namou is the executive director of the Chaldean Cultural Center, which houses the first and only Chaldean museum in the world. She’s an Eric Hoffer award-winning author of fourteen books, an international award-winning filmmaker, journalist, poet, and an ambassador for the Authors Guild of America [Detroit Chapter], the nation’s oldest and largest writing organization. She hosts a half-hour weekly TV show, and she’s the founder of The Path of Consciousness, a spiritual and writing community, and Unique Voices in Films, a 501 (c)(3) nonprofit organization.

Born in Baghdad to an ancient lineage called the Chaldeans (Neo-Babylonians who still speak Aramaic), Weam Namou is the executive director of the Chaldean Cultural Center, which houses the first and only Chaldean museum in the world. She’s an Eric Hoffer award-winning author of fourteen books, an international award-winning filmmaker, journalist, poet, and an ambassador for the Authors Guild of America [Detroit Chapter], the nation’s oldest and largest writing organization. She hosts a half-hour weekly TV show, and she’s the founder of The Path of Consciousness, a spiritual and writing community, and Unique Voices in Films, a 501 (c)(3) nonprofit organization.