Nuruddin Farah’s Crucible of the Imagination

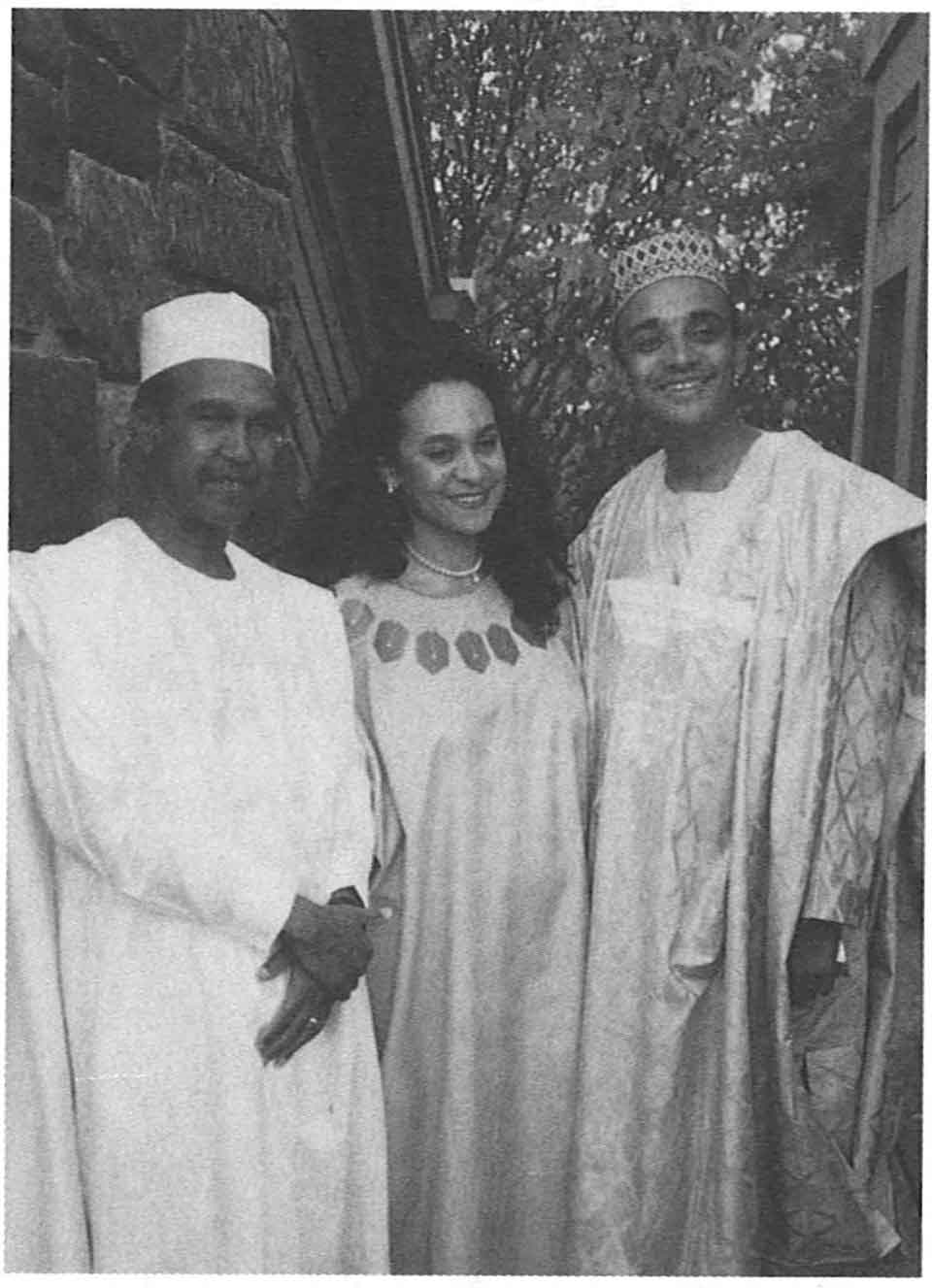

of Oklahoma in October 1998 / Photo by Gil Jain

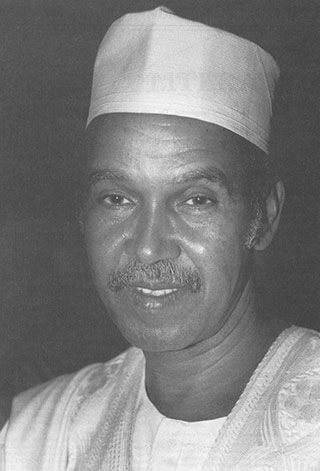

Today (November 24) marks the seventy-fifth birthday of Somali writer Nuruddin Farah, recipient of the 1998 Neustadt Prize. The following tribute by Kwame Anthony Appiah appears in Dispatches from the Republic of Letters: 50 Years of the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, published by Deep Vellum in October. The anthology, compiled by WLT’s editor in chief, Daniel Simon, gathers the acceptance speeches by the first twenty-five laureates of the prize along with tributes by the jurors who nominated them. Kenyan writer Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o nominated Farah for the prize.

I know exactly why I remember so very well the first time I met Nuruddin Farah: it is because he made me laugh. Not just a wry smile or two, or a modest guffaw. He made me laugh so much that my abdominal muscles ached for days; so much, that I had to beg him to stop talking for a while, because I was doubled up, about to fall to the ground. I remember, too, what it was that he was so funny about. He was telling stories about a meeting with another great African writer, the South African author Bessie Head, whose eccentricities he was delineating with a mixture of gentleness, puzzlement, and profound respect. He was not telling stories against her: I remember thinking that if Bessie Head was listening somewhere, from beyond the grave, she would have understood at once that Nuruddin’s stories and my laughter were a celebration of her; there was no mockery. What I don’t remember is where we were—it must have been a conference about African writing—or when it was.

Though I remember my laughter, I don’t remember the stories. But even if I did, I know I couldn’t tell them as he did, catching each ebbing wave of laughter with another tale slipped in to return me to convulsions. So Nuruddin was locked away in my mind and heart forever not just as the marvelous writer I had read and heard of before I met him, but as this wonderful teller of stories.

