Blurring the Real and the Fantastic: Victor Pelevin’s The Blue Lantern and Other Stories

Victor Pelevin is one of the most interesting writers to have come out of contemporary Russia. Though not widely known in the West, Pelevin is a cultural phenomenon in his native land; his work is read, anthologized, and analyzed by everyone from high school students to literary critics. He has been cast, alternatively, as a surrealist, postmodernist, absurdist, Zen-Buddhist, counter-culturist, new-sincerity-ist—and not without reason. His characters range from a Russian civil war hero (Chapayev and Void) to a vixen hypnotizing men with her fox tail (The Sacred Book of Werewolf), a woman transformed into a prying mantis (The Hall of Singing Caryatids), and, most recently, a drone cameraman from a dystopian Big Byz (S.N.U.F.F.).

Victor Pelevin is one of the most interesting writers to have come out of contemporary Russia. Though not widely known in the West, Pelevin is a cultural phenomenon in his native land; his work is read, anthologized, and analyzed by everyone from high school students to literary critics. He has been cast, alternatively, as a surrealist, postmodernist, absurdist, Zen-Buddhist, counter-culturist, new-sincerity-ist—and not without reason. His characters range from a Russian civil war hero (Chapayev and Void) to a vixen hypnotizing men with her fox tail (The Sacred Book of Werewolf), a woman transformed into a prying mantis (The Hall of Singing Caryatids), and, most recently, a drone cameraman from a dystopian Big Byz (S.N.U.F.F.).

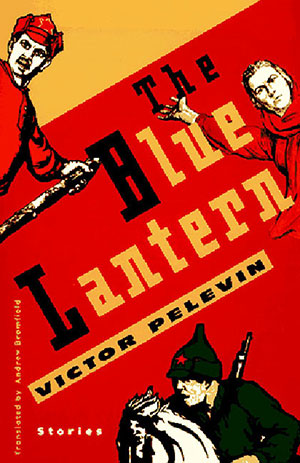

Pelevin is an undisputed master of the surreal who revels in pushing ideas to the absurd. Yet by the unaffected way with which he renders complex thoughts and emotions, Pelevin’s prose can be strangely reminiscent of Russia’s greatest realist, Leo Tolstoy. Like those of Tolstoy, Pelevin’s most memorable characters are ordinary people struggling with the ruthless waves of history. His magic mirror, replete with fantastic ploys and guises, works ad absurdum, meaning that it distorts reality only to reveal life as it is. The Blue Lantern, a collection from 1991 (translated by Andrew Bromfield and published by New Directions in 1997), holds a special place in the writer’s impressive oeuvre: unaffected by the many “isms” that came to characterize his later work, these stories offer a rare opportunity to study strangeness that mesmerizes while never ceasing to feel real. They also grant insights into a post-totalitarian society and illuminate a few enduring properties of that elusive concept known as “the Russian soul.”

* * *

A Russian girl travels to a site of a World War II plane crash to raise a German pilot from the dead and marry him. A cadet officer high on cocaine dreams of an ancient demon flying towards a city “crowned with thousands of golden church cupolas” while patrolling the streets of St. Petersburg on the eve of the Bolshevik Revolution. Such are the glimpses of the universe created by Victor Pelevin. “The world is a strange place,” confides one of the characters in his story collection The Blue Lantern, incidentally summing up Pelevin’s writing credo. Building on the “fantastic” tradition of his two great predecessors, Mikhail Bulgakov and Nikolai Gogol, Pelevin makes us believe in the strangeness of everyday things.

Building on the “fantastic” tradition of his two great predecessors, Mikhail Bulgakov and Nikolai Gogol, Pelevin makes us believe in the strangeness of everyday things.

The Russian mind, perhaps like no other, is conditioned to operate in the blurry zone between the normal and the abnormal: when you don’t accept the immediate world as normal, you poke around in all sorts of adjacent places. A visual metaphor for many of Pelevin’s stories would be Tarkovsky’s 1979 movie Stalker, in which a Poet, a Scientist, and a Guide (Stalker) go into the “Zone” to have their innermost desires fulfilled and, while they are at it, find the meaning of life. That an average Russian forest is almost indistinguishable from the apocalyptic “zones” of Pelevin and Tarkovsky—with its abandoned military bases, old mines waiting to detonate, trenches filled with rainwater and disintegrating partisan shelters—helps the leap onto the other side; in fact, it is never a leap but a step. Or a change of angle.

