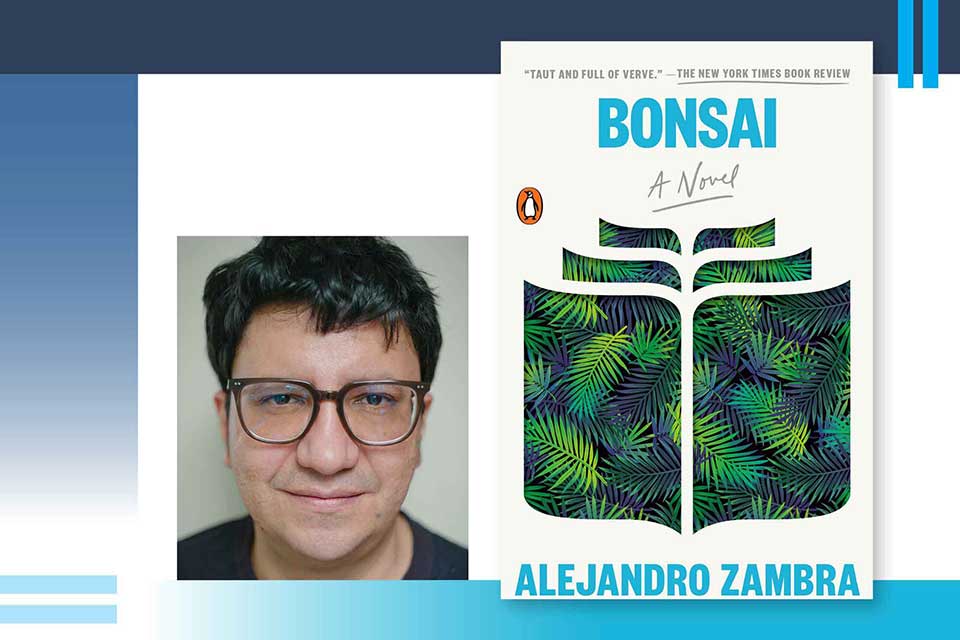

Wanting to Write a “Bonsai of a Novel”: A Conversation with Alejandro Zambra

Over the past decade or so, the Chilean writer Alejandro Zambra (b. 1975) has emerged as one of the most inventive and influential writers of his generation. Named to Granta’s Best of Young Spanish-Language Novelists issue in 2010, his books have ranged from the miniaturist Bonsai and The Private Lives of Trees to the nostalgia-tinged Multiple Choice and Ways of Going Home. His work has embodied what he’s called Chile’s “literature of the children”: fiction written from the perspective of those who grew up during the dictatorship of the 1970s and ’80s.

This past winter, Viking published Zambra’s latest novel, Chilean Poet—which further probes the complicated relationship between art and life (and step-fatherhood)—and this summer Penguin will release a new translation of his first novel, Bonsai, by longtime collaborator Megan McDowell. We spoke via email about his beginnings as a novelist, literary “maturity,” and the effects of leaving Chile.

Anderson Tepper: When Bonsai was originally published in 2006, you were primarily known as a poet and critic. What prompted you to write a novella—or, as you put it, a “bonsai-book”?

Alejandro Zambra: Well, it is a short book with a long story. . . . One morning in 1998 I came across the photograph of a tree wrapped in a sheer fabric. It was in the newspaper. The image belonged to the series Wrapped Trees, by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. I think at first I didn’t like the image. But I kept thinking about it, so I understood there was something there. That image challenged my idea of beauty. I wrote a bad poem that talked about wrapped, restricted trees. Later I became unreasonably interested in bonsais, so I started trying to write a book about them. I read a lot about them and came to the idea that writing was like taking care of a bonsai: to prune the branches until you make visible a form that was already there, lying in wait; writing as illuminating language so the words say, for once, what we want to say; writing as trying to read an unwritten text.

I wanted to write a book called Bonsai; or maybe what I really wanted was to read it, although I didn’t really like bonsais. Their controversial beauty led me to a story that I didn’t want to tell but rather only to evoke: The story of a man who, instead of writing—or living—chose to stay home watching a tree grow. That man wasn’t me, of course, but rather a blurry character that I gazed at from a certain distance. Anyway, I don’t remember the precise moment when Bonsai started to be (or seem like) a novel. I distrusted fiction; I especially distrusted my ability to tell a story, or that I even had a story to tell. I didn’t want to write a novel, but rather the summary of a novel. A bonsai of a novel.