I think of this anecdote as emblematic: for this was, as I say, a story about a woman—a crazy woman, but also a great writer. And anyone who has read any of Nuruddin’s novels knows that he is always telling stories that have women at their center, and that his women are not the passive objects of his writing but central, vital subjects in the brilliantly imagined, fully realized, magical world of Nuruddin Farah. Indeed, his first novel, From a Crooked Rib, depicts the life of Somali women so compellingly that the Nigerian novelist Buchi Emecheta once wondered out loud if it could really have been written by a man. She must have been kept wondering ever since by so many Farah women.

In Maps, his 1986 novel, there is Misra, the Ethiopian maid who raises Askar, the Somali protagonist, a refugee from the 1977–78 war between Ethiopia and Somalia in his native Ogaden. Misra is not Askar’s kinswoman, not even his countrywoman, and, as a foster parent to an orphan, she is and is not his mother: but her life is tied up with this young man whom she has raised, her love for him running against the loyalties to people and nation which are the source of so much bloodshed and division, but which are also at the heart of Askar’s identity. In the first chapter, addressed to Askar (but perhaps, the novel’s ending suggests, in a voice Askar himself is ventriloquising), Nuruddin Farah writes: “The point of you was that, in small and large ways, you determined what Misra’s life would be like the moment you took it over.”

What follows is a wonderful portrait of a bond between a mother and a child, told with enormous respect for her love, and for her own insistence that, despite all that is done to her because she is woman, she is glad to be a woman. We know she is glad to be a woman because she says so. When young Askar wakes one day with blood on his sheets, he responds to Misra’s suggestion that he has begun to menstruate with an angry “But I am a man.” Maybe, he suggests later, he is sick, should see a doctor.

She didn’t like his explanation. “It means you prefer being sick to being a woman.”

“Naturally,” he said. “Who wouldn’t?”

She said, “I wouldn’t.’’

