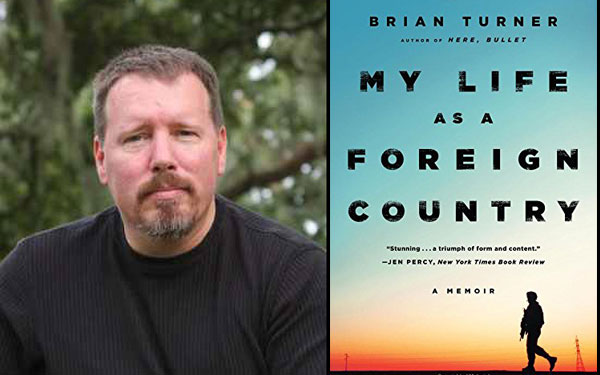

A Conversation with Brian Turner

Brian Turner is an American writer and the author of Here, Bullet. He served seven years in the US Army and was deployed to Bosnia-Herzegovina in 1999–2000 and later to Iraq in 2003. He has received an NEA Literature Fellowship in Poetry, the Amy Lowell Traveling Fellowship, and a fellowship from the Lannan Foundation. The following is adapted from our conversation at the recent Cork International Poetry Festival.

Sonnet Mondal: Brian, you belong to a family of army men who have served in almost all the major wars of the world—from World War I to Vietnam. Did your great-grandfather, grandfather, father, and uncle write poetry too? Was it war that brought out the poet in you, or was it poetry that helped you survive during your deployments?

Brian Turner: I’m not sure if my great-grandfather read poetry or wrote verse of his own, but I know my grandfather did, as did my uncle, and my father was a lover of literature his entire life. For my own part, I started writing poetry in my teenage years, nearly a decade before I joined the army, and I wrote because I was drawn to the music of the imagination and to the beauty of language itself. I also was a budding musician, a bass player in a rock band, and I thought perhaps learning verse might help me write stronger lyrics for the band. So, I’ve been a poet throughout many periods in my life—as a student, a machinist, a soldier, a teacher, and during many other experiences.

Mondal: From your poetry collection Here, Bullet, you turned to prose in My Life as a Foreign Country. Do you find prose more appealing than poetry?

Turner: I enjoy writing and reading both poetry and prose, but for different reasons. I think part of the reason I’m drawn to prose is that part of my process of thinking involves searching into tangents, the dirt paths that lead off of the main walkway of the mind, the side places that connect to the journey but are difficult to see from the main path.

Mondal: One of the most prominent World War I–era poets, Wilfred Owen, writes, “My subject is War, and the pity of War. The Poetry is in the pity.” Do you feel the same?

Turner: In terms of the poetry I’ve published so far (two volumes, with one written in Iraq as I served there and the other written a few years later in response to returning home), I think the landscape of my poems appears to many as the landscape of war, conflict, and what a soldier might carry home. That said, the subject of these collections isn’t war; the subject of these poems is love and loss.

The subject of these collections isn’t war; the subject of these poems is love and loss. Click to Tweet

Click to Tweet

Mondal: Your poetry is much like an uninterrupted conversation. It often happens that, when we pen things from memory, we tend to forget some of the issues or themes upon which we wanted to write. Sometimes those thoughts never return and pass into oblivion. Did you maintain a diary during your posting in Iraq and other countries? Or are your writings comprised of whatever you remember of those days? How popular was your poetry among your colleagues?

Turner: I did keep a journal throughout my time in Iraq, and the majority of the work I did was of a diary-like nature, with some diagrams of streets and neighborhoods penciled in, too. The poems in my first book arose from these observations—and I transferred them to a separate notebook and completed the book of poems while I was still in Iraq (except for two or three more poems that were written the month after we returned). I didn’t actually share the work with my colleagues while in Iraq. There are a variety of reasons why, but one of them was because it was a space for me to be Brian, and not Sergeant Turner. I needed a space to be the larger version of myself and not simply the role of my position in the squad.

Mondal: The style and diction of poetry differ widely from country to country. You are currently teaching at Sierra Nevada College. As a tutor of an MFA in creative writing, do you feel there are certain parameters every good poet should fulfill?

Turner: Each age must discover its own music, though that’s most often accomplished in conversation with the past, with the music that preceded it—even if only in an oblique way. I think this is true on an individual level, too. To make matters even more difficult . . . each poem also has its own needs and its own call for oxygen and light. We breathe our voices into the language, and we animate our poems with the all the surprise and delight available within the wide landscape of the imagination.

We breathe our voices into the language, and we animate our poems with the all the surprise and delight available within the wide landscape of the imagination.

As founding director of the MFA in creative writing at Sierra Nevada College, I’ve been honored to work with a wide range of writers over the years. We call them students, but in the larger arc of a life, these are writers, colleagues, human beings grappling with art and the imagination. In my program, they come from all walks of life, both nationally and internationally, with some joining us from China, France, Canada, Germany, and so on.

Mondal: The dividing line between life and death is less keenly felt in war-struck zones. Killings become as obvious as the cracking of eggs during breakfast. It seems as if poetry, however strong, is limited to a small community of poets. Do you feel poetry has a societal role to play? Where does your poetry stand in this regard?

Turner: The first part of this question is, I believe, far more complicated and messy, just as human beings are, and we’d need a great deal of time to explore those possibilities in responding to the complexities that take place in war zones. That said . . . poetry has many potential roles to play. Sometimes, the need is internal—and a poet explores his internal life through verse in order to better understand the soul, the antecedents that are at play in the construction of self, and more.

There is also a great need for poets to articulate what must be said—speaking truth to power, as it’s often described. Poets are often crushed when they attempt this, and they recognize how difficult the task can be—to speak artfully and memorably to a moment in a way that crystallizes that moment, a movement, an idea. There are many more roles, but these are a few.

Mondal: You have already experimented with fragmented prose in your latest book, My Life as a Foreign Country. Do you have plans to explore other genres of literature in the future? When will we get to read your next book?

Turner: I love this question. I’m currently working on a music project (check out www.roelvertov.com), and I’m collaborating with a composer on an opera. I’m hesitant to say it, but I’m also working on a large work of fiction.

My most important project, though, is to find a publishing house for my wife’s second collection of poems and to publish her work in great journals, literary sites, and more. Ilyse Kusnetz (1966–2016) was a poet, journalist, and teacher. Her first collection, Small Hours, was published in 2014 as the winner of the T. S. Eliot Prize for Poetry.

February 2017