The Roar of the Wronged: Aravind Adiga’s White Tiger

After watching White Tiger, a writer contemplates the film alongside revolution in Egypt, Black Lives Matter protests, the film Parasite, and literary “complicated works of conscience.”

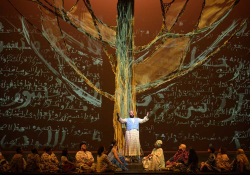

Born and raised in Cairo, Egypt, I felt a familiar sorrow watching the deprivations and heartache depicted in Netflix’s The White Tiger (2021). Based on the debut novel by Indian author Aravind Adiga—which won the Man Booker Prize in 2008―the movie is compellingly adapted by acclaimed screenwriter and director Ramin Bahrani (in turn, a good friend of Adiga’s and to whom the novel was dedicated). As close and imaginative readers know, it is notoriously difficult for movies to do justice to books, especially to make intelligent films that are faithful to the text. White Tiger is one of those happy exceptions, a work of art in its own right, where much of the force of the novel is not lost in its translation.

White Tiger is one of those happy exceptions, a work of art in its own right, where much of the force of the novel is not lost in its translation.

Ostensibly, this difficult film exploring difficult realities is about modern-day India, in a changing, global world, the attendant systemic injustices of its caste system and corruption of ideals at every level: moral, political, spiritual. Really, however, it’s a meditation on poverty and its sins, the abuses of those in power, psychological enslavement and liberation—as well as the many shades of moral gray we live with. In that sense, watching this darkly humorous film is as rewarding as reading a novel of ideas.

Netflix’s White Tiger invites meditation on lofty concepts such as free will versus predetermination, as seen through the lens of this great subcontinent, while unsentimentally attempting “to catch the voice of the men you meet as you travel through India—the voice of the colossal underclass . . . [inhabitants of] the Darkness” (the stated aim of Adiga for his novel). In this way, for example, one can substitute India for Korea, and you hear echoes in Tiger of 2019’s Oscar-winning black comedy Parasite—another sad, mad tale of the volatile relations between the haves and the have-nots and the cost of ambition at any price.

Is Balram more sinned against than sinning? Is the price he pays for his so-called liberation worth it?

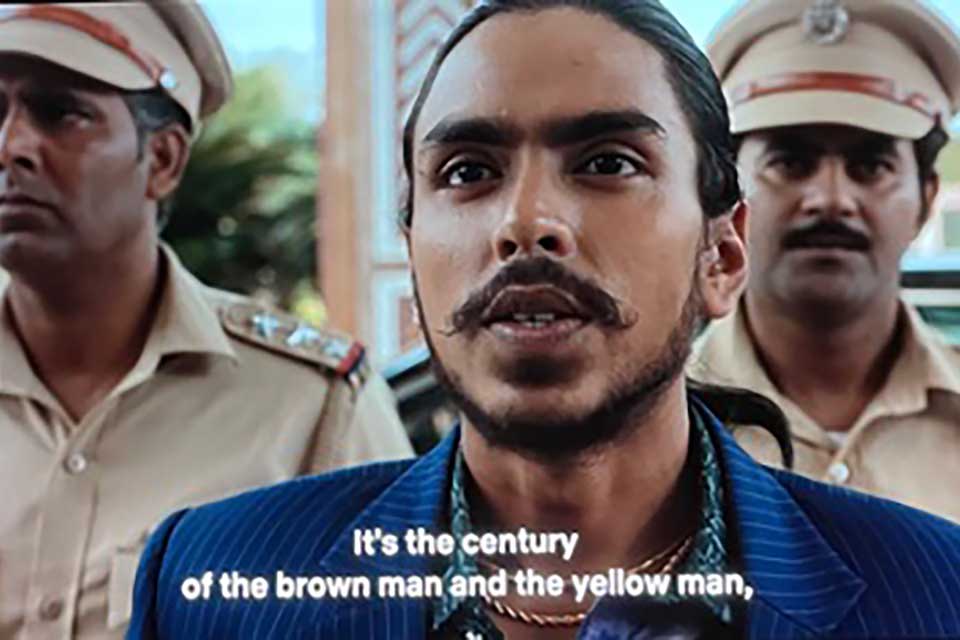

The cast of White Tiger is an impressive ensemble, portraying some depraved, power-hungry individuals that are easy to recognize and despise. Also in the mix are more complex, well-meaning but ultimately spoiled characters, whose privilege and bad behavior unwittingly enable more suffering, such as the wealthy, westernized and caste-questioning Pinky (portrayed by Priyanka Chopra Jonas) and Ashok (played by Rajkummar Rao). But it is the harder-to-judge antihero, Balram Halwai (given life by Adarsh Gourav), who carries the bulk of this heavy film’s weight on his back. Alternately innocent, obsequious, ambitious, and vicious, Gourav is mesmerizing as Balram on his journey from being a nobody to becoming Somebody. Is Balram more sinned against than sinning? Is the price he pays for his so-called liberation worth it? “We are made mysteries to ourselves by the Rooster Coop we are locked in,” Balram says in the novel, and the powerful leitmotif of the Rooster Coop is extended throughout this film.

“Do we loathe our masters behind a façade of love—or do we love them behind a façade of loathing?” This question, asked by Balram in the novel, survives intact in this film adaptation.

Watching White Tiger on Netflix the other night left me thinking, profoundly. I was transported back home to Cairo and to our desperate, glorious revolution (whose ten-year anniversary was this week). I also saw parallels with the massive Black Lives Matter protests that galvanized the nation and captured the imagination of the world, with their wounded warning: “No Justice, No Peace”―as true of the tortured race relations in the US as it is for the beleaguered Palestinian people. Human beings are the same everywhere, and oppression is antithetical to our nature.

Meditating further on Netflix’s White Tiger, I was put in the frame of mind of masterful works of literature that address vast and nuanced moral quandaries, such as Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, Jean Genet’s The Maids, and Rohinton Mistry’s A Fine Balance. Like White Tiger, these complicated works of conscience are rich in existential questions and uncompromising in their exploration of the darkness (or perversion, even) in the trying stories they tell. Despite the fatal flaws of their pitiable protagonists, they are not without dignity, humanity, light, and heroism, since the greater crime might be their unenviable circumstances.

Fort Lauderdale, Florida