A Guide to Place: A Conversation with Ann Cummins

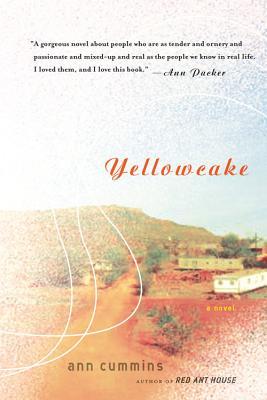

As I opened to the first page of Yellowcake, a novel chronicling the lives of uranium miners in Colorado and New Mexico, I was sitting in the entryway to my tent, looking out on Black Mesa, the highest point in Oklahoma and the first stop on my road trip through Colorado and New Mexico. I expected an accompaniment to my travels; what I received from Yellowcake was far more than that. Ann Cummins’s words led me to each of my destinations, introducing the various landscapes before I arrived. On my travels, I moved through Black Mesa, Boulder, Durango, Mesa Verde, the Million Dollar Highway, Farmington, Shiprock, Santa Fe, and, later, a flight to Florida. The ground I covered moving through the southwestern and southeastern United States reflected the landscape in Yellowcake. As I reached each destination, I was influenced and connected to the place, as if magically, imagining I saw the different characters from the novel at each stop. I felt I had truly entered the world of the book.

When I returned from my trip, I had the opportunity to interview Ann Cummins. Cummins spoke of her personal history growing up on a reservation in Shiprock, New Mexico, which led to the development of the diverse lives of her characters in Yellowcake. The Cummins family moved from Durango, Colorado, to the uranium-milling town of Shiprock, New Mexico, where Cummins attended high school. Unbeknownst to Cummins at the time, her experiences in Shiprock and her father’s career as a uranium miller influenced the landscape, characters, and plot of Yellowcake. [i]

When I returned from my trip, I had the opportunity to interview Ann Cummins. Cummins spoke of her personal history growing up on a reservation in Shiprock, New Mexico, which led to the development of the diverse lives of her characters in Yellowcake. The Cummins family moved from Durango, Colorado, to the uranium-milling town of Shiprock, New Mexico, where Cummins attended high school. Unbeknownst to Cummins at the time, her experiences in Shiprock and her father’s career as a uranium miller influenced the landscape, characters, and plot of Yellowcake. [i]

Cummins’s novel follows the lives of several characters on a Navajo reservation along with the health complications arising in the lives of older uranium miners. Since Cummins’s father was a uranium miller, she noted that he was influential in the development of one of the main characters, Ryland Mahoney. I asked Cummins about the life of her father’s work and how greatly this motivated her to write Yellowcake:

My father, the man, inspired me greatly. My father was very much a “right to work” individual, a man who felt obliged to provide for his family, pretty much a company man who stood by the company and industry that employed him. Understand that my father was from mining communities. His father and his uncles had worked in Durango’s mining industry in one capacity or another. When Durango’s skies were full of smoke from the smelter that smelted coal and other ores, his father got sick and eventually died of brown lung. When I started writing Yellowcake, I was mostly inspired to write about the next chapter in the life of mining communities. That was the uranium chapter.

Like most writers, Cummins writes from moments of meaning in her life but elucidated that she found liberation through fiction, as developing characters allows her to imagine the larger picture, exploring areas she was unable to in her own life. For Cummins, character development is just as important as emphasizing place:

Barry Lopez, in an interview years ago, talked about how he “conjured” stories by going to a specific place, closing his eyes, and asking, “Who are these people; what is this place?” That resonates with me. People—characters—draw me into fiction, but people come from places with histories, places with specific weather patterns, specific beauty, and terror in the landscape. I can’t enliven characters without considering how they’ve experienced the place of the story, how they’ve been shaped by a particular setting or geography in a particular time. So, for me, place is as important as character. They’re intertwined.

In Yellowcake, Cummins wrote the voices of at least five major characters in order to understand and synthesize an experience at its best. When I read Yellowcake, the “places with histories” spoke to me especially, as I did not previously know about the history of uranium mining underneath the lands I camped on. I felt anger toward the human toll of working with a dangerous substance like uranium and then saddened by the negative environmental repercussions. I imagined Cummins’s message in Yellowcake was to reveal these human and environmental atrocities that personally impacted her family and life. However, I was wrong in my assumptions.

When talking with Cummins about her choice to write fiction as opposed to an autobiography, Cummins replied that fiction expands experience; fiction allows a broader picture than could be presented through autobiography. I asked her if she was trying to convey a message through Yellowcake.

Messages are death knells for fiction, in my opinion. I write fiction because I get curious about something. My father was, for example, a curiosity for me. Why did he knuckle down and try to live the right life, and what was the right life to him? And where did it all fall apart? The uranium industry on the Colorado Plateau was also a curiosity to me. Writing Yellowcake helped me learn more about it—its history, the way it shaped my family’s life and the lives of other uranium mining families.

Cummins’s focus on the characters rather than the environmental, physical effects of uranium mining brought me to a realization of the importance of place and how it flows through and pushes forward those who inhabit it, and mostly the importance of storytelling. Yellowcake was an excellent host during my travels, guiding me lightly and leaving me with a story that stuck to my bones—a story I took home with me.

FOOTNOTES:

[i] Uranium millers work in the process by which materials are broken down and uranium is extracted through chemical leaching, yielding a dry concentrated power made up of natural uranium, referred to as “yellowcake.”