Quinta del Sordo

I wish that I could find myself asleep tonight

in a house on the banks of the Manzanares,

the river that begins in the Sierra de Guadarrama

and flows through Madrid before joining

the Jarama, the Tagus, and then emptying

four hundred miles away into the Atlantic,

the house christened Quinta del Sordo,

the Villa of the Deaf Man, so named for the owner

who, in silence, walked its grounds

during the Spanish uprising of 1808

and the Peninsula War, selling the home

to the artist Goya in 1819, who, deaf himself,

began to paint directly on the plaster walls,

only his maid and lover, Leocadia Weiss,

accompanying him, her dark hair veiled

in Goya’s painting, one of the last

of the sequence throughout the home,

the elder Goya rumored to be mad

at seventy-two, resigning to the country

from the court in Madrid, the river cutting

the countryside like a slash from a French bayonet,

and Goya’s hand rising to the plaster walls,

his brush tip wet with oils as Leocadia

poses in a funereal dress, Goya placing her

in the painting beside what is believed to be

a burial mound, and though I do not know

what I would dream there in that home,

I would like for Goya’s dog to guide me,

the dog of whom only his black muzzle

and head are seen rising above the ochre earth

that divides his painting horizontally in two,

the context unknown as to whether the dog

is sinking into the earth or raising his head

cautiously from his den, and I imagine him

nudging me, asleep in the lone bed centered

in the upstairs room, the dog, not tripping

over his paws or shaking his coat, but placing

his chin on my thigh with the same pressure

with which someone might wake a child,

or lower the barrel of an adversary’s gun,

and without a whimper the dog would lead me

past each painting, past Saturn Devouring His Son,

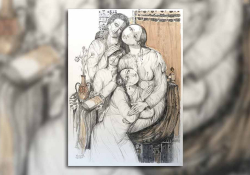

past The Fates, Two Women and a Man,

past Duel with Cudgels, the background

of all of the paintings a kind of mottled gray,

less dark than the dog’s sleek fur, wet from a swim

perhaps, his coat dark as the night sky, made darker

by the piercing of stars, their pin-prick light falling

on the Manzanares, on the banks of which

the dog and I stand, his pearlescent eyes round

as the moon glinting on the river’s wet sand.