The Many Worlds of Anna May Wong: A Conversation with Katie Gee Salisbury

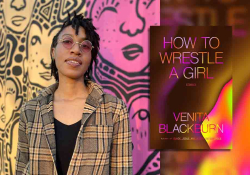

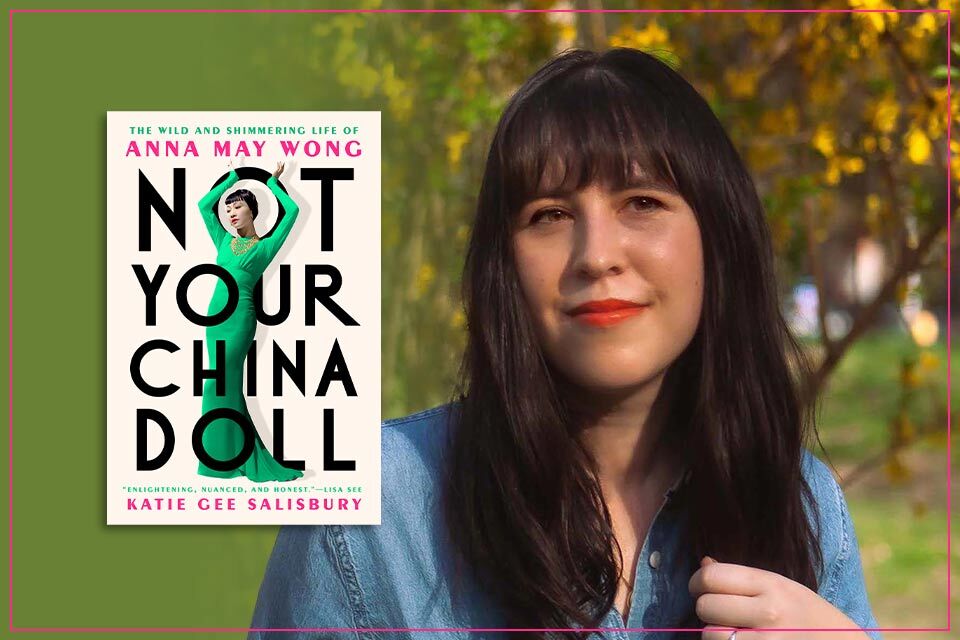

Katie Gee Salisbury first came across Anna May Wong when she was doing a college internship and found an old black-and-white photo of the starlet from almost a century earlier. This image would forever stay in Salisbury’s mind and would serve as inspiration for her new, definitive biography, Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong (forthcoming from Dutton/Random House on March 12). Although Wong was American as apple pie, she was never appreciated or celebrated in the United States in the ways that white actors of the same or lesser status enjoyed. In the 1920s Wong moved abroad and became a star in Europe. The following decade, she made a life-changing trip to China, Hong Kong, Japan, and the Philippines. In doing so, Wong became a household name in places few others have managed before or since. It’s in this light—of Anna May Wong’s worldwide appeal—that I discussed Wong with Salisbury over email.

Katie Gee Salisbury first came across Anna May Wong when she was doing a college internship and found an old black-and-white photo of the starlet from almost a century earlier. This image would forever stay in Salisbury’s mind and would serve as inspiration for her new, definitive biography, Not Your China Doll: The Wild and Shimmering Life of Anna May Wong (forthcoming from Dutton/Random House on March 12). Although Wong was American as apple pie, she was never appreciated or celebrated in the United States in the ways that white actors of the same or lesser status enjoyed. In the 1920s Wong moved abroad and became a star in Europe. The following decade, she made a life-changing trip to China, Hong Kong, Japan, and the Philippines. In doing so, Wong became a household name in places few others have managed before or since. It’s in this light—of Anna May Wong’s worldwide appeal—that I discussed Wong with Salisbury over email.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: Thank you for taking time out from your book launch preparation to discuss Anna May Wong’s life and work overseas. Anna May made an enormous change by moving to Europe when she felt that Hollywood wasn’t able to accept her in the roles she deserved. And it wasn’t to an English-speaking place, but Berlin! Can you talk a little about why she made this decision, why Berlin, and the direction you think her life may have gone if she hadn’t taken this leap in the 1920s?

Katie Gee Salisbury: Anna May Wong was only twenty-three when she set sail for the great unknown in Europe. The furthest she had been from home up until that point was Canada and a day trip across the border into Mexico. It was a big decision for a young woman like her to make, and as she said in her own words, many advised her against leaving Hollywood. The assumption was that she’d come back having been completely forgotten. She was willing to try her luck in Europe mostly because she was so fed up with Hollywood’s racism. Studios wouldn’t cast her in leading roles or even in anything with significant screen time, yet they often gave her top billing with the other stars because they knew her name would bring people in. Anna May knew she was getting a raw deal.

She was willing to try her luck in Europe mostly because she was so fed up with Hollywood’s racism.

