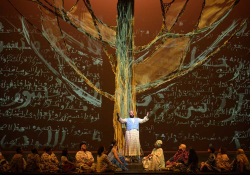

Where Do We Go Now with Quo Vadis, Aida?

A war refugee from Bosnia now living, writing, and teaching in Sweden reviews Quo Vadis, Aida?, the Oscar-nominated film about a UN translator in Srebrenica when the Serbian army takes over the town in July 1995. After considering both the praise and the criticism, he ultimately asks: Why are we fretting as if this movie is the first and last expression of the Bosnian genocide?

There is no other way for me but to be personal in my review of Jasmila Žbanić’s Quo Vadis, Aida? Being personal is the only way, for me, to be objective. After all, writing this, I’m wearing several hats: a survivor of war, a refugee, a writer, a literature professor.

Quo Vadis, Aida? takes place in eastern Bosnia in July 1995. Aida is a translator for the UN in Srebrenica at the time the Serbian army takes over the town, and her own family ends up among the thousands of civilians looking for shelter in the UN camp. The title comes from the famous episode in early Christianity when St. Peter, fleeing crucifixion in Rome, meets the risen Jesus who asks him Quō vādis? (Whither goest thou?), to which he replies, Rōmam eō iterum crucifīgī (I am going to Rome to be crucified again). Cross-cultural resonances abound when the Muslim Aida, as an insider to the negotiations between the UN and the Serb army, keeps running back and forth between men of power, hoping her meager access to political strategies will help her save her husband and her two sons.

Until very recently I did not want to see the film. I was quite determined not to see it. The reason for this was my previous knowledge of the process of its making (more specifically, its scripting). The movie is loosely based on the life of Hasan Nuhanović, the famous translator who survived genocide, testified against war criminals, became a chronicler of genocide, took the Netherlands to court for exposing Srebrenica to genocide, and won. Nuhanović wrote many times on his Facebook page about the troubles he had with Žbanić, the way she was taking what he called artistic liberties with his narrative, often toning down certain aspects of genocide through factual inaccuracies. Since then, he has commented on specific scenes he had seen on YouTube, for instance discussing certain problems of representation of the UN soldiers, but, as far as I know, he has not seen the entire movie. From what he’d written, as a writer, I could not understand how the narrative would require changes to the details he found essential.

Like all contemporary genocide denial, that discourse is like Schrödinger’s box.

The movie premiered at the Srebrenica Memorial Center in Potočari, next to the graveyards of all the thus-far-identified victims. Many of the people whose opinion I value and whose judgment I trust praised the movie. The highest praise came from every corner of the world, except for Serbia, of course. Genocide denial is very much a part of the mundane life there and in the so-called Republika Srpska within Bosnia. A few people whose opinions I highly respect as well were extremely disappointed by the movie, characterizing it as the rosy version of genocide and for that reason untruthful and uneducative. So imagine this: two groups are saying the movie is not truthful. The first consists of genocide deniers who say it is too harsh on the Serbs. The other argues that Žbanić failed to portray war crimes in their full scope and reality. It would be beyond ridiculous to even consider the first. Like all contemporary genocide denial, that discourse is like Schrödinger’s box. As long as the box is closed, in the perpetrators’ quantum minds, they can both deny it and boast about it. Genocide denial is a malady of our times and a continuation of genocidal intent. The second complaint is not insignificant. Out of respect for Nuhanović, if no one else, it should be taken seriously. And yet the movie is quite excellent.

Its aesthetic is soft, no doubt. The gore of the horrendous war crimes—mass executions, torture, mass graves, the moving of bodies from one pit to another in an attempt to cover up genocide—is implied. This is a common way to make something unbearable, seeable. Žbanić knows most of us and is not just considering the sentiments of international audiences who cannot see the horror head-on and do not want to see extreme war crimes aestheticized. I started watching it at home with my wife, and five minutes later she went to bed, even though it was only eight o’clock, and I was left alone in the darkness. She had trouble breathing all of a sudden. I understand that some wanted the movie to be educational in a different manner. They are suspicious of the strength of the “implied,” which for them is doomed to remain invisible to the new generations who will not watch it with the eyes brimming with memories like my wife’s. At best, these critics say, it might incite them to seek more facts about those few fateful days when more than eight thousand men and boys were systematically executed and hurled into Bosnian abysses, none of which is shown in the movie. This ought to be one legitimate way of interpreting the movie. At the same time, I could not deny that even this supposedly rosy version that tones down the culpability of the UN cuts deep. As the Bosnian-Swedish critic Sanjin Pejković writes, it is amazing how Žbanić manages to stay focused and clear and yet span the time before, during, and after the genocide, and how she tells a universal story without turning it into a collectivist pamphlet.