I didn’t want to write a novel, but rather the summary of a novel. A bonsai of a novel.

Tepper: The book created a stir in Chile and was heralded as the beginning of a new era in the country’s literature. How did it open up a different path for you as a writer?

Zambra: Well, when it was published I wasn’t sure I was becoming a “novelist” or something like that. . . . But I think that novel contained the seed of The Private Lives of Trees. They are linked, literally. And in a way, The Private Lives of Trees is a book “against” Bonsai. And so on. There is a passage in The Private Lives of Trees that contains the seed of Ways of Going Home. I mean, I like the idea that you always write the same book, but the new one happens to be very different from the previous one because you have changed and the world has changed. So maybe Chilean Poet was like my way of rewriting Bonsai fifteen years later.

Tepper: Bonsai came out in 2008 in the US as part of Melville House’s Art of the Novella series, translated by Carolina De Robertis. Why did you decide to have it retranslated now, and did Megan McDowell approach the text any differently?

It is an unusual luxury to have two different versions of the same book.

Zambra: Oh, it wasn’t my decision, although I’m very happy about it. The idea started because Bonsai was never published in the UK, and Megan was going to do a translation for Fitzcarraldo. In the meantime, Penguin started publishing my backlist, and they also decided to publish Megan’s new translation. I’m really thankful. It is an unusual luxury to have two different versions of the same book.

The whole story of this book in English is beautiful. In 2006 or 2007, Daniel Alarcón (a writer I didn’t know back then), came across the book and liked it. He was in the process of editing an issue of the Virginia Quarterly Review, and he asked Carolina de Robertis to translate Bonsai so he could include it. As the novel was so short, they published it in its entirety, and that was the version that Dennis Johnson from Melville House read. A few weeks before the book was published, Megan McDowell wrote to me because she wanted to translate Bonsai. I thanked her but said it was taken. She was very sad because she had already started translating it, out of enthusiasm, for a translation workshop she was taking. . . . In the end, she translated The Private Lives.

So this “new” translation was started many years ago, although Megan said to me that she made many changes to her own version after all this time. I am not in the position of comparing both translations. I love them both, and I think they belong to their authors/translators. In this case, I think my book is the score they both sing, each one in her own style.

Tepper: Did you work closely with Megan, and what was it like for you to revisit this early version of yourself as a writer?

I always work closely with her, because she has become one of my greatest friends on this planet. But if I were dead, I think the book would be the same. I haven’t read this book in a long time, but I had to read it this year due to reprintings both in Spanish and English. I wouldn’t know how to put my feelings and thoughts on paper. I mean, I don’t feel like I could express strong and serious and distanced literary opinions. Rereading a book of your own is more like looking at old photographs, or having lunch with your kid once he’s become a very independent young person.

Rereading a book of your own is more like looking at old photographs, or having lunch with your kid once he’s become a very independent young person.

Tepper: How does Chilean Poet represent a more mature engagement with some of the themes that you’ve teased out over the course of your work?

Zambra: I don’t know. Maybe now I am less mature than then. . . . In a way, I hope so. I don’t like to compare my books, I don’t want them to be fighting. They are not competing, they are more like half-brothers. . . . They have different dads but the same mother, me.

Tepper: You began writing Chilean Poet while in New York on a fellowship and finished in Mexico City, where you live now. Did leaving Chile have an effect on the writing of this book in any way?

Zambra: Yes, of course. In many ways. The novel ends in early 2014, when I started to move from Chile. I met Jazmina [his wife, author Jazmina Barrera] in New York, and when we were both leaving the city we had to decide whether to live in Santiago or Mexico City. So we flipped a coin and . . . no, of course it wasn’t like that. We decided that I was more “portable” than her for our parenting plans, so I moved to Mexico City. But early on I started experiencing a bad nostalgia, a deep homesickness, so I asked myself what kind of Chilean-who-lives-abroad I was going to become. Writing that novel was my way of dealing with that paralyzing and bitter feeling. I needed four hundred pages of warm and lighthearted nostalgia. . . . Also, this is related to the conversational rhythm of it. It is more like a “spoken” novel, I like to think. And also it is my most novel-ish novel, definitely the one that most resembles the traditional idea of a novel, very different from the things I started working on after I wrote it.

As I work through this question, I realize I could write a more-than-400-page answer; so I am going to end here because I believe we all have much more urgent things to do.

June 2022

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!