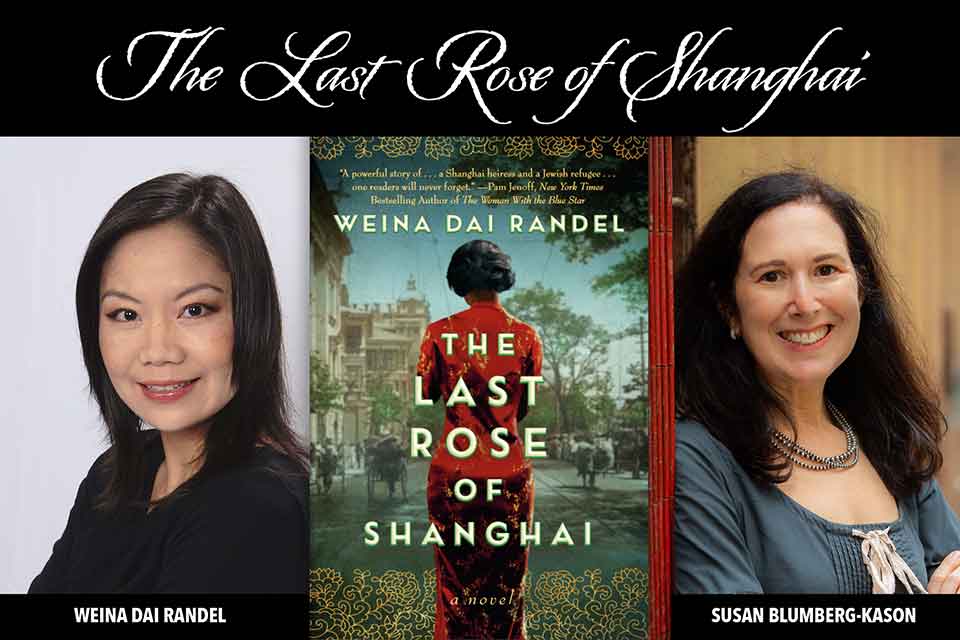

A Novel of Old Shanghai: In Conversation with Weina Dai Randel

Weina Dai Randel burst onto the literary scene a number of years ago with her duology about Empress Wu Zetian, China’s first woman leader. After winning the prestigious Rita Award in 2017 and seeing her novels translated into seven languages, she is back now with a new historical novel set in 1940s Shanghai. Keeping with her love of strong women characters, her new book, The Last Rose of Shanghai, centers on a nightclub owner named Aiyi Shao who falls for a Jewish refugee who had recently escaped Nazi Germany. Through their love of jazz, they develop a forbidden bond set during one of Shanghai’s most volatile and exciting eras. Randel is the first Chinese American author to write about Shanghai Jewish refugees, although there have been dozens of memoirs, narratives, and novels about this phenomenon from Jewish authors. We recently spoke over Zoom about what made Shanghai so special and why it matters now, along with the reasons Jews escaped to Shanghai during World War II and how Chinese and Jewish traditions are so similar.

Susan Blumberg-Kason: It seems that the popularity of 1930s and ’40s Shanghai rose both in China and the US about twenty-five years ago. Can you talk about the appeal of this time and why it’s so special, both to people in the US and China?

Weina Dai Randel: I think many aspects of Old Shanghai appeal to us today. From the late 1920s to the early 1940s, the period of Old Shanghai was a symbol of modernity and defines what Shanghai is today. There was a great deal of Western influence in Shanghai, especially in music, which is featured prominently in The Last Rose of Shanghai. Did you know China’s pop music originated in Shanghai?

Blumberg-Kason: I didn’t, but that makes sense because many popular songs in Hong Kong decades ago were sung in Mandarin, not the Cantonese that people speak there.

Randel: I didn’t know that at first and always thought Hong Kong music came first. Shanghai’s pop music began with a love affair with American jazz. Many American jazz musicians couldn’t find work during the Great Depression in Chicago and New York, so they traveled to Shanghai. Buck Clayton was a trumpet player who arrived in 1934 and worked with a very popular Chinese musician named Li Jinhui, who was considered the father of Chinese popular music. Li created a new type of music called shi dai qu, music of the times, which is enjoying a revival today. The movie In the Mood for Love played these songs. And if you watch the movie Crazy Rich Asians, you can hear them, too. The title of my book, The Last Rose of Shanghai, was inspired by one of Li Jinhui’s famous songs. I couldn’t use his lyrics because it’s very expensive to purchase rights, so I made up lyrics for the book.

