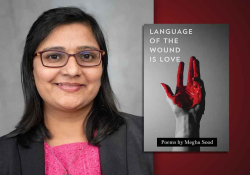

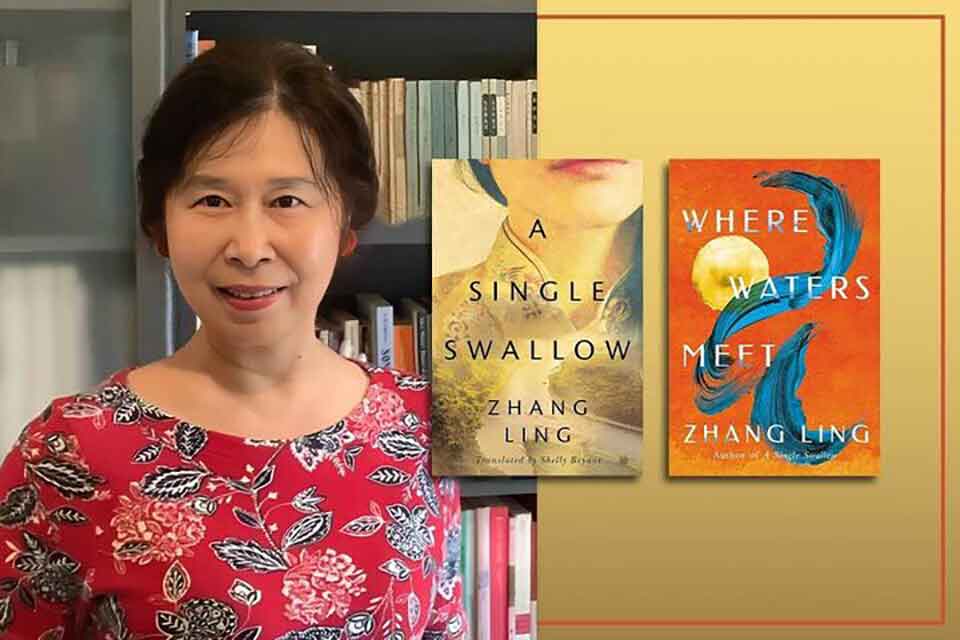

War, Trauma, and Human Courage: A Conversation with Zhang Ling

Zhang Ling is the author of ten novels, including A Single Swallow (trans. Shelly Bryant) and Where Waters Meet, the first two novels in her Children of War trilogy. Focusing on war, trauma, and human courage, her work fights against collective oblivion and fosters empathy and understanding.

Zhang Ling is the author of ten novels, including A Single Swallow (trans. Shelly Bryant) and Where Waters Meet, the first two novels in her Children of War trilogy. Focusing on war, trauma, and human courage, her work fights against collective oblivion and fosters empathy and understanding.

Yan Lu: The trilogy Children of War is your first focused attempt at the subject of war. You have completed the first and second novels of the series, A Single Swallow and Where Waters Meet, both revealing the enduring impact or what you call the “spillover” of war on ordinary people that lasts beyond wartime and generations. When did you begin to plan out the trilogy, and what inspired you to embark on this subject?

Zhang Ling: For the past decade, I have been planning to write a trilogy called Children of War. As the first two parts of the trilogy—i.e., A Single Swallow and Where Waters Meet—have been completed and published, I am now in the research stage for the third and final part. These three books have completely independent storylines, and none of the characters are spin-offs from previous books. However, they share a common theme of war, trauma, and human courage.

Before becoming a full-time writer, I worked as a clinical audiologist for seventeen years. At different points in my audiologist career, I saw veterans from World War I, World War II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the more recent wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East. I also had the opportunity to treat refugees from war-torn and disaster-stricken countries. I saw with my own eyes how these people struggle to come to terms with the impacts of their traumatic experiences, which have, in various ways, affected their relationship with the world as well as themselves. Their survival stories have inspired me greatly, motivating me to explore the subject of war, trauma, and healing.

Since I spent my most important and formative years in China, a country known for its long history of wars and social turmoil, I can easily relate what I have observed in the clinic to the events that took place during the early part of my life. In other words, my childhood memories in China and my adult working experience in Canada have both played a role in the creation process of this trilogy.

My childhood memories in China and my adult working experience in Canada have both played a role in the creation process of this trilogy.

Lu: The war of resistance against Japan in China, as part of World War II, is an important backdrop against which A Single Swallow and Where Waters Meet are set. You have uncovered many overlooked facts and stories from that period, which may not make their way into official history. Could you please share your research process and your effort to fight against oblivion, “the deadliest foe of humanity” in your eyes?

