Writing Place

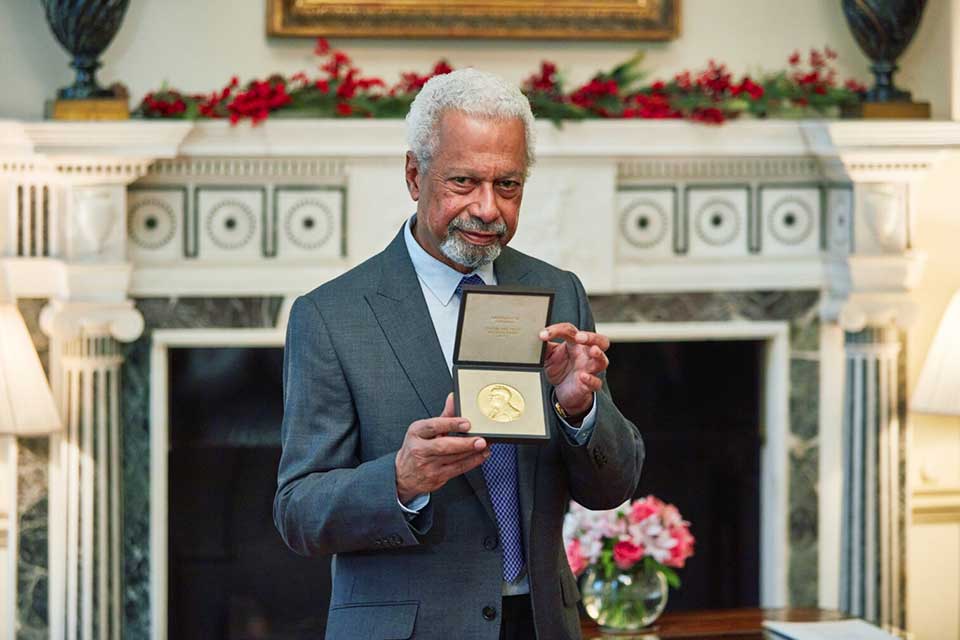

Earlier this week, Abdulrazak Gurnah received the 2021 Nobel Prize in Literature from Swedish ambassador Mikaela Kumlin Granitshe in London. His prize lecture, given on December 7, can be found here. In commemoration of the occasion, we are honored to reprint the following essay, which first appeared in the May 2004 issue of WLT.

It was in the first few years of living in England, when I was about twenty-one or so, that I began to write. In a sense it was something I stumbled into rather than the fulfillment of a plan. I had written before that, while still a schoolboy in Zanzibar, but those efforts were playful, unserious tasks, to amuse friends and perform at school revues, done on a whim, or to fill idle hours or to show off. I never thought of them as preparatory to anything, or thought of myself as someone aspiring to be a writer.

My first language is Kiswahili, and unlike many African languages, it was a written language before European colonialism, although this is not to say that the literate mode was predominant. The earliest examples of discursive writing date back to the late seventeenth century, and when I was an adolescent, this writing still had meaning and use as both writing as well as part of the oral currency of the language. The only contemporary writing in Kiswahili that I was aware of, however, were short poems published in newspapers, or popular story-programs on the radio, or the very occasional book of stories. Many of these productions had a moralizing or farcical dimension intended for populist consumption. The people who wrote them also did other things: they were teachers or civil servants perhaps. It was not something that occurred to me that I could do, or should do. Since then, there have been new developments in Kiswahili writing, but I am talking about my perceptions then. I could only think of writing as this occasional and vaguely sterile activity, and it never occurred to me to try my hand at it except in the frivolous way I described.

In any case, at the time I left home, my ambitions were simple. It was a time of hardship and anxiety, of state terror and calculated humiliations, and at eighteen all I wanted was to leave and find safety and fulfillment somewhere else. I could not have been more remote from the idea of writing. Starting to think differently about writing in England a few years later had to do with being older, thinking and worrying about things that had seemed uncomplicated before, but in a larger part had to do with the overwhelming feeling of strangeness and difference I felt there. There was something hesitant and groping about this process. It was not that I was aware of what was happening to me and decided to write about it. I began to write casually, in some anguish, without any sense of plan but pressed by the desire to say more. In time, I began to wonder what the thing was that I was doing, so I had to pause and deliberate and think about what I was doing as writing. Then I realized that I was writing from memory, and how vivid and overwhelming that memory was, how far from the strangely weightless existence of my first years in England. That strangeness intensified the sense of a life left behind, of people casually and thoughtlessly abandoned, a place and a way of being lost to me forever, as it seemed at the time. When I began to write, it was that lost life that I wrote about, the lost place and what I remembered of it. In a way, I was also writing about being in England, or at least about being somewhere so unlike the place in my memory and in my being, a place safe enough and far enough away from what I had left to fill me with guilt and incomprehensible regrets. And as I wrote, I found myself overcome for the first time by the bitterness and futility of the recent times we had lived through, by all that we had done to bring those times upon ourselves, and by what then seemed a strangely unreal life in England.

Traveling away from home provides distance and perspective, and a degree of amplitude and liberation. It intensifies recollection, which is the writer's hinterland.

There is a familiar logic in this turn of events. Traveling away from home provides distance and perspective, and a degree of amplitude and liberation. It intensifies recollection, which is the writer's hinterland. Distance allows the writer uncluttered communion with this inner self, and the result is a freer play of the imagination. This is an argument that sees the writer as a self-sufficient cosmos, best left to work in isolation. An old-fashioned idea, you might think, a nineteenth-century romantic self-dramatization of the author, but it is one that still has appeal and endures in a variety of ways.

