A Deep Bow to Mombasa (and Sea Monsters): A Conversation with Khadija Abdalla Bajaber

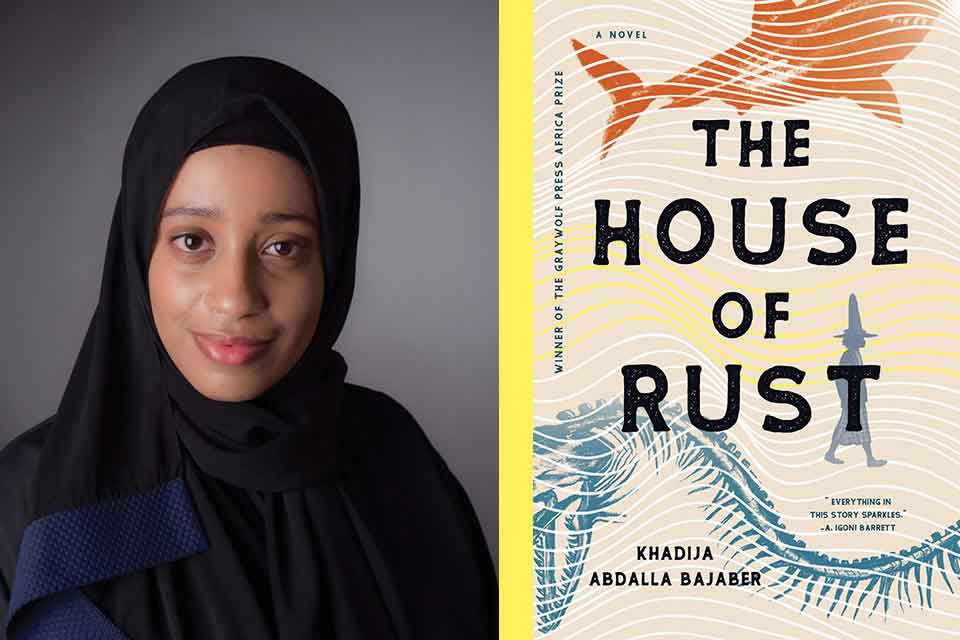

Khadija Abdalla Bajaber’s astonishing debut novel, The House of Rust, winner of the inaugural Graywolf Press Africa Prize, arrived in October as if on a magical wave, imbued with an assortment of creatures—human and animal, real and imagined—that populate the city of Mombasa and its surrounding waters. Aisha, fierce and adventurous, sets off on a boat made of bones in hopes of rescuing her fisherman father who has disappeared at sea. What she encounters on her search—and return home—will enthrall and amaze. “On the surface this is a limpid tale,” writes author A. Igoni Barrett, the prize’s judge, “but it is eddied and enriched by what lurks beneath the surface of both the sea and the prose. Everything in this story sparkles.” I spoke with Bajaber about Mombasa, sea monsters, and Aisha’s journey of self-discovery, among other things.

Anderson Tepper: Congratulations, Khadija. I’m curious about the story of your book’s path to publication. Did it change much since being awarded Graywolf’s Africa Prize in 2018?

Khadija Abdalla Bajaber: Thank you very much. Well, it definitely changed and grew. When I’d first finished working on the book, it ended at what is now actually the midpoint. I was quite happy with that ending at the time but was already beginning to rethink things. There were subplots I’d set up at the beginning that needed resolving. So then I started developing everything more; and toward the end, when everything was due, I ran off, took a few months to myself, and started writing madly. I added a sprinkle of this and that, some new characters, some new elements. My editor was very patient and good to me, bless him—it was chaos that he helped me order. But I’m so glad the story grew and I could talk things out with him, that I felt my ideas and vision were trusted and encouraged.

Tepper: Was this your first attempt at writing fiction? What were the particular challenges of working on a novel for you?

Bajaber: I’ve said before that writing this book was mostly quite simple. It was the organizing that was a little more difficult. But now I’m wondering if time and distance have blurred out the challenges past-me must have faced. I wrote a lot of fiction before. House of Rust is just the only one I finished at that time. I’m flighty when it comes to ideas; I always abandon a good one for a better one, and so on and so forth. I’m better now, of course. More dedicated. But back then? Miserable. I did manage two finished short stories in the past three years. People say the novel is hard, but trying to master the short story has been a trial.

