Everything Ever After: A Conversation with Michael Cunningham

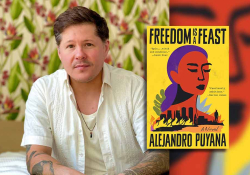

Courtesy of FS&G.

What happens after “ever after”? Michael Cunningham, the Pulitzer Prize–winning author of The Hours and A Home at the End of the World, answers that and other questions in his new collection of retellings, in which he reworks tales both famous and obscure from the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. A Wild Swan and Other Tales rhymes his text with the work of genius illustrator Yuko Shimizu; the pairing works as beautifully and as improbably as any authentic fairy tale romance—it is a disquieting match, in other words, and a perfect one: moody, threatening, but magical (click here to read the excerpt “Jacked”). I talked with Cunningham about his collaborative process, his personal history with the stories, and the secret lives of their protagonists.

Michael Cunningham: When I was a kid, when my parents would read me fairy tales, we’d get to happily ever after, and what happened then? So, this is eleven retellings that start from the end of the fairy tale and go to what happens when they get to the castle.

Michael Merriam: Who is the happiest fairy tale couple, after “happily ever after”?

MC: I did some happy ones and some tragic ones. “The Steadfast Tin Soldier” turns out happy.

MM: I’m glad to hear that. That one upset me when I was little.

MC: Yeah, it’s upsetting. I gave it a happy ending.

MM: Was there one that upset you?

MC: Oh god, yes. “The Little Match-Girl” really freaked me out.

MM: Growing up in the 1990s, it was all “Snow White as you’ve never seen her before,” you know, with a gun, or what have you. We had the reimagined versions, but the traditional versions were actually the uncommon ones, and seeing the reworked version was kind of a rare event.

MC: I’m older than you, but even I grew up with the Disney versions.

MM: Now, do you have a favorite collection of retellings?

MC: Angela Carter is amazing, as is the book of Anne Sexton’s poems called Transformations.

MM: So you don’t dislike the Disney films as strongly as some fairy tale aficionados do?

MC: Not as strongly, no. No. I saw Snow White when I was six, and I was completely enchanted by it, and it’s beautiful. Of course I understand how sanitized they are, though the early ones from the 1930s, like Snow White, are actually more macabre.

Of course I understand how sanitized the Disney versions are, though the early ones from the 1930s, like Snow White, are actually more macabre.

MM: Yeah, Snow White has a lot of ghoulish visual quotations from horror films in it. Sometimes I think the trademark Disney sanitization starts with Winnie the Pooh, the first one that has pretty much nothing macabre in it at all. Even Lady and the Tramp shows a dog going off to be euthanized; the films had plenty of dark elements in them.

MC: Yeah, Snow White has some scary shit in it. Even the cheesier ones like Sleeping Beauty have that. Maleficent is scary.

MM: Maleficent says “hell,” she talks about summoning all the powers—

MC: Right, of hell, you know? Not of “heck.”

MM: So what about “Cinderella”? What was that story like for you as a kid?

MC: It wasn’t one of my favorites; it didn’t get me the way it did some others. I don’t know why.

MM: When you started reading on your own, did you still read fairy tales and children’s literature?

MC: Yeah, I read all the time. I read Winnie the Pooh and a book called A Wrinkle in Time. That one was just so huge, and I read it over and over again. Madeline L’Engle. That was the one that really, really knocked me out.

MM: Is your new collection geared toward young readers?

MC: No, no-no-no. These are for adults. They are not for children. They’re sexual and dark, and it’s not only what happens after “happily ever after,” it’s “what was really going on here?” What is it about a prince who wants to carry off and marry a dead girl? What’s that about?

These retellings are sexual and dark, and it’s not only what happens after “happily ever after,” it’s “what was really going on here?” What is it about a prince who wants to carry off and marry a dead girl?

MM: Was it dark or suggestive elements that guided your choice of the stories you adapted?