If one way of seeing distance as helpful to the writer pictures him or her as a closed world, another sees distance as liberating a critical imagination. This second argument even suggests that such a displacement is necessary, that the writer produces work of value in isolation because he or she is then free from responsibilities and intimacies that mute and dilute the truth of what needs to be said, the writer as hero, as truth-seer. If the first way of seeing the writer's relationship to place has echoes of nineteenth-century romanticism, the second recalls modernists of the early to middle decades of the twentieth. Many of the major writers of English modernism wrote far from home in order to write more truthfully as they saw it, to escape a cultural climate they saw as deadening.

There is also an argument the other way: that in isolation among strangers, the writer loses a sense of balance, loses a sense of people and of the relevance and weight of his or her perceptions of them. This is said to be especially true in our post-imperial times, and of writers from territories that were former European colonies. Colonialism legitimized itself by reference to a hierarchy of race and inferiority, which found form in a number of narratives of culture, knowledge, and progress. It also did what it could to persuade the colonized to defer to this account. The danger for the postcolonial writer, it seems, is that it might have worked, or might come to work, in the alienation and isolation of a stranger's life in Europe. That writer is then likely to become an embittered emigre, mocking those left behind, cheered on by publishers and readers who have not abandoned an unacknowledged hostility, and who are only too happy to reward and praise any severity on the non-European world. In this argument, writing among strangers means having to write harshly to achieve credibility, to adopt self-contempt as a register of truth, or otherwise to be dismissed as a sentimental optimist.

Both arguments—distance is liberating, distance is distorting—are simplifications, although that is not to say they do not contain traces of truth. I have lived my entire adult life away from my country of birth, settled among strangers, and cannot now imagine how I might have lived otherwise. I sometimes try to do so, and am defeated by the impossibility of resolving the hypothetical choices I present to myself. So to write in the bosom of my culture and my history was not a possibility, and perhaps it is not a possibility for any writer in any profound sense. I know I came to writing in England, in estrangement, and I realize now that it is this condition of being from one place and living in another that has been my subject over the years, not as a unique experience that I have undergone, but as one of the stories of our times.

I believe that writers come to writing through reading, that it is out of the process of accumulation and accretion, of echoes and repetition, that they fashion a register that enables them to write.

It was also in England that I had the chance to read widely. In Zanzibar, books were expensive, and bookshops were few and undernourished. Libraries, also few, were meager and dated. Above all, I had no knowledge of what I wanted to read, and took what turned up in its haphazard way. In England, the chance to read seemed limitless, and slowly English came to me to seem a spacious and roomy house, accommodating writing and knowledge with heedless hospitality. This, too, was another route to writing. I believe that writers come to writing through reading, that it is out of the process of accumulation and accretion, of echoes and repetition, that they fashion a register that enables them to write. This register is a delicate and subtle matter, not always a method that can be described, although literary critics are dedicated to doing so; not an instrumental program that advances a story, but when it works, it is a complex of narrative moves that is appropriate and persuasive. I do not wish to make a mystery, to suggest that writing is impossible to speak about or that literary criticism is a self-delusion. Literary criticism educates us about the text and about ideas that go far beyond the text, but I don't think that it is through criticism that the writer finds the writing register of which I am speaking. That comes from other sources, central to which is reading.

The school education I received in Zanzibar was a British colonial one, even though by the last stages of it we were briefly an independent, even a revolutionary, state. It is probably true that most young people go through school acquiring and storing knowledge that has no meaning for them at the time, or that seems institutional and irrelevant. I think it was probably more puzzling for us, and so much of what we learned made us seem incidental consumers of material meant for someone else. But as with those other schoolchildren, something useful came out of it all. What I learned from this schooling, among many other valuable things, was also how the British looked at the world and how they looked at me. I didn't learn this at once, but over time and on recollection, and in the light of other learning. But that was not the only learning I was doing. I was learning from the mosque, from Koran school, from the streets, from home, and from my own anarchic reading. And what I was learning in these other places was at times flatly contradictory to what I was learning at school. This was not as disabling as it might sound, though it was sometimes painful and shaming. With time, dealing with contradictory narratives in this way has come to me to seem a dynamic process, even if by its very nature it is a process first undertaken from a position of weakness. Out of it came the energy to refuse and reject, to learn to hold on to reservations that time and knowledge will sustain. Out of it came a way of accommodating and taking account of difference, and of affirming the possibility of more complex ways of knowing.

So when I came to write, I could not simply shuffle myself into the crowd and hope that with luck and time my voice would perhaps be heard. I had to write with the knowledge that for some of my potential readers, there was a way of looking at me which I had to take into account. I was aware that I would be representing myself to readers who perhaps saw themselves as the normative, free from culture or ethnicity, free from difference. I wondered how much to tell, how much knowledge to assume, how comprehensible my narrative would be if I did not. I wondered how to do all this and write fiction.

Of course, I was not unique in this experience, although the details always feel unique as one frets at them. It is arguable that it is not even a contemporary or particular experience in the way I have been describing it, but one that is characteristic to all writing, that writing begins from this self-perception of marginality and difference. In that sense, the questions I am raising are not new questions. If they are not new, however, they are firmly inflected by the particular, by imperialism, by dislocation, by the realities of our times. And one of the realities of our times is the displacement of so many strangers into Europe. These questions, then, were not only my concern. While I was worrying away at them, others who were similarly strangers in Europe were working on problems just like these at the same time and with huge success. Their greatest success is that we now have a more subtle and delicate understanding of narrative and how it travels and translates, and this understanding has made the world less incomprehensible, has made it smaller.

University of Kent

Editorial note: First published in World Literature Today 78, no. 2 (May–August 2004): 26–28.