The Testament of Gjon Muzaka

On June 3, 1510, the graying Arbërian prince Gjon Muzaka was sitting at his desk.[i] He had the vertiginous feeling that his eyes were unshakably fixed on some clandestine object that both invigorated him and made him shudder.

He was turning fifty-two, but he felt as old as a patriarch.

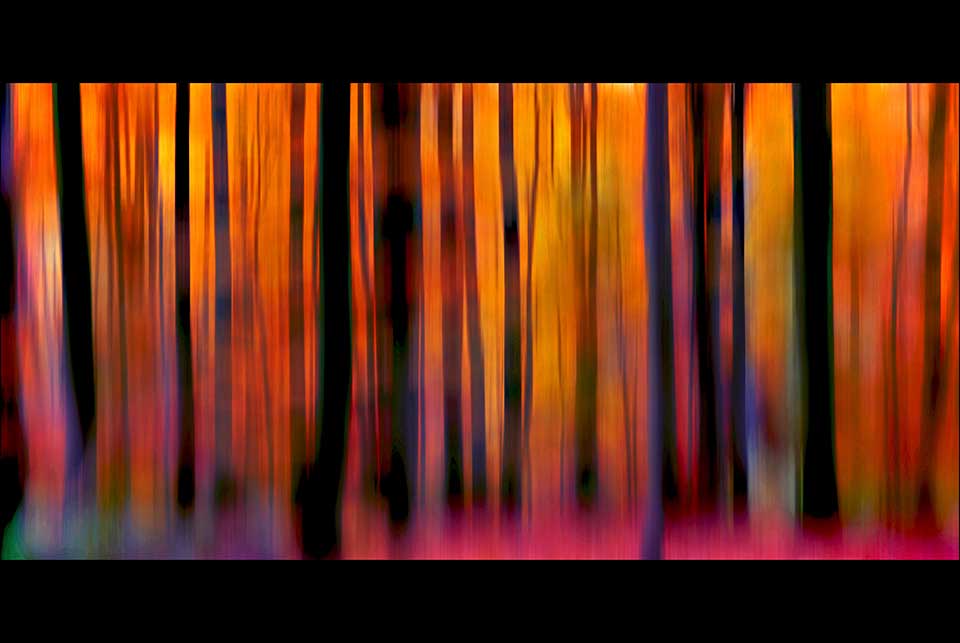

The Latin Bible lay open before him. He flipped around in it steadily. Ezekiel 21:3: Say to the forest of the Negev, Listen to the words of God. Thus said God: I am kindling a fire in you, a fire that will devour every tree, green or withered. Its blazing flame will never go out, and every face from north to south will be burned by it. Then all flesh will see that I, God, lit the fire, and it will never go out. . . .

Gjon Muzaka thought for a moment, “My body will burn and will never go out.”

Elsewhere, he read: God called forth a man clothed in linen, carrying with him a writer’s inkhorn and said, “Pass through the city of Jerusalem and place a mark on the foreheads of the men who sigh and lament the terrible things happening amongst them and me, God, God . . .” Such a guiding, comforting vision. . . . I should become a writer! thought Gjon Muzaka.

In another section, he read in Latin, Nil sub sole novum—nothing new under the sun.

He was stunned by this clear, cruel truth.

He took his swan feather, dipped it in his ancient inkwell, and wrote on a sheet of paper: Cuncta sub sole vana. Venite fili, audite, timorem domini docebo vos. Oculi domini supre iustos, et aures eius in preces eorum, vultus outem domini super facientes male, ut perdat te terra eos. Clamaverunt iusti, et dominus exaudivit eos, ex ominibus tribulationibus eorum liberavit eos.

As he wrote, Muzaka translated into Albanian: Everything under the sun is useless. Come, my sons, I will teach you to fear God. God turned his eyes toward honest men and his ears toward their prayers. The face of God also turns toward those who are evil—in order to annihilate them. Honest men raised their voices and God, from his distance, heard them and relieved them of their fears.

Prince Muzaka stopped writing.

He could see the panorama of Naples through his window. A long time had passed since he’d left Arbëria for Italy.

