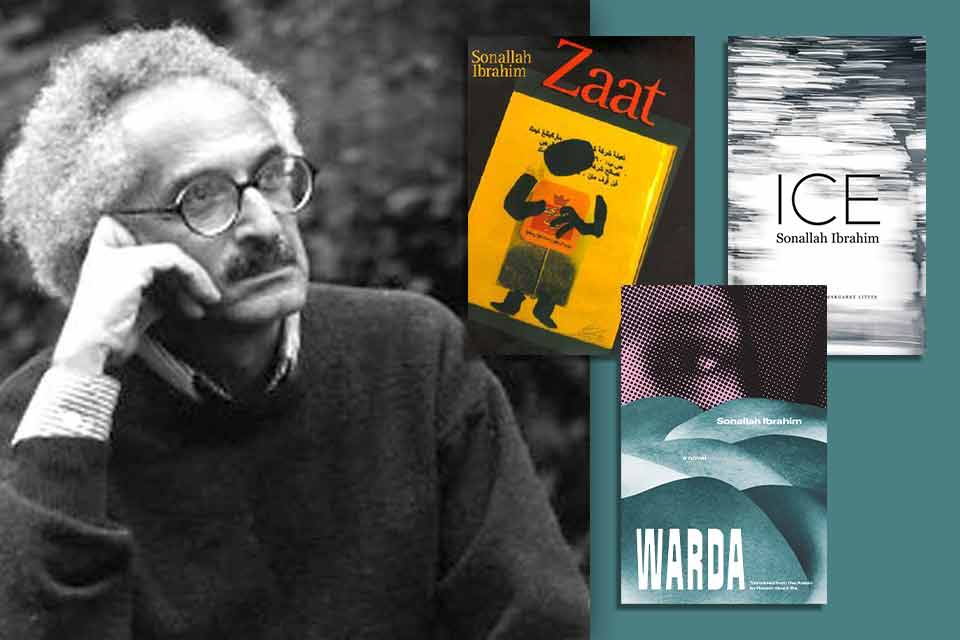

Remembering the Egyptian Novelist Sonallah Ibrahim: “Taking a Scalpel to the Communist Dream”

The author pays tribute to the prolific Egyptian writer Sonallah Ibrahim, best known as a leftist writer who began his career in the 1960s, during the reign of President Nasser.

When I first met Sonallah Ibrahim (August 3, 1937–August 13, 2025) in 2016—the Egyptian novelist with his shock of bushy white hair, granny glasses, and bemused expression—I was charmed by his quirkiness, wry humor, and wide knowledge of history, politics, and literature. I was interviewing him about his then-new novel, Berlin 69, which was published in Arabic in 2014. He came over for a few Stella beers at our place in Cairo—the interview felt like an informal chat between writers. He liked my book of bilingual short stories, Three Stories from Cairo (2011), which was translated into Arabic by the Egyptian poet Mohamed Metwalli, my husband. Offbeat expatriate characters clash with Cairo and traditional Egypt in humorous ways in my book: a theme that interested Ibrahim.

In the Arabic-speaking world, Ibrahim is best known as a leftist writer of the “Sixties Generation” who began his career during the period of President Gamal Abdel Nasser. Prolific, he published seventeen novels, four short-story collections, six children’s books, and three translations. Nine of his books have been translated into English: The Smell of It and Other Stories; The Committee; Beirut, Beirut; Zaat; Warda; Stealth; The Turban and the Hat; Ice; and 1970: The Last Days.

Ibrahim was born in 1937 during the waning years of the British occupation. His novel Stealth (2007)—translated by Hosam Aboul-Ela (2014) and narrated in present tense from a small child’s point of view—gives readers an insight into this era.

During our interview, Sonallah chose to sit in a large, comfy armchair with his back to the door. He mentioned that this choice was an exception. Normally, he sat with his back to the wall if he was outside of his house. Arrested in 1959 for distributing Communist leaflets and imprisoned for five years during Nasser’s rule, he was still traumatized from the experience. He said, “State security put me in front with the driver and the officer in the back kept beating me. Afterward, (it) was torture in prison for five years.”

Soon after he was released from prison in 1964, he published The Smell of It and Other Stories (1966), which was first translated by Denys Johnson Davies in 1971. The novel describes a disillusioned political prisoner who wanders around Cairo in a daze, alienated from daily life, like one of the Seven Sleepers of the Cave. The book was retranslated in 2013 by Robyn Creswell as That Smell with the addition of Notes from Prison—Ibrahim’s notes on cigarette papers written in prison.

Since we were talking about Berlin 69 for the interview, I asked him: “Did your experience in East Germany and Russia (1969–74) give you a useful perspective on Nasser’s version of socialism?”

“The dream was fantastic, but it remains a dream,” he said, waving his hands expansively.