Randel: I didn’t know that at first and always thought Hong Kong music came first. Shanghai’s pop music began with a love affair with American jazz. Many American jazz musicians couldn’t find work during the Great Depression in Chicago and New York, so they traveled to Shanghai. Buck Clayton was a trumpet player who arrived in 1934 and worked with a very popular Chinese musician named Li Jinhui, who was considered the father of Chinese popular music. Li created a new type of music called shi dai qu, music of the times, which is enjoying a revival today. The movie In the Mood for Love played these songs. And if you watch the movie Crazy Rich Asians, you can hear them, too. The title of my book, The Last Rose of Shanghai, was inspired by one of Li Jinhui’s famous songs. I couldn’t use his lyrics because it’s very expensive to purchase rights, so I made up lyrics for the book.

A renaissance in literature also took place during that period, as many poets and writers hosted private salons patronized by Chinese luminaries such as Lu Xun, Zau Sinmay, Xu Zhimo, Lin Yutang, and many more. They were joined by graduates of Western universities and debated traditional ways and Western thought. These writers produced many evocative stories and pithy essays that guided the resistance force then. Those essays are still read and studied by students at school today. Even when I was at school in China, I studied these essays.

Old Shanghai also saw a booming industry in fashion. Women wore fitted dresses called qipao that were stylized with superb craftsmanship and exquisite fabric that complements feminine figures. The qipao remains an emblem of the traditional Chinese dress style of Old Shanghai. Another fact about Old Shanghai was that women were actually allowed to work. In the 1930s women in the US were generally not allowed to work, but in Shanghai women found jobs as calendar girls, taxi dancers in the nightclubs, and posed for ads for cigars and whisky.

For people in the US and Europe, I think they have fond memories of Shanghai as an entertainment city. Here, neon lights of the nightclubs flickered all night long. The nightclub in The Last Rose of Shanghai, called the Paramount in English, was one of them. Luxury hotels and apartments spread lush Persian rugs on tessellated floors, and nimble Russian dancers clad in sexy dancewear performed ballet and the cancan. Wealthy businessmen smoked cigars and bet on horses at the racecourse. And the latest movies, like Shanghai Express and Gone with the Wind, attracted many moviegoers in the cinemas. Americans, Russians, and Europeans lived like kings, and they were adored like masters and welcomed for their business activity. Shanghai was home to writers, poets, architects, bankers, opium traders and spies, and international criminals.

Many poets and writers hosted private salons patronized by Chinese luminaries such as Lu Xun, Zau Sinmay, Xu Zhimo, Lin Yutang, and many more.

Blumberg-Kason: I love how you cover so much of that in your in your book because it gives us a great picture of the time. At the end of your story, you include a reading list for people who’d like to know more about this period. What stands out about this list is that there are no Chinese or Chinese Americans who write about Shanghai Jewish refugees. You’re the only Chinese American writer to do so. Why do you think it’s taken so long, and are there books written in Chinese about this topic?

Randel: There are many academic papers by Chinese Americans and Chinese Canadians that investigate the lives of Shanghai Jewish refugees, although few are book-length works. Many Chinese writers of course have written about their struggles under the Japanese occupation, like the Nobel Prize winner Mo Yan. But in China, after World War II, there was a civil war and after that was the decade-long Cultural Revolution. Many writers and poets were sent to reeducation for ten years, and they wrote about their experiences during that time after they came back—these works were called scar fiction. Somehow the story of Jewish refugees during World War II was overlooked.

Blumberg-Kason: It’s interesting because over the last couple of decades I've seen more books about these stories, which seems to correspond to the rising demand for books about 1930s and ’40s Shanghai. What is it about the Jewish refugees that makes for such a fascinating story? Shanghai was one of the only places in the world to take Jews without papers then, perhaps up to 24,000 from 1933 until 1941. But certainly, other countries cumulatively took in more.

Shanghai was one of the few places in the world to take Jews without papers then, perhaps up to 24,000 from 1933 until 1941.

Randel: First of all, I would say China was a strange and alien land to many Europeans in the 1940s. Chinese had different customs, different facial features, and spoke different languages. To many Europeans Shanghai was a land of the unknown. It was the last straw for the Jews to go to Shanghai.

But look at how they were received! This is the most unique part of the experience, I think. The Jews were persecuted and dehumanized in Europe but were never confronted by similar threats in Shanghai. It’s safe to say there was no anti-Semitism among the Chinese. (But there was among the British and German residents in Shanghai.) And that has much to do with Chinese culture. Confucianism was the philosophy embraced by many educated people in China, which promotes tolerance. And many less-educated men and women believed in Taoism and Buddhism, which value peace and acceptance. Throughout China’s history, dynasty after dynasty, there has been a culture of absorbing and integrating the alien and the foreign into the cultural fabric. Many Chinese people also had a hard time differentiating Judaism, Christianity, and Catholicism. To them, all foreigners were considered invaders because of the Opium Wars.