The Russian mind, perhaps like no other, is conditioned to operate in the blurry zone between the normal and the abnormal: when you don’t accept the immediate world as normal, you poke around in all sorts of adjacent places. A visual metaphor for many of Pelevin’s stories would be Tarkovsky’s 1979 movie Stalker, in which a Poet, a Scientist, and a Guide (Stalker) go into the “Zone” to have their innermost desires fulfilled and, while they are at it, find the meaning of life. That an average Russian forest is almost indistinguishable from the apocalyptic “zones” of Pelevin and Tarkovsky—with its abandoned military bases, old mines waiting to detonate, trenches filled with rainwater and disintegrating partisan shelters—helps the leap onto the other side; in fact, it is never a leap but a step. Or a change of angle.

But where to start? There are many well-traveled avenues into strangeness. Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina suffers from persistent nightmares that foretell her death; Bulgakov’s Pontius Pilate experiences a series of ominous visions triggered by the heat and a raging migraine during the questioning of Jeshua (Jesus). Among other “entry” options are drugs, injury-related comas, clinical death, shamanism, onset of madness, or a combination of the above. A writer can use virtually any trigger to signal his intention to enter the borderline state, and for the most part, the reader will go along because our minds are attracted to strangeness. Some writers, like Cortázar, build up the strangeness by subtle shifts of viewpoints and by manipulating the amount of text allotted to “strange” versus “normal” (as in his Blow Up collection). Some, like Bulgakov, by confident authorial comments on the initial irregularities of the story setup hitherto unknown to the reader (the opening of Master and Margarita).

Pelevin starts with the strange—and gives no explanation. In “The Tambourine of the Upper World,” the very first character the reader sees is a woman traveling on a local Moscow train, on whose shirt one can spot, among other things, “zigzag iron arrows, two Medal of Honors, tin face . . . and on her right shoulder, hanging from a Cross of St. George ribbon, there were two long rusty nails . . . and the round dial of an alarm clock sewn to her left legging and a horseshoe fastened to her right legging with a lavatory chain.” The train is familiar and, therefore, real; the woman, with her Mongolian face that resembles “a three-day-old cafeteria pancake curling up at the edges,” is also recognizable in a country that has spent centuries under the Mongol yoke. We accept the reality of the woman and of the train—as we accept her unusual dress. We’re prepared for things to get stranger still.

In the second story, “Crystal Ball,” the onset of strangeness is equally immediate: “Anyone who happened to sniff cocaine on October 24, 1917, on the deserted and inhuman avenues of St. Petersburg, knows for certain that man is not the king of creation.” The opening line is arresting because cocaine sniffing is not what one typically associates with the Great October Revolution. But the wet darkness of St. Petersburg’s night, the Shpalernaya Street, the wind whistling down the drainpipes are as real as the forthcoming revolution itself. The subject matter of the cadet officers’ conversation furthers the story’s hold on our attention: they talk about each man’s unique mission in the world; not an unusual subject for a Russian per se, yet in the story it acts like a louder note in a crescendo. In a brief lapse of consciousness, one of the officers, Yury, dreams of “a formless swirling mass of emptiness radiating icy cold” that closes in on a city “crowned with golden church cupolas that seemed to hang inside a crystal ball.” Our hearts stand still. There’s hardly another night in Russian history as important and as tragic as that of October 24, 1917, after which old Russia will no longer exist. It doesn’t matter that we readers know the outcome. We want to know what might have been. Our engagement is achieved by the urgency of the premise as much as by the strangeness of the officers’ pursuits.

As the second story unfolds, Pelevin continues to mix ordinary with extraordinary: the demon from Yuri’s drug-induced dreams attempts to slip into the reality of Shpalernaya Street in different guises—an old woman, a middle-aged man, and a wounded veteran in a wheelchair. All three share Lenin’s now-famous kartavost, or inability to roll the “r,” and all three try to get past the cadet cordons to Smolny, soon to be the headquarters of the revolution. (Here we readers are smarter than the characters, but it’s a sad smartness based on historical perspective.) Pelevin’s three demons do not have goat hooves or tails, but their placement in the story makes them instantly recognizable. Three times the cadets repel evil, but then their vigilance fails: accompanied by a muffled rattle of bottles that is vaguely reminiscent of kartavost, “a typical class-conscious proletary” pushes a yellow cart inscribed “Lemonade” toward Smolny. The demon wins. The crystal ball, Russia, is lost. What stays is the “cold, wet and dirty Shpalernaya Street,” with its “houses that loomed like the walls of that deep dark fissure beyond which, if an ancient poet is to be believed, lies the entrance to Hell.” It’s up to the reader to decide what Shpalernaya Street really is. Pelevin furnishes convincing evidence for both.