He explained that other factors spoiled the Communist dream. “Other factors were not seen before, at the beginning of the experience—like the role of the state and the idea of one-party rule, defined as the vanguard class,” he commented. “People were enjoying the basic necessities, and you would never see a man sleeping on the street. Everyone had a job. You don’t enjoy freedom of expression; that is the dilemma.”

His novel Ice (2011), translated by Margaret Litvin (2019), uses a diary format to take a scalpel to the “fantastic dream” of communism through the eagle eyes of a sardonic Egyptian narrator who has come to study in Russia. The novel echoes some of the themes of Berlin 69: coping with paranoia and the fear of intelligence services, nostalgia for Egypt, transient relationships with foreign women, the hunt for scarce commodities, and a corrupt party elite. Ibrahim lived in Moscow during a crucial period in Egypt’s history, following the 1967 defeat and Egypt’s 1973 victory over Israel. Ibrahim recounts many details about the difficulties of living in Russia. For example, shortages of goods and commodities in a state-controlled economy led to absurd situations and bizarre behavior. When the main character is getting medical treatment, the doctor clearly states that he needs a new tire for his car!

Ice uses a diary format to take a scalpel to the “fantastic dream” of communism through the eagle eyes of a sardonic Egyptian narrator who has come to study in Russia.

Ibrahim observed that living abroad was beneficial for him as a writer. “It’s useful to look at your country from the outside,” he said, “to be in contact with other cultures and psychologies. Not to see your country as the center of the world.”

He toyed with the idea of staying in East Germany but said he was not comfortable writing in either German or English: “If you master the language, you can write in it. But one also has to understand the psychology and traditions of the culture. There are exceptions, like Nabokov.” Ultimately, he decided to return to Egypt.

The main character in Berlin 69 is a young Egyptian journalist who finds it difficult to write creatively in East Germany. When I asked him if being a journalist had stymied his own creativity, he said no. Instead, he pointed out the positive influence that journalism has had on literature “starting with Hemingway—he used the simple reporting in his telegraphic style and used different dimensions of texts.”

Besides The Smell of It and Ice, the novels Warda and The Turban and the Hat also utilize the diary form.

One of my favorites is Warda (2000), translated by Hosam Aboul-Ela (2021). The novel tells the little-known political story of the Dhofar Liberation Front, a Marxist group, whose main goal was to expel the British from Oman and Yemen after Egypt’s setback of 1967. (The Soviets and Chinese funded proxy wars in the Gulf in the 1960s and ’70s to gain influence there.) Rushdy, the main character, is a middle-aged writer searching for “Warda,” or Rose, the nom de guerre for an Omani activist he fell in love with while he was a student at Cairo University in the late 1950s. Rushdy visits his cousin in Oman to find out what happened to Warda. He receives her diary in a brand-name plastic bag in a series of mysterious handoffs. The novel alternates between Rushdy’s point of view in the 1990s and Warda’s in the 1960s (up until the end of the Dhofar Rebellion in the mid-1970s). Her diary gives the reader an insider’s view of a female rebel in a volatile political movement: an eclectic bunch, consisting of local tribespeople, herders, and Arab intellectuals.

Warda’s diary gives the reader an insider’s view of a female rebel in a volatile political movement: an eclectic bunch, consisting of local tribespeople, herders, and Arab intellectuals.

The novel The Turban and the Hat (2008), translated by Bruce Fudge in 2022, is an enjoyable read that gives modern-day readers the texture of everyday life in Egypt during Napoleon’s occupation of Egypt (1798–1801) and is informed by extensive historical research and Al-Jabarti’s chronicles. (Al-Jabarti was an Egyptian historian who wrote a firsthand account of the French invasion of Egypt in 1798.) The “diarist” in The Turban and the Hat is a student of Al-Jabarti’s who describes the struggle between French and Turkish forces for control of Egypt, the abuse of civilians by the occupiers, the lively intellectual atmosphere of Napoleon’s scientific expedition, the fear and the enforced quarantines during the bubonic plague, the collaboration of the Egyptian elite with the French occupiers, and Napoleon’s disastrous campaign in Syria. The narrator is sexually initiated by Pauline, a Frenchwoman who traveled with the expedition, who was reported to have an affair with Napoleon.