People say the novel is hard, but trying to master the short story has been a trial.

Tepper: The House of Rust reminded me of some of my favorite writers, especially from East Africa—Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, Mia Couto, Nobel winner Abdulrazak Gurnah—but it is specifically rooted in Mombasa. In your acknowledgments, you describe it as “a city of wedding singers, wily merchants, mkokoteni pushers, grand matriarchs, dandy old men, cunning fishermen and quarrelsome crows—but, above all . . . a city of storytellers.” What was it about Mombasa that you wanted to capture in this book?

Bajaber: I’m not sure about that—those are some pretty big names! I’m most familiar with the work of the phenomenal Ms. Owuor. Dust is one of those books I read that I would go through the lines and be like, “This isn’t just a book, this isn’t just art . . . this is cinema.” Do you know how difficult it was to not read The Dragonfly Sea during the whole time I was writing?! Owuor’s got that great, wild love for the sea and is an empathetic and masterful writer. The Dragonfly Sea would have surely bewitched me. And to be bewitched would have run the risk of influencing my still-developing work.

Mombasa, as you say, is a city of storytellers, and I am but one of many. What I’ve written about this place is just a small piece of the tapestry. This book is not pretending to be the defining “Mombasa” story. I was saying I’m only one voice in a sea of many voices that should be heard.

And being a city of storytellers requires one to have kindness and warmth, but also cunning. People talk down a lot to Mombasa folk, and Coast folk in general. They praise our hospitality but forget that we have teeth too. We have intrigues of the likes that would bring those unschooled in the ways to tears. Here there’s mischief, there’s cleverness, there’s sarcasm and wit. I think I wanted to say, “There are things we know that you can never know.” I wanted to say, “Do not make light of us. Though we smile very well, it is not you who indulge us but we who indulge you.”

Tepper: While portraying a vast range of lives in Mombasa, your novel also provides a window into the Islamic Hadhrami culture. Tell me more about this community and how it’s been depicted, or neglected, in literature from the region.

Bajaber: I’m part of the diaspora that settled in Kenya, and unfortunately I don’t know enough Arabic to take advantage of the research on the matter. Most of my detail is gleaned from things I’ve personally observed and lived. I went to Yemen when I was a teenager, and it was a heartwarming experience. However, the culture here developed differently. The Hadharim are known for coming to countries, settling into communities, and adapting however they can. But we still maintain values that come from the old country—our traditions, our idea of what honor and hospitality is and such. The heart is open, but the heart of our heart is closed, private.

There’s very little literature. Everything I ever got my hands on has mostly been about communities in Yemen or the UK, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Somalia. There’s very little accessible information, and most of it is written by orientalists.

Regardless of where the Hadharim settled, as much as we keep our old ways, our traditions always mesh with the local traditions. The East African coast was subjected to Arabization by the Omani sovereigns, but the Arabs here were—what is the word? Swahilized? Any community that comes here ends up romanced and integrated by the strong, already-established Swahili culture. There was already a sharing of values and religion, already something in common. The Swahili culture is a poet culture, as is the Hadhrami culture. In some ways, I don’t know if any other two communities have ever suited each other better.

Tepper: At the heart of the novel is the character of Aisha, a “strange fiction of a girl” who has inherited her mother’s “half-feral heart” and her father’s tragic sense of “sea-longing.” Did Aisha’s tenacity surprise even you?

Bajaber: I wouldn’t say she surprised me; she did intrigue me, she did frustrate me—you’ve got this earnest girl who needs to find a way to finally come alive. I wanted her to be a bit bold, but always questioning, always looking inward, always doubtful. I wanted recklessness but also self-control, awareness.

All girls are fictions when we don’t have a hold of our lives, when we’re busy playing this part of “girl”—yes, even girls in the “Western world.” It’s not a condition specific to one community. The trap of that word is shaped differently wherever it is, but its trappings are felt. You’re always in a place where you have to embody the fiction until you figure out if it’s true or a lie, or a lie that you’ve willed into being the truth.

You’re always in a place where you have to embody the fiction until you figure out if it’s true or a lie, or a lie that you’ve willed into being the truth.

