Prey: Behind the Scenes with Cinematic Comanches

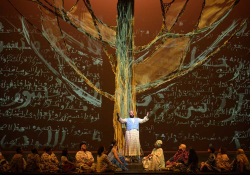

Hulu’s Prey—a narrative between a small band of Comanches, a humanoid predator, and French fur trappers on Comanche homelands—is the first film fully dubbed in the Comanche language. Dustin Tahmahkera co-consulted on the film with his aunt, Juanita Pahdopony, to whom the film is dedicated.

In the Numu tekwapu, the Comanche language, I say, Haa, haitsnu. Nu nahnia tsa Dustin Tahmahkera. I am a parent of four beautiful children, playwright of Comanche-centric theater, and professor of Native media and sound at the University of Oklahoma. My thanks to WLT editor Michelle Johnson for the invitation to share thoughts here as a consultant for the new Hulu movie Prey, or Kuhtaamia in Comanche, within the much older history of cinematic Comanches. Thanks also to the Comanche poet Sy Hoahwah for the connection and recommendation.

Photo courtesy of the author.

I come from a tradition where, as my late auntie and fellow Prey consultant Juanita Pahdopony said, “We’re obligated to tell our story.” To be obligated is to be bound by principles to do something, in this case, a storytelling of self and community that recognizes our principled roles in relationships, kinship, and accountability. May this story, then, honor Auntie and her love-filled teachings as an elder, mentor, artist, and consultant grounded in Comanche epistemology, knowledge, arts, and film. We descend from a long lineage of proud warriors and peacekeepers, caretakers and captive takers, and traders and raiders who established in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries what Finnish historian Pekka Hämäläinen calls “the Comanche empire” in northern Mexico and the southwestern United States of la Comanchería.[i] Lesser known is that we also come from generations of real-to-reel Comanches working in and around cinema in its production, performance, and perception as filmmakers, scriptwriters, actors, consultants, and critics.

From my great-great-great grandfather and last Comanche chief Quanah Parker’s co-starring role in the silent film The Bank Robbery (1908) to the story of his Comanche-captured white mother Cynthia Ann Parker inspiring The Searchers (1956) and other westerns, to my auntie LaDonna Harris adopting, or capturing, Johnny Depp during production of Disney’s The Lone Ranger (2013), real-to-reel Comanches have always been in the cinematic imaginary at the complex confluences of self-representing and getting represented by others. However, in the history of feature films, representations of Comanches are predominantly marked as hypermasculine and violent, vanquished, and vanished. “How many times,” as I ask in my recent book Cinematic Comanches, “must a people fall” on-screen “before more expanded, developed, and alternative stories of cultural resurgence and rising are produced”?[ii]

Real-to-reel Comanches have always been in the cinematic imaginary at the complex confluences of self-representing and getting represented by others.

So, when a former producer of Prey (then called “Skulls”) emailed me one day in late 2017 to discuss the film project that would stream five years and a pandemic later on Hulu, I agreed with cautious optimism. Would it humanize and progress toward what I call representational justice? Or would it regress into the Hollywood tradition of cultural erasure and injustice? Our first phone conversation quickly took an unusual turn. The producer said the big-budget movie would star a young Comanche woman going up against the predator. Like the one Arnold Schwarzenegger battled in the 1980s? Yes, that Predator. As long as no Austrians or Germans, like Henry Brandon in The Searchers and Two Rode Together (1961), got cast this time as Comanches, then I was listening. To hear of a Comanche lead in a feature film was very rare. To hear of a Comanche female lead was rarer in a Hollywood industry known to silence, sexualize, abuse, and otherwise dehumanize Native women’s on-screen representation. “The Pocahontas Perplex,” as Rayna Green once put it.[iii]

In response, I said you need Auntie ’nita, a strong elder Comanche woman, to come onboard and advise. She had just wrapped up lead consulting and language instruction for the first season of the AMC television series The Son, based on Philipp Meyer’s novel, which she also advised on as an administrator and art professor at Comanche Nation College. She formed close relationships on set with actors Zahn McClarnon, Elizabeth Frances, Richard Ray Whitman, and a long list of Comanche extras from back home playing Comanches on-screen. She also once co-starred in Lummi filmmaker Steffany Suttle’s 2008 documentary Fry Bread Babes about Native women’s representation in American pop culture.

Good creative conversations ensued between my auntie, me, director Dan Trachtenberg, and writer Patrick Aison. After we signed our nondisclosure agreements and received the first script, Auntie predicted, “This will be exciting.” She called it years before audiences, including Comanche viewers, began to rave about the thrilling and fantastical, yet culturally grounded, narrative in Prey between a small band of Comanches, a humanoid predator, and French fur trappers on Comanche homelands. She exemplified generosity in her feedback as she led the director and writer through the Comanche language, tribal specificity, and culturally appropriate character names.

We advised on technical aspects like clothing and weaponry and, as storytellers and writers ourselves, on story and character development. We introduced them to visual archives of Quanah’s daughter Wanada Parker and other ancestors and shared with them images of Comanche bowmaking by Willie Pekah and the art of Timothy Nevaquaya, Calvert Wayne Nevaquaya, and Eric Tippeconnic, including the latter’s painting Comanche Woman featuring a woman riding a horse while aiming her rifle acquired from, Tippeconnic explains, the French dating back to the 1750s. In Prey, Naru finds a Frenchman’s gun engraved with the year 1715, which was first seen in Predator 2 (1990) and prompted Trachtenberg and Aison to write a prequel involving the pistol’s origins.

