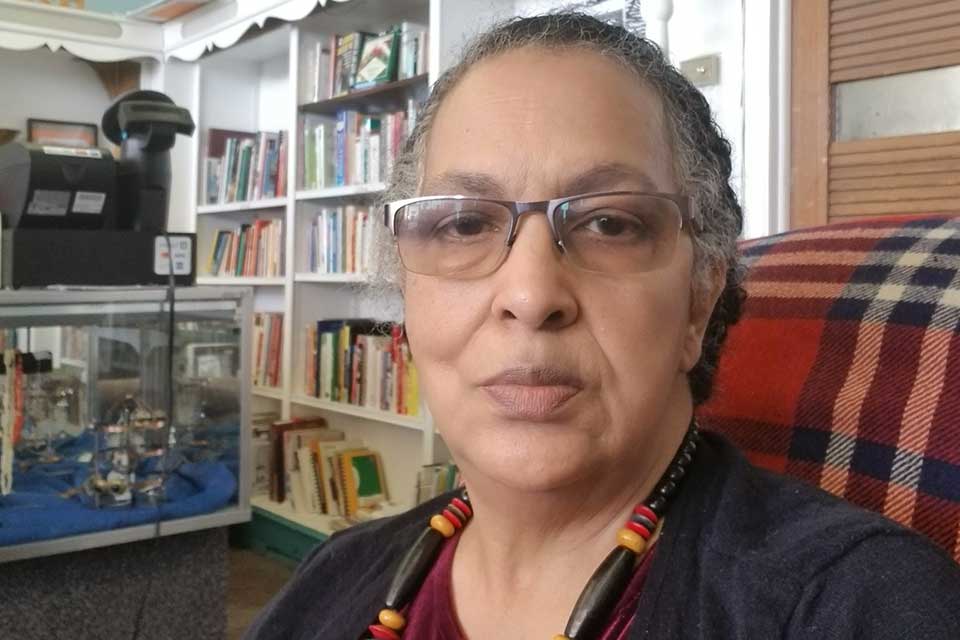

Nappy Roots Books, a Bastion and a Haven: A Conversation with Camille Landry

On a visit to an Oklahoma City bookstore, Alex Crayon finds more than books.

When I pulled into the snow-covered parking lot of Nappy Roots Books in northeast Oklahoma City, the first thing I noticed were the posters. Handwritten signs encouraging people to “Come in and Get Warm” and declaring “Masks Are Required Inside” hung taped to the glass-door entrance. In the window beside the door, signs proudly announced Nappy Roots as a Black-owned business supporting the Black Lives Matter movement, and flyers gave information about voting rights, clearing warrants, and chess club.

Not exactly Barnes & Noble—in the best way possible.

Nappy Roots Books is, if I must summarize, an intimate environment—not just a place. To call this bookstore simply a place would be to devalue it, to strip away the life imbued within the walls of this one-room store. Inside, tightly packed bookshelves hold books new and old, fiction and nonfiction, religious texts and travel companions. Two well-worn recliners flank a small table topped with a jar of cookies. A coffee-maker sits on a shelf near the register. And, in the center of the store, a long metal bookshelf holds every kind of Black literature: James Baldwin leans beside local writers, whose self-published books, says owner Camille Landry, are a source of empowerment for their authors. “There are people who said, ‘I did twelve years in the penitentiary, and I came out and wrote about it, and I want to share that.’ Random House is not going to pick up that book. But it’s on the shelf, and the author is speaking not only to other people who have had the same experience but to other people in the community who have not had that experience and who would otherwise struggle to understand it.”

It is this communal understanding that sits at the center of Nappy Roots Books’ mission, according to Landry. When I visited Nappy Roots—which has been struggling financially since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic—I got the opportunity to sit with her and talk about the store, about what makes it so much more than just a place to buy books.

It is this communal understanding that sits at the center of Nappy Roots Books’ mission.

Nappy Roots opened in June 2018 on Juneteenth, a day celebrating the full emancipation of slaves after the Civil War. This was no accident, as support and mobilization for the Black community in northeast Oklahoma City is at the heart of what makes Nappy Roots so special. “When we opened,” said Landry, lounging beside me in one of the recliners, “we were the only Black bookstore between St. Louis and Dallas. We exist because there was no place that was a repository of literature by, for, and about the African community. And there was no place where people could gather and do the work that needs to be done for this community.” She described myriad examples of services facilitated by Nappy Roots: financial literacy instruction, affordable funeral planning, religious counseling on end-of-life decisions, and women’s health information—to name just a few. “We put that information out there for the community. Other organizations do that, but they don’t do it in a way that’s culturally accessible, and they’re not always trusted. So we try to do it here.”

Her inspiration for Nappy Roots Books came from her teenage years, when she regularly visited a Black-owned bookshop in Chicago, where she grew up. “Ellis Books is the reason that I am who I am today. That store was the first place where I read a whole lot of things that formed the commitment that I have to the things that I do now. It meant everything to me.” She stressed the importance of the store as a cultural crossroads, a meeting place that educated her in ways that multiple universities failed to. “It was a room very much like this one [in Nappy Roots Books], just a little funky room on the south side of Chicago, filled with books stacked in used bookcases. I sat with people who were wiser than me, who were better informed than me, and Mr. Ellis said, ‘You need to read this. Come back and let’s talk about it.’ It was foundational. It made so many things happen in our community in Chicago.” Landry hopes to do the same changemaking with Nappy Roots in Oklahoma City, using the store as an epicenter of Black empowerment and as a fount of necessary resources for OKC’s Black community.

This homey bookshop is a place for harnessing this possibility, this potential, and for enacting communal improvement and change.

When I asked her about the power of the books themselves, she gave me a pointed example, describing her firefighter-obsessed grandson’s reaction to receiving a book featuring a multicultural cast of firefighters. “He did the happy dance. He said, ‘This is what I’m going to look like when I grow up! That’s me! This book is about me.’ That might sound trivial, but it is anything but trivial. Seeing a face that looked like his was everything to him. It told him that his dream is a possibility.” This possibility is the life-breath of Nappy Roots. As-yet untapped potential seems to float up and down the aisles, nestle between the books, wait beneath the pages. This homey bookshop is a place for harnessing this possibility, this potential, and for enacting communal improvement and change. As Landry told me, simply, “We try to be a place where ideas come to life.”

As I left Nappy Roots Books—with a newly bought copy of Things That Make White People Uncomfortable, by Michael Bennet, a former NFL player, and Dave Zirin—I felt the lingering touch of the bookstore: a soft, warm breeze of swelling feeling, a sensation not unlike the unique intimacy of running one’s finger along the spines of dusty novels and collections of poetry, as though tracing a line toward that one particular book which will, inevitably, captivate your imagination and, maybe, just maybe, inspire you to action.

University of Oklahoma