Perhaps ironically, Pelevin’s phantasmagorias are nothing but shortcuts to some very simple truths: history always hangs by the thread; love, if it’s real, is always a matter of life and death.

If in “Crystal World” the snorts of cocaine act as a formal switch between the two realities, in “The Tambourine of the Upper World” the reader is drawn deeper and deeper into a sense of strangeness by the relentless logic of the story. The Mongol-faced woman on the train, with which the story starts, is not the main character; she is the conduit, a shaman hired by the story’s protagonist, Masha. Masha’s goal is simple: to resurrect a dead German pilot, marry him, obtain an immigration visa, and get out of Russia. The premise might sound fantastic at the execution level, but not at its core. Two devastating wars of the last century have left Russian women with a major problem: all good men are dead. So to get a good husband, through the story’s logic, one needs to look among the dead. Conveniently, Russian forests swarm with dead foreign invaders, whose passports and citizenships have never been repelled and who can help a girl’s upward mobility. This allows Tanya, Masha’s girlfriend, to start a business of resurrecting dead foreigners for a fee with the help of a shaman who, until Tanya moved her to Moscow, lived somewhere in the Far North. And so Masha became a client of Tanya. She researched and identified a location of a downed World War II German plane. In the apocalyptic world of post-Soviet Russia, where people wandered, dumbfounded, amidst the ruins of empire, where all sorts of “businesses” were springing up, stranger things have happened. When the shaman performs a calling-from-the-dead dance at the site of a crashed plane, everything makes sense in the bizarre logic of the early 1990s Russian reality and in the perfect logic of Pelevin’s story.

A mark of a great storyteller is the ability to build certain logic and then disrupt it. In the case of “The Tambourine,” the pilot who comes out of the wrecked plane is not German but Russian; he was shot down by mistake when moving a captured German plane. Major Zvyagintzev, with his “broad face with a calm expression, a slightly turned-up nose and several days’ stubble on his cheeks,” is useless to Masha because he has no foreign passport. This is where the story stops being “magically realistic” and becomes magical: Major Zvyagintzev, a handsome hero whose right to be in the “Upper World” has come with a bullet in his left temple, is the man whom Masha can love, must love, would have loved, had he not been shot dead.

The “Upper World” where Major Zvyagintzev lives is “very quiet, very nice” and has “something like a house and a plot of land,” a washer, a microwave; it is from this world that he was summoned by the shaman’s spell, and to which he must return. The Germans, who dwell in the “Lower World”—Pelevin’s metaphor for Hell—can make decent zombie-husbands; the major, who died protecting his motherland, belongs in heaven, not with Masha on earth. But before shooting himself through the left temple so that he could return to the plane, the major leaves Masha—whom he calls beautiful—a reed pipe: if she plays it, he would come to get her. To obtain love and happiness, like Bulgakov’s Margarita and many before her, Masha must die. She walks away, “clutching the reed pipe that Major Zvyagintzev had given her and thinking very hard.” The reader wants Masha to be happy and, therefore, to play that pipe.

Strangeness for strangeness’ sake does not interest Pelevin; when he cracks open the door into another reality, it is to glimpse eternity.

Perhaps ironically, Pelevin’s phantasmagorias are nothing but shortcuts to some very simple truths: history always hangs by the thread; love, if it’s real, is always a matter of life and death. His dreams and satires never become tall tales. No bloody vampires await around the corner to tickle the readers’ nerves and no flying carpets carry his characters away to safety. Strangeness for strangeness’ sake does not interest Pelevin; when he cracks open the door into another reality, it is to glimpse eternity. Pelevin’s gift to make reality out of fantasy is reinforced by his ear for modern idiom, some of which are rendered in the translation by non-dramatic dialogues, by precisely drawn physical details. The reader can never figure out when exactly she was asked to suspend her disbelief: the stranger things become, the more real they feel. Pelevin is fully in control of his universe, and his confidence is catching. The reader believes in the world according to Pelevin.

San Francisco