Ibrahim’s best-known novel in Egypt is probably Zaat (1992), which means “self” and was translated by Tony Calderbank in (2001). In it, Ibrahim alternated chapters of third-person narrative with newspaper headlines of the era, foregrounding politics with his use of headlines, sandwiching banal advertisements, scandals, and mundane details of daily life with big political events to highlight the hypocrisy of narratives promoted by the media. (The American writer William Burroughs used the “cut-up” technique, arranging bits of information to reflect a certain absurdity. This experimental approach was popular during the 1960s.) The novel was popularized by the entertaining television series Zaat (2013), with star Nelly Karim acting as the lead character Zaat, an ordinary Egyptian girl who struggles to complete her education during Nasser’s reign. Instead of marrying her sweetheart, she marries Abdel Mageed, an unimaginative dolt who seems to have better economic prospects. Against the backdrop of the Peace Agreement with Israel in 1979 and Sadat’s Open-Door Policy, it shows how ordinary Egyptians were squeezed by rising prices, unable to afford the deluge of consumer goods. Those who immigrate to the Gulf bring back Wahabi ideas about Islam, transforming Egyptian society in surprising ways that seem incompatible with the Egyptian spirit. The television series made Zaat’s story accessible to a mainstream Egyptian audience, who might not have read the experimental novel.

On the other hand, an international audience might be more familiar with The Committee (1984), translated in 2001 by Charlene Constable and Mary St. Germaine, reminiscent of Kafka, which focuses on the adventures of an unreliable narrator who is driven crazy by the byzantine bureaucracy during the time of Nasser.

Beirut, Beirut (1984), translated by Chip Rossetti in 2014, focuses on the Lebanese Civil War and also uses collage: newspaper headlines and excerpts from a film script. In one informal conversation, Ibrahim acknowledged to me how difficult it was for outsiders to penetrate the labyrinth of Lebanese politics and society.

1970: The Last Days (2024) was just translated by Eleanor Ellis. This novel intersperses newspaper headlines with the private musings of President Nasser from a second-person point of view in the last days before his death. One yearns for the point of view of others in the Free Officers’ Movement, however. Perhaps even Mohamed Naguib, one of the Free Officers who was sidelined and put under house arrest by Nasser, whose story has not been widely told.

Sonallah sent me a copy of the translation 1970: The Last Days last year with a short dedication that must have taken some effort because of his poor health. Frequently, he used to send us copies of books in Arabic from the avant-garde publishing house Dar El-Thakafa El-Gadidda, which he had run since 2008, when Mohamed Youssef El-Guendy, his wife’s first husband, had died. El-Guendy established the publishing house in 1968.

I remembered our visit to his flat in Heliopolis in 2017. He had written a blurb for my novel, and we were going to pick it up. We didn’t know if we should go or not because it was raining—a minor catastrophe in Egypt! He called and urged us to come: “It’s not raining here!”

A rope with a vegetable basket—known as a sabat—dangled from the stairwell. Many apartment dwellers lower the sabat down to those below for deliveries. Much public housing built during the Nasser era did not have elevators—later, landlords refused to spend the money to install them. We started the climb to the seventh floor. He and his wife, Laila, had lived there for decades—and his stepdaughter, Nadia, remembered how he had carried her up the stairs when she was little.

Laila had long, white hair, intelligent eyes, and a pleasant smile, and it wasn’t hard to imagine her as a young woman. She was self-deprecating and claimed she was “just a housewife,” but she was fluent in English and held a degree in English literature and Egyptology from Cairo University. She shared Sonallah’s left-wing political sympathies, and they had married in 1975. While Laila was away working as a tour guide, Sonallah cared for his stepdaughter, Nadia, since he was at home, writing. He read her bedtime stories when she was young and later encouraged her to pursue her doctorate in molecular biology.

“Sonallah was in the kitchen all afternoon!” Laila said. “I hope you’re hungry.”

It was a modest flat, with books stacked in every nook and cranny. We sat in a cozy living room in front of a low coffee table. The table was crammed with a variety of delicious mezze dishes. I was touched that he had gone to so much trouble since his ankles were swollen. He longed for a beer. “I’m on medication,” he said, pointing to his ankles. “All we do is go to doctors.” But he kept popping open the beers for me and my husband. He believed my novel was good—and would eventually be published.

The table was crammed with a variety of delicious mezze dishes. I was touched that Sonallah had gone to so much trouble since his ankles were swollen.

When the novel was published in 2022, we arranged to visit him and give him a copy of the book, Confessions of a Knight Errant, and a copy of our translation of Mohamed’s collection of poetry, A Song by the Aegean Sea. Nadia and her husband had helped Sonallah and Laila move from Heliopolis to their building in Mokattam Hills during the Covid pandemic in 2020. We got lost and had to call Nadia to find the building. Sadly, Laila had recently died.

It was an airy flat with nice light; a sliding glass door led to a large terrace.

He couldn’t hear well, and it was difficult to communicate with him. Nadia explained that he didn’t like to wear his hearing aid! He was very frail.

His ten-year-old granddaughter was also there, playing with a cat.

Sonallah directed us to the terrace with his cane. “I prefer the fresh air here.”

We stood outside for a moment and looked at the expansive sky, the Mokattam plateau in the distance. The sunlight was dimming.

Cairo