MC: It’s the ones that most interested me, you know—they’re not chosen for any particular theme.

MM: What’s the one that surprised you the most, in terms of retelling, with where it took you?

MC: “Snow White,” and the whole necrophilia thing.

MM: To move on to this illustrated masterpiece you’ve got coming out, what intrigued you about A Wild Swan?

MC: It’s hard to say, isn’t it, why we, as children, love certain stories in particular. For me, there was something about princes transformed into swans, a princess compelled to make cloaks out of nettles, and most of all—this is probably obvious, from my version of the story—about one of the princes left with one arm and one swan wing. It just slayed me, when I was five.

MM: How did you connect with your amazing illustrator?

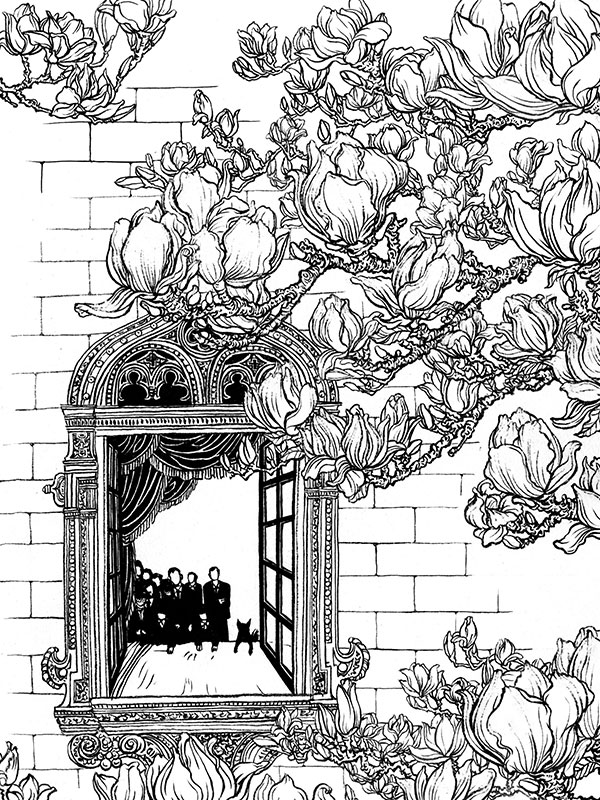

MC: I knew the kind of illustrations I wanted, knew they should be dark and perverse, but also magical and strangely beautiful. Lovely and a little nasty, if you know what I mean. That illustrator proved surprisingly difficult to find. There aren’t as many gifted freelance illustrators out there as you might think. . . . The great ones illustrate their own graphic novels and have no particular interest in illustrating work by someone else. So I just googled “Illustrator.” I found a few really interesting ones, but Yuko was by far my favorite. . . . The work I saw online was everything for which I’d hoped—ravishingly beautiful but also edgy, otherworldly, sexy, and strange.

I knew the kind of illustrations I wanted, knew they should be dark and perverse, but also magical and strangely beautiful.

MM: Can you talk a little bit about the way you worked together?

MC: After Yuko had read the entire collection, she and I met with Rodrigo Corral, the brilliant art director at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. I told Yuko I considered this a collaboration, albeit one in which half—the text—had been produced already. But I told her that, given the text, I wanted her simply to produce whatever images she liked, that I wanted to issue no instructions, or even to make suggestions. She was very happy about that. It seems that kind of carte blanche is rare for an illustrator (who knew?).

For most of the stories she made several different rough sketches, and she, Rodrigo, and I agreed on our favorites, though I always insisted that Yuko would have the deciding vote. Fortunately, we three agreed on all our favorites. She then went ahead and produced the final illustrations. They’re simply pen and ink. They’re drawings, in the most traditional sense of the term.

It was Yuko who suggested the drop caps—that is, the illustrated first letters that open each story. Which is, of course, a measure of her enthusiasm, generosity, and general fabulousness. Oh, she designed the cover as well, with the same free rein.

August 2015