But, as I say, Misra is one among a multitude. Throughout the extraordinary trilogy that he called Variations on the Theme of an African Dictatorship—in Sweet and Sour Milk (1979), which won the 1980 English-Speaking Union Literary Award, Sardines (1981), and Close Sesame (1983)—there are so many uncommon women: Margaritta, in Sweet and Sour Milk, who leads us into the world of clandestine resistance to Somalia’s dictator, the Generalissimo (who is not named in the novel by his real-world name, Siyad Barre); or Medina, in Sardines, “as strong-minded,” Nuruddin says, “as she was unbending in her decisions,” who leaves her husband, a minister in the government, to raise their child, Ubax, alone. Medina is protecting her daughter from the insistence of her mother-in-law, Idil, that Ubax be circumcised. She is a cosmopolitan, who amuses her daughter by reading her Chinua Achebe and the Arabian Nights in her own translations, a member of what Nuruddin calls “the privilegentsia,” who speaks “four European languages quite well” and writes “in two.” But she is also secretly working to end the dictatorship.

Medina is joined in Variations on the Theme of an African Dictatorship not only by her precocious, demanding daughter, Ubax, but also by such splendid creations as her mother Fatima bint Thabit, a Yemeni traditionalist; by Idil, her authoritarian mother-in-law; by Sagal, athlete and revolutionary; by Amina and Ebia, Sagal’s friends. The trilogy of Sweet and Sour Milk, Sardines, and Close Sesame is a powerful assault on dictatorship and a powerful indictment of the oppression of women, and the particular forms it takes in Somalia: but it is also a celebration of women’s agency.

The obvious centrality, in Farah’s work, of the suffering of women and their agency is, I think, a reflection of what is deepest in his political argument, which is his recognition of the intimate connection between the dynamics of power in the family . . . and the broader politics of states and nations.

If I seem to be belaboring a point, it is not because I find it surprising that a man should write convincingly about the lives and interests and concerns of women. Writing is always more about identification than identity: the work of the imagination is never simply to express our selves. Nor, despite what many would assume, is a man’s preoccupation with the situation of women especially surprising in Africa: Things Fall Apart, the novel by Chinua Achebe that thrust modern African writing in English onto the world stage, is, in part, a novel about the tragedy of men who do not respect the feminine in nature, in their wives and mothers and daughters, and in themselves. Nuruddin Farah’s treatment of women’s lives is not remarkable because he is a man; it is remarkable because of the power of its moral and literary achievement. And the obvious centrality, in his work, of the suffering of women and their agency is, I think, a reflection of what is deepest in his political argument, which is his recognition of the intimate connection between the dynamics of power in the family—in relations between husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, parents and children, uncles and aunts and cousins, one generation and another—and the broader politics of states and nations. A society that is filled with contempt for women or children or the old, he suggests again and again, cannot have a healthy politics: and the poisonous, murderous struggles that have overtaken his own Somalia have their beginning, he seems to argue, in the struggles of family life. Farah is not the first feminist to have grasped that the personal is political; but he is, in my view, the African writer who has given this thesis its most persuasive imaginative demonstration.

It is important, therefore, that Nuruddin Farah’s world is also full of intensely realized representations of love and loyalty: in Secrets, the most recent of his novels, there is the long love affair between Damac and Yaqat, mother and father to Kalaman, the novel’s central figure, two people held together in a horrifying fatal secret that is both the tie between them and the greatest threat to their happiness. And there is the extraordinary relationship between Kalaman and his grandfather, Nonno, each of whom has named the other; theirs is a relationship that survives from the child’s birth to the grandfather’s death despite the same secret, which also stands between and binds them.

Equally memorable for me is the wonderful love of father, son, and grandson in Close Sesame: with Deeriye the grandfather, Mursal the son, and Samawade the grandson, locked together in a bond between the generations that is cruelly destroyed by the moral demands of life under dictatorship. Not only is Close Sesame a powerfully moving celebration of family across the generations; it has also given us, in Deeriye, the most fully realized picture that I am aware of in English of the interior life of a devout Moslem—indeed, one of the richest representations of a prayerfully devout human being I have ever read. Most Somalis are raised, as Nuruddin Farah was, as Moslems; as a result, the act of imagination here will probably not receive the same attention as the manner in which he has found his way into the minds of so many imaginary women. So, in celebrating the powers of his imagination, we should perhaps notice, too, that Nuruddin Farah, though raised as a Moslem, is not himself devout: he does not claim, even when it would advance his interests, to be so. One of Farah’s many literary admirers is Salman Rushdie, who must, I suspect, be especially admiring of Nuruddin’s capacity to represent respectfully an Islam that is no longer fully his own.