Zhang: Spanning decades and continents, A Single Swallow and Where Waters Meet tell a story about a period of modern Chinese history known for constant wars and social turmoil. A novel of this nature requires extensive library research and field trips for background knowledge. The research reading enables me to extract crucial details such as dates, locations, and timelines of historical events, which serve as the foundation of the narration. The field trips, on the other hand, take me deep into the memories of those who witnessed or have knowledge of the events. Visiting a site that has experienced a tragic event can evoke unexpected emotions, even if there are no survivors present. An abandoned house, a tree, a hill, a tombstone, or even a distant cousin can uncover stories that may not be found in any government documents or archive materials. These journeys have filled me with inspiration, leading to the eventual inception of the narrative.

The past century has seen an increase in global conflicts and wars. However, as time passes, we tend to forget about past destructive events, especially when new ones take over the headlines. While war and trauma are easily defined, their lingering effects, the “spillover” as I call them in Where Waters Meet, are more elusive, less clear-cut, and often conveniently overlooked. The trajectory of my characters’ lives, as portrayed in A Single Swallow and Where Waters Meet, is just an example of such spillover. As a writer, I believe it is crucial to remind people of truths and memories that may not be pleasant but need to be remembered so that history will not repeat itself as frequently as we have sadly observed. I hope that my writing can contribute to the global effort against collective oblivion.

I hope that my writing can contribute to the global effort against collective oblivion.

Lu: At the center of both novels are women: Ah Yan in A Single Swallow and Rain and her daughter Phoenix in Where Waters Meet. You describe women in your writing as “survivors.” With waterlike resilience, they struggle to “outlive” the trauma, adversity, and loss that life has to offer. How did you develop these fictional characters?

Zhang: Throughout my childhood and youth, I was surrounded by strong women. My maternal grandmother gave birth to eleven children (in addition to a few miscarriages) through wars and incessant social turmoil. The fact that ten survived to adulthood was nothing short of a miracle, as the infant mortality rate was very high in those days. With unbelievable courage, tenacity, and a great deal of common sense, my grandma kept this huge family afloat amidst all sorts of social unrest and economic hardship. My mother and her siblings, boys and girls alike, all received a good education for the time.

Ever since being a toddler, I’ve heard the remarkable survival stories of the women in my mother’s family. Rain in Where Waters Meet and Ah Yan in A Single Swallow had their roots deep in my heart. They just needed to wait for the right moment to sprout their first leaf on paper. While my perception of female resilience and strength is shaped by my close ties with these women in my family, my working experience as a clinical audiologist adds depth and dimension to my understanding of the destructive power that war has brought to people, especially women and children.

Lu: Where Waters Meet is included in the booklist of Tolerance and Understanding compiled by World Literature Today for the 2023 International Day for Tolerance. This theme is also woven into A Single Swallow. As a writer across cultures, how do you explore themes like tolerance, understanding, compassion, and forgiveness, which extend beyond national boundaries?

Zhang: I strive to write truthfully about my memories and the impressions they have left on me. It can be challenging for a writer from a transnational background to relate culture-specific issues to a wider audience. However, there are techniques that can be employed to dissect such chunks of information so that unfamiliar readers can understand them more easily. A good example in fiction writing would be to incorporate such knowledge as seamlessly as possible into the body of the narrative instead of inserting copious footnotes that distract and impede. While it can be difficult to execute, it is achievable with care and conscious effort.

We are going through a difficult time facing unparalleled challenges. The pandemic has profoundly altered many aspects of our lives, bringing loss so close to our door and fostering distrust and tension among peoples and nations. At a time like this, an in-depth examination of the issues related to trauma, compassion, tolerance, and healing is not only relevant but also pressing. The only way for an author to effect positive change is through genuine and powerful writing. Honesty is the fastest route by which a writer can reach the mind of a reader, regardless of his/her cultural background.

The only way for an author to effect positive change is through genuine and powerful writing.

While trauma and suffering might assume a multitude of forms such as war, natural and man-made disasters, a broken marriage, or a derailed emotional life, they are fundamentally common human experiences that bind more than divide us. As a part of humanity, we don’t suffer alone. Our feelings and emotions, when truthfully expressed, are shared by many despite cultural and linguistic differences. Instead of trying to “win over” readers from different backgrounds, I attempt to focus on telling stories that convey truth and soul. My greatest desire is to become a storyteller who cultivates empathy and understanding toward the universal human condition while embracing my unique cultural roots.