At the same time, she had been circulating socially with more sophisticated types—artists, writers, and the British and German expats who now found themselves working in Hollywood. One of her lovers, the British cinematographer Charles Rosher, had just returned from a yearlong stint in Germany studying Weimar cinema techniques. He likely told Anna May of the incredible films they were making there. That, coupled with her meeting Karl Vollmöller, a German screenwriter and playwright who wrote a treatment specifically for her to play, likely convinced her of the path forward. UFA, Germany’s premier film studio, extended a contract and was ready to roll out the red carpet for her—they wanted to make her a star. How could she say no to that?

Honestly, if she hadn’t taken that chance in 1928 and sailed to Berlin—a place she’d never been, where she didn’t speak the language—her career would have been totally different. I’m not sure we’d even be here talking about her today!

Blumberg-Kason: There are so many what-ifs, but that one is especially chilling. Thank goodness she took that chance. Speaking of Berlin, as well as London, Shanghai, Beijing, Hong Kong, and more, did it seem daunting at first to cover her in all of those places? Can you talk about the research trips you took and if you found that the pandemic kept you from traveling to certain places? Do you think you would have conducted your research any differently if we’d been in “normal” times?

Salisbury: Daunting is the word! When I first started poking around in the archives a decade ago, I was still a newbie at research and had a lot of trouble even getting the correct microfilm rolls at the New York Public Library. It doesn’t seem that long ago, but most materials were still analog. You couldn’t find them online and could only access them in person.

Had things gone differently in 2020 when I sold the book, I likely would have planned research trips to various libraries in Europe and elsewhere right away. But the pandemic made the research process much simpler in a sense. Because I couldn’t go anywhere, I had to start by looking into resources I could access from my laptop at home. Luckily, a massive number of resources had been digitized by then. My go-tos were Newspapers.com, the British Newspaper Archive, the Media History Digital Library, which is a fantastic source for movie magazines, and I even found publications through French and German online archives. I’m proficient enough at reading in French, which helped me quite a bit, and I have a German cousin who gamely helped out with the German-language research. Once things normalized again, I was able to make research trips in person to some of the major Hollywood archives in Los Angeles, including the Academy’s Margaret Herrick Library, and to BFI in London so that I could watch some of Anna May’s rare European films.

The pandemic made the research process much simpler: because I couldn’t go anywhere, I had to start by looking into resources I could access from my laptop at home.

For her 1936 trip to China, I was able to track down a number of Chinese-language publications in the Paul Fonoroff Collection at UC Berkeley. Despite four years of Chinese-language instruction, I’m still not literate. I also studied simplified characters, and these 1930s movie magazines were all written in traditional characters. How would I even know which articles to look at and scan for translation? My workaround was this: I knew the characters for Anna May Wong’s Chinese name, 黄柳霜, so I scoured each publication looking for her name. When I found it, I scanned as much as I could and later had the articles translated. It was like playing Where’s Waldo but with much higher stakes!

Blumberg-Kason: I love those 1930s Shanghai movie magazines! I feel like all roads lead to Shanghai these days, and I’ll forever be grateful to you for reaching out to me after I wrote an article about Anna May’s friendship with the Shanghai salon hostess Bernardine Szold Fritz. The two became close in Shanghai, but Anna May traveled to more than just Shanghai in 1936. Did you get a sense of which part of China she enjoyed the most on that trip? She went to Shanghai, her ancestral hometown of Toisan, Beijing, and I think Tianjin. Did I miss any?

Salisbury: Goodness, I’m the one who should be so grateful to you! Your biography of Bernardine Szold Fritz shed so much new light on Anna May’s friendships and her time in China, including never-before-seen photos of her exploring the Chinese countryside and talking to the laobaixing (common folk).

Anna May Wong stayed in China for about ten months and did a grand tour of the country along the coasts. Along with the cities you mentioned, she made stops in Macao, Nanjing, Hangzhou, Suzhou, Qufu (the birthplace of Confucius), and likely several other smaller cities in the north. She also took a short trip to the Philippines when she had to escape an angry press pool in Hong Kong.

During her travels in China, she loved Beijing (or Peiping as it was then called) best, probably because it lived up to the stories she had grown up hearing about the motherland. In Beijing, she was able to live in a traditional Chinese home with a courtyard and garden, and she made friends with many of the locals and expats who lived nearby. The rhythm of life was slower there than in Shanghai, where she first disembarked and could barely get a good night’s rest for all the parties being thrown in her honor.

Anna May also held a deep appreciation for China’s history and culture. In Beijing, she could spend her days visiting the Peking opera school where young children trained in the ancient theatrical art, strolling the grounds of the Summer Palace, or gazing at the Temple of Heaven on a moonlit evening. She likely also busied herself by buying up antiques—one of her favorite pastimes. In fact, she ended up sailing home with several Peking opera headdresses and costumes.

Blumberg-Kason: And georgette, a term for crepe silk that I learned when reading about Anna May and Bernardine’s friendship!