*

Nuruddin Farah, whom we honor today, was born in Baidoa in 1945, but moved at the age of one to what was then the British-administered Ogaden, where his father was a translator. When the British departed from the Ogaden, they left its many Somali inhabitants to the Ethiopians, creating a region of conflict that was to smolder always and burst, from time to time, into the flames of Somali-Ethiopian warfare over the next four decades. In 1963 his family moved to Mogadiscio during one of these wars, one family among a million refugees over the years driven by these conflicts from the Ogaden. He went to university in Chandigarh in India (choosing it over an offer from Wisconsin), and published that first novel, From a Crooked Rib, in London in 1970, at the age of twenty-five, becoming, with that work, the first Somali novelist—though, of course, by no means her first great literary figure, since he was raised within a tradition of oral literature that is among the richest in the world. The Mogadiscio in which he grew up was a densely cosmopolitan product of waves of political and cultural colonizers: Italianate architecture, Islam and Arabic civilization, the English language, all embedded within a Somali culture. Nuruddin speaks not only Somali but also Italian, Arabic, Amharic (the language of Ethiopian rule, from the days in the Ogaden), and, of course, the wonderful English in which he has written his eight novels and almost all his work.

In 1974 he left Somalia to begin a period of nomadic peregrination of a sort that would have made sense to his Somali ancestors, even if he has carried it out on a larger scale, living in Europe, North America, and Africa. In 1976 he published A Naked Needle, a novel that caught the unfriendly eye of Mohamed Siyad Barre, Somalia’s dictator. He was planning to return home from Rome, and had called his brother to arrange to be collected at the airport, when he learned, from his brother, that Siyad Barre was angry with him. What began as a weeklong postponement of his return, to give the Generalissimo time to cool down, turned into a twenty-twoyear exile, which ended in 1996, five years after Siyad Barre’s departure had plunged Somalia into the crisis from which it has still not emerged.

In the meanwhile Nuruddin has lived in Italy, Germany, Britain, the United States, Uganda, Sudan, Ethiopia, and Gambia; his latest place of residence is Kaduna, in northern Nigeria, the home of Amina, his wife. But next year they will be packing their tent again and moving to Cape Town. In 1986 he was kicked out of Gambia for accusing President Sir Dawda Jawara of being more interested in golf than governing. (“Stupid of me,” was his laconic comment to an Associated Press journalist.) In Uganda, in 1990, he got on the wrong side of President Yoweri Museveni, then chairman of the Organization of African Unity, accusing him of failing to mediate the war in Somalia. “Museveni was inept,” Nuruddin said with the special tact he reserves for presidents. After Museveni denounced him at a news conference, Nuruddin took the hint and moved to Ethiopia. Nuruddin Farah has been thrown out by more African countries than most people have visited; he has visited more than most people could name.

I wish I could explain to you how a man who was deprived by exile of his people and his family has kept his people and his family—and the idea of family and people—alive in the crucible of the imagination.

I wish I had time to tell you more about his writing: about the thoroughly original way his characters live as much in their dreams as in their waking lives; to describe how his novels are morally serious without being preachy, or how he teases you by writing of events that seem magical but also always have possible unmagical explanations; to show you the richness and power of his prose. I wish I could explain to you how a man who was deprived by exile of his people and his family has kept his people and his family—and the idea of family and people—alive in the crucible of the imagination. But these, fortunately, are things I don’t have to tell you about, because you can read him for yourselves: all of them are there in Secrets, a work which proves that a master of the novel is still growing in his craft. Read it. I promise it will reward your reading: but I also have to warn you that you will end up having to read the rest of his work.

I know I am keeping you from the man himself, but I should like to say one more thing in closing: Nuruddin is a man with an extraordinary gift for friendship, and friendship is something that we should honor more than we do and give thanks for when we can. But Nuruddin is also, as I have been telling you, a magnificent novelist, and we should honor and be grateful for that, too. I have been struggling as to which of these gratitudes I should express in closing. But I realized today that I do not have to choose between thanking him for his novels and for his friendship. For his novels are a friend’s gift: and he has given them, as a gift of friendship, to the great company of men and women now reading his novels around the world.

Norman, Oklahoma

October 29, 1998

Editorial note: This encomium was first published under the title “For Nuruddin Farah” in World Literature Today 72, no. 4 (Autumn 1998): 703–5.