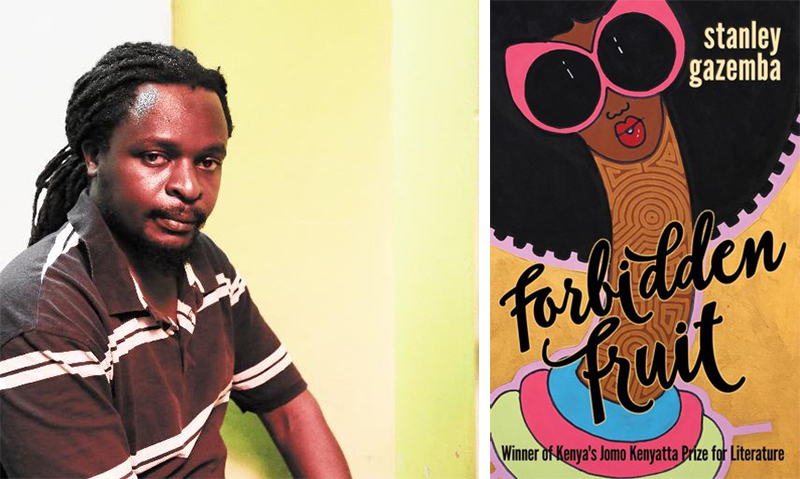

Humble Beginnings Make Solid Roots: A Conversation with Stanley Gazemba

Stanley Gazemba was working as a gardener when his first book, The Stone Hills of Maragoli, was published and won the 2003 Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature, Kenya’s top literary prize. And the Nairobi author hasn’t stopped there. He has gone on to write several novels and children’s books. The Mantle published his award-winning novel, retitled Forbidden Fruit, in June. In this interview, Gazemba gives insight on his literary journey, his writing process, and his own reading list.

Anna Hernandez: You’ve mentioned in previous interviews that you began writing at a young age; what were those stories about, and did they influence your writing later on in life?

Stanley Gazemba: I started out imitating other writers that I was reading in primary school. I was around eleven years old. Some of the popular titles in school then were the Hardy Boys series and the Moses series by Barbara Kimenye (Oxford University Press). We were especially influenced by Barbara Kimenye’s books because the setting was a boarding school in Uganda, and since we were also in a Catholic boarding school, we could identify with the misadventures in the stories.

I decided to create my own series that was largely influenced by these books. So I took some of my school notebooks and started writing. I was also a fairly good artist, and I would do the illustrations in pencil in the ruled notebooks exactly where I wanted them to appear when the book went to print. Most of my early characters were boys in tricky situations that they needed to navigate out of. They were either sleuthing around, playing hide-and-seek with dangerous criminals, or engaged in some mischief or other.

Of course, I had no idea how manuscripts were prepared back then, leave alone the steps a book goes through from manuscript to print! I didn’t know that I needed to type out the manuscripts first and that illustrations are prepared separately on plain paper using special pens!

Anyway, when I got to high school at thirteen, I gathered courage enough to send off my first of these manuscripts to a publisher (Oxford University Press). The editor was kind enough to write back to me. I remember the excitement when I received the stiff, white official-looking letter in the mail. I could hardly wait to tear it open. So I was finally going to become a writer!

Of course, it was a carefully crafted rejection letter telling me I had the flair for storytelling, but I needed to do ABCD in order to write a publishable story. I guess the editor came short of saying he could detect I was plagiarizing other writers, and that I needed to be more original! Nonetheless, that didn’t stop me showing it around, and soon all the boys in the schoolyard were calling me an author!

Anyway, as I continued improving my craft, I started developing a style of my own and generally learning the ropes, mostly by observing carefully how other writers used their words and how they constructed their stories.

Hernandez: When you write, what is your process? Do you have the story completely planned out from start to finish, or is it a more organic method?

Gazemba: Back in primary and high school our English teachers used to instruct us to approach our English composition the way an engineer would a structure they were putting up. They told us to draft the ideas that would go into the beginning, then the main body and the ending on a separate sheet of paper before embarking on the actual writing. In later, more advanced writing workshops I heard the idea that a good piece of writing has to be constructed around three points, just like the sturdiest structures, and that it has to taper upward to a point at its apex like a pyramid. That way it will be unshakeable.

I don’t have an argument against both approaches to the craft of writing. My only problem with them is that they turn writing from a craft to a science. They turn the writer, an artist, into an engineer. And we know that engineers only work with definite forms; squares, circles, ovals, triangles, and so on, and that in their thinking points are linked by straight lines. This is what I have a problem with as a writer.

If I were to build my pyramid, I would first identify the three points at the base and then apex. Having done that, I would find my own way of taking the structure up, twisting it into any imaginable shape possible without ever using a straight line. The only thing I would be conscious of is to maintain the center of gravity to keep it from toppling over. This is my best approach to the craft of writing.