Lu: You have been experimenting with new narrative forms to present your stories. In A Single Swallow, Ah Yan’s story unfolds, in the absence of her own voice, through the memories of three men’s ghosts. Where Waters Meet embeds Rain’s story within the correspondence between Phoenix and her Canadian husband as fragmented manuscripts. How did you choose these unconventional forms, and what experience would you like them to provide to readers?

Zhang: I believe that an author's choice of narrative form should serve the content and essence of their story. In A Single Swallow, the story of Ah Yan is told from the perspective of three male characters. The absence of Ah Yan’s voice, which has sparked feminist discussions, is intended to adhere to the story’s historical context. This novel is set in the early 1940s in a poor and isolated village in southern China. During that time, women were typically uneducated, housebound, and financially dependent. The dominant practice in rural areas was the rule of three stages of obedience, which meant that a woman should obey her father when she was young, her husband when she was married, and her sons when she was old.

Ah Yan’s silence reflects the social environment she is placed in. Her general demeanor may give the impression that she is compliant with the patriarchal rules of society, but in reality, she constantly engages in an active role that nurtures, comforts, mends, and heals. Her actions, as revealed in the vivid memories of the three men who have all loved her, each in his unique way, speak louder than her suppressed voice.

In Where Waters Meet, the story is presented in the form of a series of emails and fragments of a memoir manuscript arranged in a nonlinear fashion. This narrative form is primarily devised to connect the story of George and Phoenix, who represent present-day life in Canada, with the memories of Rain’s life across seven decades in China. A secondary purpose of employing such a device is to create and maintain suspense around the dark family secret that propels the story forward until the end. A novel spanning different continents and multiple decades can easily fall into disjointed individual anecdotes lacking organic connections. It is a daunting task to weave together the past and present and the Western and Eastern perspectives in a unified narrative. Hopefully, the literary form chosen for Where Waters Meet helps to establish inherent links between the individual events and to knead disparate elements into a cohesive whole.

It is a daunting task to weave together the past and present and the Western and Eastern perspectives in a unified narrative.

Lu: You consider depriving one’s use of the mother tongue as an invisible trauma brought about by the war. You have been fortunate to write in your native language of Chinese for more than two decades. What drove you to step out of your comfort zone and write your tenth novel, Where Waters Meet, in English? How does writing in a nonnative language shape your literary perspective and practice? What language do you plan to use in the third novel of the trilogy?

Zhang: I have worked diligently over the last two decades on numerous writing projects, producing nine novels and several collections of novellas and short stories in Chinese, the language I was born into and grew up with. Where Waters Meet (2023), my tenth novel, holds a special place in my heart as it is my first endeavor to write in English. The decision to switch languages was made for complex reasons, one of which, in retrospect, was my attempt to reach a broader audience. I wanted to share with them the events that are specific to modern Chinese history while also being a part of the universal human experience. The outbreak of Covid-19 and the associated international travel ban also played a role in this decision as I lost contact with the Chinese literary world for three years.

A language is not just a collection of words and a set of grammatical, phonetical, and syntactical rules; it also carries with it rich cultural, historical, and social implications particular to the group of people who use it. When we switch from one language to another, we become aware of, to various degrees, these implications as an inherent part of the language we choose. A different language brings in a new sense of rhythm, contextual associations, and musicality, which excites and rejuvenates me as a writer. When I am experimenting with a language I’ve always used only for practical purposes, I feel restricted and liberated at the same time. New images, metaphors, and associations come without warning, forming a new fabric of writing, weird at first glance, then becoming titillatingly alluring once my eyes have warmed to it.

A different language brings in a new sense of rhythm, contextual associations, and musicality, which excites and rejuvenates me as a writer.

Writing in two languages gives us an extra eye to perceive ourselves as well as the world around us. This third eye helps us discover the differences as well as the overlapping areas between the two languages, which gives life to unforeseen inspirations for cross-cultural thinking. When we start to explore these areas, we oftentimes find unexpected pathways to the depths of human minds. One’s first language gives one a sense of belonging and rootedness, which unfortunately gets lost in a second language. In a second language, one feels a little drifty and uncertain. However, this sense of uncertainty and rootlessness might foster a rekindled motivation for adventure and risk-taking.

I am currently researching the final part of the trilogy and have not yet decided which language to use.

Lu: Thank you for sharing your thoughts, Zhang Ling. I look forward to the final part of the trilogy.