Later, we worked with casting to set up a weekend of auditions at the Comanche Nation Complex. Auntie also introduced an early cut of her co-produced short film Thistle Creek (2020), which features, like my cousin Julianna Brannum’s 2014 documentary LaDonna Harris: Indian 101, strong Comanche women representing in front of and behind the camera. All the while, Trachtenberg and Aison genuinely listened and showed respect in contrast to an entertainment industry long known to exploit, or prey on, Indigenous ways and knowledge. Auntie continued to share more Comanche wisdom to their many follow-up questions before she crossed over in 2020. The following year, I wrapped up consulting and research and watched an early assembly cut of the film.

* * *

Set in the 1700s, during a time of Comanche borderlands dominance, Prey is a wicked and thrilling story. Although the film does not showcase an expansive version of Comanche empire, it does represent an intimate portrait of determination and relational accountability among a Comanche family, especially in the bond between Naru and her brother Taabe, and their extended band of relatives as they face the foreign predators (i.e., the humanoid alien and the gun-toting Frenchmen who slaughter the buffalo). Trachtenberg’s representation of strong and savvy female characters previously starred in his short Portal: No Escape (2011) and feature 10 Cloverfield Lane (2016). This time, Naru and other Comanches steal the show. Probably would have stolen horses, too, if there had been any on-screen. Perhaps in a sequel.

Set in the 1700s, during a time of Comanche borderlands dominance, Prey is a wicked and thrilling story.

In addition to the ingenuity and power of Naru and Taabe (who in one scene coolly counts coup on the alien by knocking off his mask), even Sarii (Comanche for dog), in true Comanche style, was badass. Naru’s close relationship with Sarii shows the two saving each other from dangerous encounters with predators and communicating with each other in verbal and performative ways that Timmy and Lassie would envy. Their scenes together took me back to Auntie’s culturally grounded painting When Comanche Women Could Fly and Animals Could Talk. Auntie’s and other Comanches’ relational stories of talking animals return to an ancestral time, as shown in Prey, of truly practicing the art of listening closely—tubitsinakukuru—to Comanchería soundscapes and spaces inhabited with various relatives. Some viewers may dismiss such sentiment as myth or tall tales, but our traditional stories suggest otherwise. And yes, Prey may be fictional, but it was made in part from the nonfictional creativity and labor of real-to-reel Comanches, including producer Jhane Myers, language consultants Kathryn Pewenofkit Briner and Guy Narcomey, dialogue actor Marla Nauni, research historian Jimmy Arterberry, and title sequence artist Nocona Burgess, all of whom know of cultural nuances and new possibilities for how Comanches appear, sound, and perform on-screen.

Prey may be fictional, but it was made in part from the nonfictional creativity and labor of real-to-reel Comanches.

As for the humanoid predator, he is referenced in the film’s opening line in a traditional Comanche approach to starting a story. Lead actor Amber Midthunder’s Naru says in English, “A long time ago, it is said, a monster came here.” In postproduction, Midthunder and other cast members returned to say their lines in Comanche, as producers had hoped to do and thanks to the tireless work of the Comanche Nation Language Department directed by Briner. For example, Naru refers to the “monster” as “Piamupits,” echoing the same term spoken by the late Comanche elder Mabel Simmons in the 2009 dramatic and humorous film short We Know What We Saw about Clarissa and Connie Archilta’s encounter with Piamupits. “My grandma,” the elder recalls, “told us a story about Bigfoot. Yeah, they see it around here. They call it Piamupits in Comanche. That means a big monster.” Previous films with Comanche words include Quanah Parker’s on-screen sign language in The Bank Robbery, audible brief uses of the language in the 1938 film series The Lone Ranger (director William Witney was from the Comanche Nation capital of Lawton), and more recent scenes of Comanche dialogue spoken in Comanche Moon (2008), The Lone Ranger (2013), The Magnificent 7 (2016), and The Son (2017–19). The result, however, for Prey: Hulu offers viewers the option to watch the entire movie in Comanche!

I think Auntie would be proud. She helped set forth an enriching and collaborative model for the film production’s foundational consulting and continues to inspire creative Natives, including Comanches who have always been fluidly in motion . . . and motion pictures. So, when you see Juanita Pahdopony’s name in the credits and (spoiler alert) see that the film is dedicated to her—a testament to her admirable and memorable impression—may you smile and remember that “we’re obligated to tell our story.” The film, and its recognizably Comanche representation, carries a lasting tribute to her everlasting legacy. May her beauty, generosity, and art continue to be a light in this world and beyond, and may her loving spirit be honored and reach and inspire generations to come.

U kuma kutu nu, Auntie. Always.

University of Oklahoma

[i] Pekka Hämäläinen, The Comanche Empire (Yale University Press, 2008).

[ii] Dustin Tahmahkera, Cinematic Comanches (University of Nebraska Press, 2022).

[iii] Rayna Green, “The Pocahontas Perplex: The Image of Indian Women in American Culture,” Massachusetts Review 16, no. 4 (1975): 698–714.