I was not alive during that time, but I can tell you a tale I heard while at college near the former Jewish ghetto in Shanghai. After Pearl Harbor, Jewish refugees were confined to this ghetto under the strict surveillance of the Japanese. They were unable to leave the area, unable to receive any food, and starved for days. So to support them, Shanghai locals threw loaves of bread into the alley because they couldn’t enter the ghetto. From my novel, you will know that the local Shanghainese were also destitute under the Japanese occupation, but they still went out of their way to help the refugees. Now, we probably can’t verify this story, but none of the Jewish refugees who wrote memoirs refuted this tale. Instead, they wrote of fond memories of coexisting in harmony with the locals and the friendships they fostered. They talked about how they were invited to homes to eat dumplings with soy sauce; they reminisced about the small Jewish community called Little Vienna with their own German newspapers, regular new theater gigs and cafés.

So I think it’s apt to say the survival of Shanghai Jews is also a story of how we as different races and as human beings shine and triumph over war and adversity.

Blumberg-Kason: You have your own Chinese-Jewish family background. When you met and married your husband, what kind of cultural differences did you experience that were decidedly Jewish and not just American? And what were your greatest surprises when it comes to the similarities?

Randel: We broke a glass at our wedding, which is a Jewish custom, but I didn’t know what that meant then. Our love story was kind of unconventional and American at the same time. We met at work in Shanghai and then flew to Las Vegas for a simple wedding attended by about ten people. My parents were not there, nor were any on my side of the family. As for Chinese and Jewish cultures, we both hold great reverence for education. I also think both Chinese and Jewish people have a very strong sense of family bonds.

Blumberg-Kason: Yes! Many of our holidays are centered around food. There’s the Mid-Autumn Festival and Rosh Hashana, Passover and the Lunar New Year.

Randel: We also have special occasions to remember our ancestors. Chinese have the Qing Ming Festival, where families sweep their ancestors’ graves and burn incense. And you light candles and preserve your memories of your beloveds at their yahrzeits.

Blumberg-Kason: I hadn’t thought about the yahrzeits and Qing Ming as being similar, but you’re so right! Getting back to your novel, I love that you include so many important historical figures. You are a master of historical fiction, and including real people makes your story much more exciting. How did you learn about figures like Victor Sassoon, Zau Sinmay and his wife Sheng Peiyu, Emily Hahn, Eileen Chang, and Laura Margolis?

Randel: I started with Zau Sinmay, and I realized he had six siblings. He also had an aunt, Sheng Aiyi, who was considered to be the first female entrepreneur in China. She was the owner of the Paramount nightclub. Because of that, I made Aiyi the main character in the book. I actually don’t know the name of Sinmay’s youngest sister, so the historical figure I based her on was Sheng Aiyi, Sinmay’s aunt, who was also connected to Peiyu’s family. Sheng Aiyi was also a friend of Madame Chiang Kai-shek and almost became her sister-in-law. Almost.

If you look at the landscape of Shanghai, Victor Sassoon’s shadow was everywhere. The Peace Hotel was a hotel for many prominent politicians and wealthy people. I went to the Peace Hotel a few years ago and saw “Sassoon House” engraved in stone above one of the entrances. I was shocked. Sassoon owned eighteen thousand properties in Shanghai. It was hard to characterize him because his family were opium dealers, and he received his wealth that way, and you know how people in China viewed opium. But he made significant contributions to the Jewish refugees when they arrived in Shanghai. He gave them the entire floor of the Embankment House, which he owned. He also gave them milk money so they could start businesses, about fifty thousand US dollars all together. That was a lot of money back then.

Laura Margolis ran the Joint Distribution Committee, or JDC, in Shanghai to help Jewish refugees. When she was arrested by the Japanese and was about to be sent to a POW camp in the Pudong district of Shanghai, she hid her correspondence in her underwear. I thought that was so courageous, and she had to appear in the story.

Blumberg-Kason: Finally, can we talk film? There have been more than a handful of movies about 1930s and ’40s Shanghai, both in East Asia and the US. The ones in the US seem to have bombed, like The White Countess, Shanghai, and Shanghai Kiss, but Chinese-language movies like Red Rose, White Rose, based on an Eileen Chang story, and some Zhang Yimou films like To Live and Shanghai Triad have generally done well. If you had to cast your novel for a film adaptation, who would you pick to play the main characters?

Randel: We just finished casting the audiobook characters, and it was nerve-racking but very exciting. I would love for the book to become a movie and for Kevin Kwan to produce it. I think he did a very good job with Crazy Rich Asians and put a touch of Old Shanghai in it. Ang Lee is the first person who comes to mind since he directed Eileen Chang’s short story “Lust, Caution.” But my husband won’t watch it because he says it’s porn.

Blumberg-Kason: It kind of is, but it’s probably the movie Americans know best from Eileen Chang!

Randel: I still haven’t watched it, but I think Ang Lee would be perfect to direct a film based on my book. Or Chloe Zhao. And of course Zhang Yimou can make anything about Shanghai shine. For the leading men and women, I’m a little out of touch with movie stars. I don’t usually watch TV. Any Jewish American actor and Asian American actress will do, I think.