Arbëria now belonged to the Ottoman Empire.

His principalities, his residence in Berat Castle—all his memories were frozen, devastatingly preserved beneath the heavy and unthinkable cupola of occupation.

Every intimate thing seemed well beyond his reach. For many years he had lived comfortably in Naples—and yet his uneasiness grew.

Here, he was only a stage prince—not a real one. He was just a name—not a powerful man of the old world. He was an exotic, insignificant ghost—not at all vibrant, substantial, or imposing.

Here, he was only a stage prince—not a real one. He was just a name—not a powerful man of the old world.

Ach! he sighed, reciting to himself Ecclesiastes: Everything has its season, every occurrence under heaven has its time: a time to be born, a time to die, a time to plant and a time to reap, a time to kill and a time to heal, a time to tear down and a time to build up, a time to weep and a time to laugh, a time to dance and a time to mourn, a time to throw stones and a time to gather stones, a time to embrace and a time to oneself, a time to seek and a time to lose, a time to keep and a time to discard, a time to rend and a time to sew, a time to keep silent and a time to speak, a time to love and a time to hate, a time to make war and a time to make peace . . .

Muzaka shivered in his century-deep daydream.

He decided he would start writing in earnest. He would make a family chronicle, a genealogy—to put things in order, to describe his glories and defeats, to resurrect the lost histories.

He decided he would start writing in earnest. He would make a family chronicle, a genealogy—to put things in order, to describe his glories and defeats, to resurrect the lost histories.

He thought he was probably closer to dying than he realized. He should leave a will and testament to his sons, and the sons of his sons, so that the hallucinatory Arbëria inside him wouldn’t be lost—so that when his body died his Arbëria wouldn’t also vanish.

Inspired, he wrote in a torrent, assuredly and a bit deliriously. He recounted his ancestors, born near that mythical fount above which extinguished torches would begin to burn again, and burning torches would flicker out. He linked the Muzaka name with the Molossian Tribe; he recalled Great Pyrrhus of Epirus, and the Byzantine emperors who had conferred upon his ancestors impressive titles and family crests symbolically loaded with two-headed eagles and other allegories of imperial power.

He recounted marriages, the names of those who had died, as well as others who would come to die ritually and inevitably. He decided that his future offspring might one day return to Arbëria; thus, he mapped out the family properties with notable skill and in precise, concrete detail.

Oh, the properties, the properties!

He let his swan quill pause above the paper.

He reread what he’d written and felt like he’d just given birth; he was amazed and moved—but he was also enormously tired, exhausted. He could feel the speed of his approaching mortality being calculated behind a cloak of inevitability.

Oh vanity of vanities, everything is vanity, what has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done. Nil sub sole novum. Nothing new under the sun.

Prince Gjon Muzaka was almost solid—like a statue.

Thoughts, ideas, collide and, in doing so, destroy each other. He suddenly realized that his text was nothing special; millions before him had written it, and millions after him would write it again. Everything is transitory and passes; everything is a palimpsest, even a man and his property, his books and dreams, his pleas and nightmares, his wisdom and ignorance, his truths and lies. Even life and death are a palimpsest, a rolled-up palimpsest—since, it turns out, our visionary and dazed prince had unwittingly clarified the parable of the fount above which extinguished torches would begin to burn again, and burning torches would flicker out.

This mysterious fount was the future—was God.

Muzaka was a torch that had been burning and would soon be snuffed out by that alluring fount.

Perhaps for five centuries I’ll be an extinguished torch, locked in darkness, vanity, and nothingness. But then, maybe in some unknowable time, my torch will dip closer to that murderous fount and then, O God, will blindingly reignite with an astonishing, eternal glow.

Translation from the Albania

[i] Translator’s note: Gjon Muzaka was a fifteenth/sixteenth-century Arbërian nobleman—Arbëria being the medieval name for Albania—whose memoir Breve memoria de li discendenti de nostra casa Musachi is among the oldest extant books by an Albanian.

Editorial note: “The Testament of Gjon Muzaka” (2000) comes from Zeqo’s story collection Shitësit e kaosit (Sellers of chaos), published in Albania in 2010.