Two Poems from the Hindi

For more, read Anita Gopalan’s essay on translating Chaturvedi’s poetry into English.

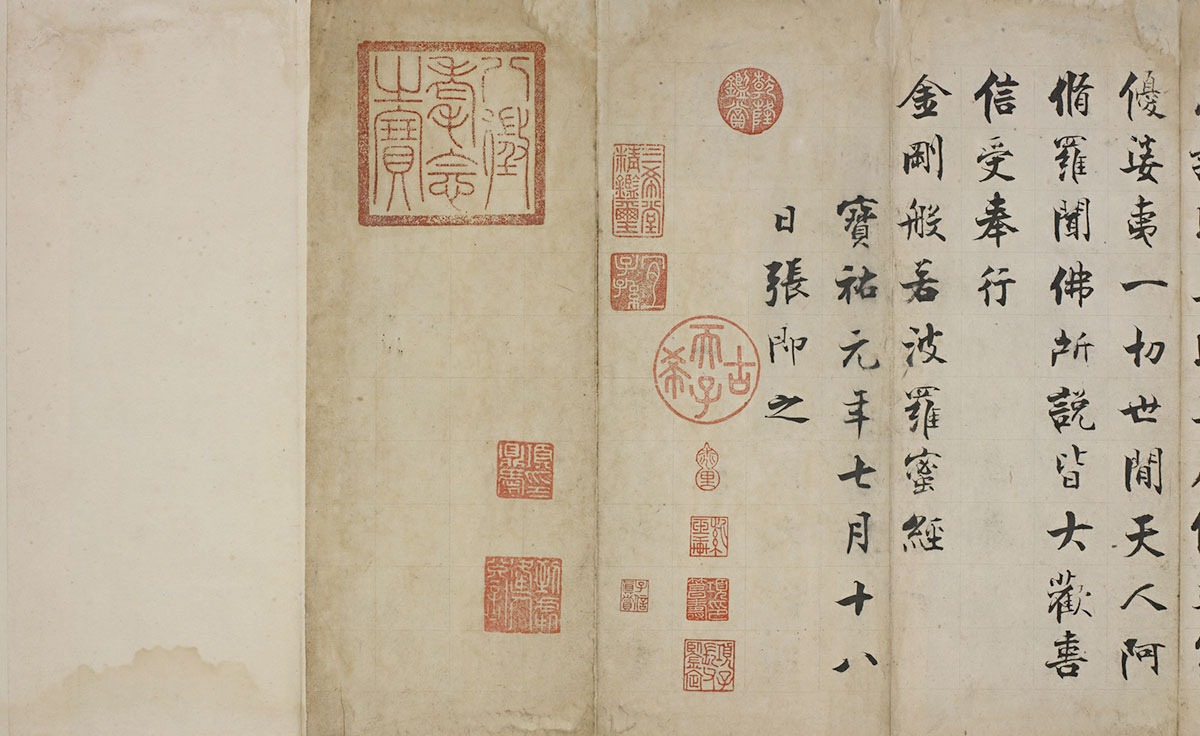

The Tongue of Kumārajīva

Kumārajīva lived in the fourth century. The man who rendered the first known Chinese translations of the Buddhist Sutras from the Sanskrit and local Pāli. Extensive translations. It won’t be an exaggeration if we say that of antiquated history, he was only the greatest known translator. (Although there had been many translators before him, their names could not reach modern times. Even if they reached, they would be little known.)

It is said that his translations were so authentic, so very faithful to the original, so tightly coupled to the truth that when he died and was being cremated, the entire body burnt and became ash, but his tongue withstood the flames and did not burn.

With that tongue then Kumārajīva had, orally by virtue of spoken words, translated the Sutras into Chinese.

After all these years, reverse-translations of the translated texts are taking place. The original Sanskrit-Pāli treatises have been lost for good, but in the Chinese all of that has survived. Today we get to learn many things about Buddha based on English and Hindi-Sanskrit translations from Chinese.

So the tongue of Kumārajīva is present in much of what we know about Buddha today. Despite that, we know nothing about Kumārajīva. In the history of tongues, therefore, the tongue of the translator is the most selfless.

The tongue of the translator, which even fire cannot summon courage to burn.

You kill the truth, the translation of truth will come forth. You destroy the translation, still the tongue-sized piece of truth will persist. Eagerly-restlessly, hopping and bouncing, it will continue to speak its words.

My Language, My Future

Outside the city in the garbage dump under the bridge

The most senile poet of my language chews bread dunked in tea

This man invented poetry even before Afzal*

All three hundred and thirty million Gods live in his beard as lice

The hairs on his body are all his unwritten poems

He furrows words in air with his fingers

In this way, he writes to his past every night a letter

Which is lost even before an envelope is found

Once before dying

At least once

He hopes that he’ll recall the face and name of the woman

Who at one time slept with his book of poems

Pressed under her pillow

* Author note: Afzal refers to Afzal Ahmed Syed, the Pakistani Urdu poet, and his poem “I Invented Poetry.”

Translations from the Hindi

By Anita Gopalan