I could not deny that even this supposedly rosy version that tones down the culpability of the UN cuts deep.

I think she has much to thank the female lead, Jasna Đuričić, who carries the narrative in the most amazing fashion. She conveys not only the feelings of her own character but of all the other characters. She is our Frances McDormand. She is practically the only fully fledged face/character, the only one fully humanized and given serious depth in the ongoing dehumanization of the Bošnjak masses crying for help outside the UN compound. The scenes outside the safe zone, supposedly protected and controlled by the Dutchbat, quite amazingly show the exposure of the population, the betrayal by the UN (read: the world). And so do the scenes inside the buildings packed with refugees. The ways Žbanić juxtaposes the safe inside to the unsafe outside shows quite effectively that this dichotomy is complete bullshit and that the people inside are just as exposed. This is crystal clear, for instance, when the Serbian soldiers are allowed by the UN, although it is against the regulations, to come in with weapons and inspect the refugees, looking, surprise suprise, for terrorists. Sounds familiar. It should. Learn the lesson. At the same time, when Aida tries to save her family by putting them on the list of the UN staff, the command refuses, because, wait for it, it is against the regulations. The hypocrisy of the UN is visible for those who have eyes for it, but at the same time, as Nuhanović has pointed out, Žbanić makes the UN look merely pathetic, makes them the victims of international politics suffering from moral qualms when their commanders refuse to order airstrikes. In truth, Nuhanović claims, General Thom Karremans was very much onboard with this decision. The UN soldiers humiliated the refugees.

The strongest scenes for me were at the very end when Aida returns to Srebrenica and shows things few really talk about: the overwhelming horror of the afterlife of the survivors who have to live next door to war criminals, their children being taught by the perpetrators. This extended genocide is the reality of all returnees, effectuated through the normalization of political structures in which convicted or yet-unconvicted war criminals roam freely and create normal lives next to you and your family, and deprive you of the rights to identity, language, and proper civic life. Men and boys were killed, but the triumphalism of the genocide’s perpetrators was imprinted on women’s bodies. All this Žbanić tries to suggest to attentive viewers.

So what’s the final verdict? Is the movie, as many have said, Žbanić’s best work so far, a remarkable masterpiece worthy of all the prizes it has been nominated for (Oscars, Bafta, Golden Lion)? Or is it, as some compatriot critics have said, the rosy version of genocide that was better left unfilmed than filmed in any which way?

Why are we fretting as if this movie is the first and last expression of the Bosnian genocide?

There is no doubt that, despite some shortcomings with regard to historicity, the movie possesses plenty of qualities that make it a worthy expression of genocide and most definitely worthy of all the prizes it is getting (as I write this) and will get in the future. In the end, seeing the movie with different sets of eyes, with all the different hats, my question is this: Why are we fretting as if this movie is the first and last expression of the Bosnian genocide? The reason many survivors complain, I think, is because they wonder how many other opportunities there will be to tell this story on a global scale. Will global popular culture be simply satisfied and every other movie be dismissed as, Not another one about those little people. Will they stop whining? This fear is not just real, it is highly warranted. The industry of genocide denial has forced so many of us to constantly work on collections of narratives in all forms and all media. Surely anyone who needs deeper knowledge can turn to the hundreds of testimonies and historical documents collected in the Hague and the Srebrenica Memorial Center, but will they do it, or will they say we’ve seen Quo Vadis, Aida? the way many of us may say we’ve seen Schindler’s List or Life Is Beautiful and therefore know what we need to know about the Holocaust? We’ve seen Hotel Rwanda, and that’s plenty?

We should be bolder and not assume this is the first and last film about Srebrenica.

I want to use this wannabe review to suggest we should be bolder and not assume this is the first and last film about Srebrenica. There should be more. We should see Quo Vadis, Aida? as just one in the myriad of excellent attempts to preserve the memory of crimes we hope to God will never happen again. There should be more variation in our collective ways of relating our experiences and memories. All of them together should amount to something greater than the sum of their fragments. This movie is not about making it or breaking it. Praise and critique are necessary and are a part of the discourse of memory and history, but they should not be based on the idea that one expression is the be-all or end-all.

Go see Quo Vadis, Aida? I do not think you’ll be left unmoved. Or unlearned.

Stockholm