I want to switch gears a bit and discuss another city since our original connection was a Hong Kong one. Your aunt, the writer Alison Singh Gee, and I connected after we had both lived in Hong Kong in the 1990s and wrote books set there. So it seems only fitting that you and I would eventually become friends! I was excited to see that Anna May spent time visiting her sister in Hong Kong when she was on her grand trip to Asia in 1936. Hong Kong back then must have seemed like a small town compared to the vibrant Shanghai of the 1930s. Can you talk a little about your research of Anna May’s time in Hong Kong? Was it difficult to learn about short visits there almost a hundred years earlier?

Salisbury: Most of what I learned about Anna May’s time in Hong Kong comes from local newspapers in both English and Chinese. It was interesting to see how her arrival there was written about differently. Either the English-language reporters didn’t pick up on some of the tensions between Hong Kongers and Anna May, or they chose to gloss over them in favor of a more positive portrayal. The Chinese papers, however, often criticized Anna May’s appearance, her wardrobe, her general demeanor, etc. A lot of what they said was quite insulting.

One article in particular still puzzles me—I had it translated into English, but I also went over it myself in Chinese with various translation aids. It raises more questions for me than answers, but according to the account, which I cite in the book, upon Anna May’s arrival in Hong Kong, she insulted a number of high-profile people from the Hong Kong film industry by refusing to shake their hands. Whether this was intentional is hard to say. Perhaps Anna May didn’t know who they were, never having seen or met them before? She was also excited to greet her sister Lulu, whom she hadn’t seen in years, so it’s possible she inadvertently ignored them. In either case, the response to this supposed snub was outsized and the crowd completely turned against Anna May, chanting things like “Down with Wong Liu Tsong!”

To escape some of the bad press, she quickly changed plans and went on a trip to the Philippines. She returned to Hong Kong with much less fanfare. Since things had quieted down, she was able to finally make the trip out to Toisan, where she visited her father and youngest brother, Richard. Footage of this happy reunion is in the documentary Anna May compiled of her travels. It’s a beautiful film housed at the UCLA Film & Television Archive. I wish more people could see it.

Blumberg-Kason: I do, too, and we are so fortunate to have your book and your vivid descriptions of this reunion! I can imagine how moving it was to research and write since you and Anna May have a lot in common. You were both born and raised in the Los Angeles area and your families—several generations removed—both came to the US from Toisan in southern China, the hometown of the earliest Chinese Americans two centuries ago. Can you talk about other famous Toisan descendants you came across in your research?

Salisbury: One of the reasons I was drawn to Anna May was because of her family background, which mirrors my own in many ways. My great-grandfather came to the US from Toisan around 1915 and started out as a domestic servant working for a wealthy American family in Los Angeles. Eventually, he saved up enough money to get married and open up a general store in Chinatown called Sam Ward Co., which many people still remember. I’m technically the fifth generation of my Chinese American family, so I relate a lot to Anna May’s constant dilemma of being seen as neither Chinese enough nor American enough.

One of the reasons I was drawn to Anna May was because of her family background, which mirrors my own in many ways.

One of the other well-known Hollywood personalities from Toisan was James Wong Howe, who broke into films around the same time as Anna May. He was a pioneer of cinematography and won two Oscars over the course of his career. Jimmy, as his friends called him, and Anna May worked together on two films and were lifelong friends.

Moon Kwan is another name who comes to mind. I’m not sure whether he was from Toisan, but he definitely hailed from the Guangdong region. He often worked in Hollywood as a technical consultant; for example, he advised D. W. Griffith on his film Broken Blossoms. He also had aspirations to write and direct. Eventually, he returned to China and cofounded Grandview Film Company, which produced Chinese-language films for diasporic Chinese in America. Moon was also friends with Jimmy and Anna May. They once hosted a joint Chinese New Year party in 1927 that was written up in the Los Angeles Times.

Blumberg-Kason: That sounds divine! You should re-create that party in 2027. Three years should be enough time to plan it! In the meantime, it would seem only fitting if your book were made into a movie or streaming series. Who would you cast as Anna May? You’d have to do a Hitchcock and cast yourself in a cameo at the very least. Which character or role would that be?

Salisbury: I’d absolutely love to see it made into a streaming series; that way you could go deeper into periods of Anna May’s life that I had to speed through in the book. I’ve always thought Lana Condor has a similar likeness to Anna May, especially for depicting her early years in Hollywood, but I’d be equally interested in seeing an unknown actress cast to play her.

As for a cameo—which is such a fun idea—I think I’d cast myself as one of the journalist friends in Anna May’s life. Maybe someone like Myrtle Gebhart, who wrote a delicious piece about her first meeting with Anna May. The interview was conducted as they drove around Los Angeles somewhat recklessly. Two flappers in a car living dangerously! The other person who comes to mind is Grace Wilcox. She and Anna May were quite close and remained friends for several decades. Grace hoped to one day write Anna May’s memoirs with her. Part of me will always wonder whether there’s a manuscript catching dust, sitting in someone’s garage!

Blumberg-Kason: That would all be fabulous, and wouldn’t it be a biographer’s dream to find unpublished manuscripts collecting dust in someone’s garage! Thank you so much, Katie, for our discussion about Anna May and your magnificent new book.