A good writer needs to first of all master all the rules just to help him understand why they were made in the first place and then set out to bend as many of them as he can in the course of writing to make them suit his needs.

During the initial years of my writing, I used to draft out my stories in a separate notebook, clearly detailing what every chapter would contain. Thereafter I would embark on the actual writing. It was a very tiring approach, I guess mostly because I already knew where the story was headed, and I often found myself struggling with it. It was like trying to take an evening stroll in a straitjacket.

Then one day I just said to myself, why not toss out the rule book and let the story go wherever it wants to go? And that is just what I did. I dropped the notebook and just sat down and wrote. Of course, I already had a vague idea where the story was headed, but the point was that I was not going to stick to any predetermined path. That is when I discovered the joy in writing!

Of course, this approach is not guaranteed to beat the block—it will always still spring up now and then. But then the outcome is always much more pleasant and natural. I would recommend that writers who are starting out in their career try it. The idea is you first mull over the story idea in your head, thinking about the plot, the setting, the characters, and all that, writing down as few notes as possible, and then when you feel the story is abuzz in your head you just sit down and write. I think it is easier to discover your own individual style this way than if you go by the rule book.

Personally, I only sit down to write when the genie of the story has possessed me, and, trust me, when she gets a good grip on me, I won’t stop until the last dot.

I’ve heard other writers speaking of disciplining themselves to write, say, a certain number of pages a day, and even going as far as assigning a specific time of the day for it. I think this is a very dumb approach. You are a writer, not some machine churning out copies at timed intervals! Personally, I only sit down to write when the genie of the story has possessed me, and, trust me, when she gets a good grip on me, I won’t stop until the last dot. The golden rule: start out with a vague idea of what you want it to be, but for God’s sake, let the story dictate where it wants to go! I believe it is the best way to come up with text that sings on the pages.

Hernandez: Do you feel you have a universal underlying message or theme in all your works?

Gazemba: It is difficult to give a direct or general answer to this question because every book is unique in its own way. I think the answer largely depends on how the reader reacts to a specific book, and people’s perceptions are varied, largely depending on the person’s cultural background and their levels of exposure.

There are books that might appeal to a reader from equatorial Africa but which might seem alien to a North African, for instance. There are also books that might appeal to an African but seem alien to a European, and so on.

Still, there are themes in my books that I believe cut across cultures, things that any reader will react to from the universal human point of view. I have in mind things like vengeance, jealousy, dishonesty, oppression, ambition, love, and so on that are present in any country, be it in the so-called First or Third World.

However, I am not blind to the fact that there are numerous elements in my work that can only be understood or appreciated by people who have either lived in or were born in Africa. For instance, when I write about a Nairobi slum, I am certain someone in Europe or America who has never been to Nairobi would imagine the projects where the poor in their cities live. The same applies to a village in western Kenya.

Hernandez: Do you have a 2017 reading list (what you’ve read and what’s on the waiting list)?

Gazemba: It is a strange list because it is a mix of both new writing and classics. I am also that weird reader who will read two or three books at a time, sometimes abandoning a book for another and coming round to it later! For instance, it took me close to a year to finish Gabriel García Márquez’s classic A Hundred Years of Solitude, mostly because of his dense writing style—meaning in between I was reading dozens of other books! Anyway, I will try and list those that I have finished this year: Obinna Udenwe’s Satans and Shaitans, Ayi Kwei Armah’s Why Are We Wo Blest?, Mark Bowden’s Black Hawk Down, Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary, Ayi Kwei Armah’s Two Thousand Seasons, George Eliot’s Silas Marner, and Kwani?’s Majuu edition. Those are the ones I remember off-head.

There is a curious book on this list, too: Vikram Seth’s An Equal Music. I was given this book as a gift by Professor Shaul Bassi of Ca’ Foscari University in Venice when he visited me in 2012. I put off reading this book for a very long time because I thought it was about classical music, and classical music is hardly my cup of tea. Late last year, Prof. Bassi contacted me and said he was keen on having me in Venice in April this year to attend the Incroci di Civiltà Festival, which Vikram Seth would also be attending. Out of curiosity I dusted off Seth’s book and started reading. I never put down that book. It turned out to be the finest book I had ever read on love and music! Brought to mind that old adage about never judging a book by its cover! In the meantime, I am slogging in my stop-start fashion through John Reader’s Africa: A Biography of the Continent, Teju Cole’s Open City, Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment, and a handful of other books. I am also hoping to get my hands on Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s Kintu soon.

August 2017

Stanley Gazemba is an award-winning author from Nairobi, Kenya, who was once a gardener. His employer, American Susan Linnee, the East Africa bureau chief for the Associated Press at the time, gave him his first typewriter, which enabled him to get his award-winning novel published. Since then he has written several books and has also written stories and articles for international publications, including the New York Times. He currently lives in Nairobi and is an editor at Ketebul Music, where he recently edited and contributed to the latest publication, Shades of Benga: The Story of Popular Music in Kenya: 1946–2016.