Tepper: Your prose has a remarkable rhythm all its own. How were you able to find a language—or combination of languages—that worked for this book?

Bajaber: Thank you, and what an interesting question! My Kiswahili is . . . “unreliable.” I learned it all by ear. But then sometimes—when the weather is right, when the social situation loosens the knot from my tongue—I can speak it well enough. It’s such a beautiful language: it’s got wittiness, color, slyness, rhythm. To hear it spoken by one well-versed, whether you’re talking to some degree-decked intellectual or the man selling you fruit, there’s poetry and rhythm.

Playing with poetry meant loosening and discarding any respect I may have had for English. So when I was writing, I wasn’t translating but going with my gut. What’s the most melodious, natural way I can give voice to these things? I can only half-capture the cadences and deliciousness of Kiswahili. I told myself I have to write like someone who knows the pleasure and sweetness of words that one is delighted to share. English isn’t unbreakable—you bend it, you assemble it how you like. Kiswahili is full of feeling, rhythm, music; so you carry over that dream into English without any of the rules.

English isn’t unbreakable—you bend it, you assemble it how you like.

Tepper: The House of Rust is alive with fantastical creatures—there’s a philosophizing cat, nattering crows, shark and snake sea demons. Are these figures from local folklore or your own imagination?

Bajaber: I made it all up, except for one or two instances. Not much is written, even if I had wanted to do research on documented monsters. We’re oral storytellers, but we also believe very much in the reality of such things. A myth is a dead thing, and our monsters are not dead things. So I was careful to not draw too much on any real thing; I even avoided learning too much about the living things. So I made most of the stuff up—drawing from culture, manners, and such—to give the monsters the way they speak and what they consider their priorities.

Tepper: Aisha’s independent spirit leads her away from her traditional path as a young bride and toward a quest for the mysterious “House of Rust.” What does this search mean for her?

Bajaber: It’s no sin to be traditional or a bride, but it’s a waste to go into anything passively. Know what you long for and move toward it! That’s what I wanted for all these characters. If it’s a path, traditional or untraditional, make sure you’re the one carving it and go marching properly, wholeheartedly.

Sometimes I think about Aisha, or dream of her, and I see what she’s doing now. She’s become independent of her creator: here she is walking through a market, fishing along some coast, running a beaded bracelet through her fingers in some strange place she’s never been to before. I wonder if she has arrived. Sometimes she has, sometimes she never does—but it’s her journey, the continuing journey, that I imagine. The “House of Rust” has been so real to me, it’s like I’m sure if I climb into a boat I’ll be able to feel my way there by instinct. When I think of her, I get some small dose of peace, some happiness, that she’s out there doing what she feels she ought to do.

Mombasa taught me hard lessons, but it also taught me that I am loved.

Tepper: Finally, I’m wondering whether The House of Rust will be published in Kenya and what the reaction might be. Judging from the book’s dedication, it sounds like you’ve had a complicated relationship with your home city: “For Mombasa, I thought you were trying to kill me. It has been a privilege, thank you.”

Bajaber: Jahazi Press is going to be publishing the book in Kenya. I’m quite happy about that. I am thankful for a global readership, if I should have one, but a love letter should reach the person it’s addressed to, shouldn’t it? I hope the people here like it; and even if they think the book is a whole lot of fanciful rubbish, I hope my sincerity is felt.

But, ah, that dedication. I wanted to dedicate it to my family and more, but we’re so many and I couldn’t name them all on one page. All my friends, my family, my neighbors, every facet of this society, these many, many communities—they’re Mombasa. I always felt tormented by home, as young people often do; but what tormented me was not knowing who I was. In accepting myself, I accepted everything. Mombasa wasn’t trying to kill me, I just thought it was. Mombasa taught me hard lessons, but it also taught me that I am loved. Accepting that love wasn’t easy; it still isn’t. So I wanted to acknowledge Mombasa. I wanted to say I’m not ashamed of Mombasa or myself. It’s been humbling, it’s been an honor, it’s been a war of sorts. It was a kind of deep bow, without shame, for a place that has been tough with me and so generous to me. I’m one of your daughters, I was saying. I won’t ever forget.

October 2021