Happy Birthday, Roberto!

illustration by Michael Hoeweler.

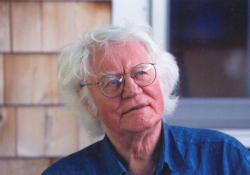

This started out as a book review of Roberto Fernández Retamar’s Poesía nueva reunida (Letras Cubanas and Ediciones Unión, 2009) but may turn out to be a tribute to the Cuban poet, and friend, who celebrated his eighty-fifth year on June 30, 2015. The volume of more than four hundred pages includes the poems he has wanted to preserve from all but a couple of his earliest books as well as those written since the most recent appeared. The first are from 1948, the last from 2007.

For any prolific eighty-five-year-old poet, the arc of work is important. It speaks of growth, changes in concerns and perception, and also those constants that persist. For a Cuban poet of Roberto’s age, however, this arc has its before and after: before and after the 1959 revolution that set his country in a dramatically different direction and required its citizens to take sides.

Among those who would become poets, few played a military role in the war or held a political position in the rear guard; but most who remained in Cuba welcomed the overthrow of the dictator and the promise of a more just society.

Retamar has referred to himself and his contemporaries as “men of transition.”[1] Among those who would become poets, few played a military role in the war or held a political position in the rear guard; but most who remained in Cuba welcomed the overthrow of the dictator and the promise of a more just society. Of these, a good many threw themselves into the complex work of social change.

From the beginning, Roberto occupied a privileged place in the new cultural panorama. He went to work at Casa de las Américas, the important arts institution founded and directed by revolutionary heroine Haydée Santamaría. Under her guidance, and contributing his own vision as well, he founded Casa’s singular journal, Revista Casa (which recently celebrated its first fifty years!), and inaugurated the prestigious literary contest that continues to draw submissions in a range of genres from all over the Spanish-speaking world. Since 1990, he has been the institution’s president and, as such, a member of Cuba’s Council of State.

Retamar debated the most pressing issues unfolding over these years of revolution, engaging with dozens of artists and intellectuals: some of the most influential of his and successive generations, such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Roberto Matta, Gabriel García Márquez, Julio Cortázar, Eduardo Galeano, Pablo Neruda, Roque Dalton, José Lezama Lima, Ambrosio Fornet, Fina García Marruz, Mario Benedetti, Marcia Leseica, Thiago de Mello, Mario Vargas Llosa, and Juan Gelman. In this compendium there are moving poems to some of them.

He has written pivotal essays as well as poetry and other texts. In 1967, with Ensayo del otro mundo, he redefined modernism by emphasizing its ideological content. In 1971, his Calibán refuted the work of the Uruguayan writer José Emilio Rodó and got readers to look at culture and identity from the viewpoint of the Global South. These texts continue to be influential in accessing the ideas of several generations, and useful in looking to the future.

All this would be enough to situate Retamar as a major intellectual in a particularly interesting country who has had the good fortune to live through its most demanding and exciting years. But his poetry is where his experience, mind, and heart come together, producing those lasting moments that represent the best of what he is. In this book’s introductory note, he writes: “From a rigorous point of view, I’m one of those who believes that a poet, in very auspicious moments, is able to write . . . a few poems that will outlive him.”[2] The poems reproduced from early volumes are often modernist in construction, socially conscious in that vague way of texts written before life itself demonstrates something else is possible, pastoral in the sense of an island dweller in love with his strip of land, erudite in their references to the classics, and in conversation with such predecessors as Antonio Machado, Juan de Unamuno, Gabriela Mistral, William Blake, Alfonso Reyes, Rubén Darío, José Martí, and Ezequiel Martínez Estrada.

With Sí a la revolución [1958–1962], the poems change dramatically. This is not only because there is new, uncharted, subject matter. The voice is also new. It rises to the challenge of engaging events and feelings too often rendered in clichéd language into a language that does them justice. The poet weds a conversational style to a rigorously practiced formalism. Here Roberto makes poems from the threat of invasion, from watching his daughters participate in a new kind of life, and from other experiences that would not previously have seemed the stuff of verse. “La isla recuperada” and “El otro,” both from 1959, are among my favorites from this period. The latter was written on the very day of the January 1stvictory. In it the poet asks:

We, the survivors,

To whom do we owe our survival?

Who died for me in the condemned man’s cell,

Who received my bullet,

The one meant for me, in his heart?

Who died so I could live,

His bones inhabiting mine,

The eyes they gouged from him,

Looking out from my face,

And the hand no longer his

And not yet mine

Writing broken words

Where he is no more, living on?[3]

That book and Que veremos arder [1966–1969], together, form the bridge: between the old and the new. In Retamar, the old lives in the new and the new nourishes itself with the old. As with many of our generation (and I include myself, although I am a few years younger), Vietnam loomed large in our consciousness. In 1970 Roberto was in the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, traveling from Hanoi south to the 17th Parallel. That experience produced such extraordinary poems as “Imágenes” and “Esta noche de domingo en La Habana que es esta mañana de lunes en Vinh.”

It may be that Juana y otros poemas personales [1975–1979], with such iconic works as “¿Y Fernández?”, “Carlos Fonseca habla de Rubén Darío,” and “Hace / dentro de / veinte años,” represents the poet’s voice at its richest. Certainly the voice, now unmistakably his, has become exceptionally fine-tuned.

Fernández Retamar breaks through stylistic limits to join passion and memory in profoundly evocative ways.

Among the poems from later books, “Última carta a Julio Cortázar” and “Con Haroldo Conti para que como Haydee nunca se muera” are personal favorites. Undoubtedly this is because Julio Cortázar and Haydée Santamaría were important figures in my own life, but it is also because Roberto’s approach to both outstanding human beings breaks through stylistic limits to join passion and memory in profoundly evocative ways.

In his introductory note, Roberto writes: “. . . in times like ours, that leave open wounds in our flesh, it’s not a bad thing to put one’s cards on the table.”[4] This, perhaps, has been his greatest poetic accomplishment: to have written about the ordinary-extraordinary in ways that bring it to life. Entering his eighty-sixth year, he still writes powerfully. I have every reason to believe there are more great poems ahead. Poesía nuevamente reunida is both a tribute to a life in poetry and a promise of things to come.

Albuquerque

[1] “Usted tenía razón, Tallet, somos hombres de transición,” in Buena suerte viviendo [1962–1965].

[2] RFR, Poesía nuevamente reunida, 8. Translation my own.

[3] “Nosotros, los sobrevivientes, / ¿A quiénes debemos la sobrevida? / ¿Quién se murió por mí en la ergástula, / Quién recibió la bala mía, / La para mí, en su corazón? / ¿Sobre qué muerto estoy yo vivo, / Sus huesos quedando en los míos, / Los ojos que le arrancaron, viendo / Por la mirada de mi cara, / Y la mano que no es su mano, / Que no es ya tampoco la mía, / Escribiendo palabras rotas / Donde él no está, en la sobrevida?” Translation my own.

[4] RFR, Poesía nuevamente reunida, 7: “. . . en tiempos como los nuestros, tan en carne viva, no viene mal que las cartas estén bien a la vista.” Translation my own.

Editorial note: Dr. Fernández Retamar was interviewed in and provided a list of recommended books on Cuba to the March 2015 issue of WLT, and a number of poems as well as essays by and about him—including Nancy Morejón’s “For Roberto, on Turning Seventy?”—were featured in our Summer/Autumn 2002 issue.