Translating Norway’s Love of Literature

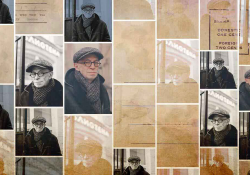

A Conversation with Don Bartlett

In Norway, many bookstores carry a wide variety of translated fiction, noticeably more than one might see in a UK or US bookstore. Don Bartlett and other translators of the Norwegian language work on translating the culture of Norway into English. I spoke to Bartlett about the importance of cultural knowledge in translation, what it’s like to translate the variety of literature in Norway, and what he’ll be working on after he finishes a Danish thriller.

Perhaps in reading Norwegian works we can pick up whatever it is that seems to so influence the Norwegian populace to read other cultures.

Sarah Smith: How did you first learn Norwegian? How was the process different from the other languages you've studied?

Don Bartlett: After studying German at university, I worked in Austria, Germany, and Denmark as a teacher. Learning Danish was different in that I had to learn it from scratch in the country. My method for learning was an all-out attack on listening, reading, and speaking; I had a grammar book nearby to check at all times. This process was different from previous language-learning experiences as I was surrounded by language all the time, I didn't go to formal language classes, and I determined the “syllabus” myself. It was real-life learning, if you like, and much more enjoyable. At the same time, I studied English and linguistics at Aalborg University and began to read Norwegian and Swedish. I am still learning, of course.

SS: I saw that you translate not only Norwegian and other Scandinavian works but from German and Spanish as well. Are there any challenges you’ve found with translating Norwegian literature that differ from the other languages you work with?

DB: What I have done in German and Spanish literature is minimal, so there isn’t really enough data to compare. But I have grown into translation from Danish and Norwegian and developed. I suspect the same would have to happen with any other language.

You have to understand the second language culture from the inside to know what you are describing, and you have to see your own culture from the outside to be able to describe it.

SS: Have you traveled to Norway? How do you think spending time in the countries and cultures whose languages you work with affects your translations?

DB: Yes, I often travel to Norway and Denmark, every year at various times. Knowing what life is like in these countries is essential for translation. You have to understand the second language culture from the inside to know what you are describing, and you have to see your own culture from the outside to be able to describe it. I think it would be difficult to do a proper job without having lived in the cultures of second languages. So many of the problems in translation come from cultural differences.

SS: When I was in Oslo this summer studying Norwegian literature (in English translation), I felt a sort of coziness in both the city and the literature—and by that I mean a calm quiet, in walking near the Aker River or in seeing life from the eyes of Mattis in Vesaas’s The Birds. Perhaps from your translation work on the short-story anthology Leopard VI: The Norwegian Feeling for Real, is there any "vibe" you get consistently in working with Norwegian literature that’s different from your work with, say, German literature?

DB: The impression I have of Norwegian literature is that it is very varied, as you will have seen in the anthology. Varied and full of vitality. The anthology includes a wide range of writers, a wide range of styles and moods, and in the nine years since its publication the range seems to have increased.

SS: The Paris Review’s short piece (2012) on Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle mentions that in the text, “the narrator slipped into clichés, [which] made him seem that much more real and single-minded.” What was it like to translate something with such a personal and distinct voice as an autobiography?

DB: Daunting for a host of reasons, and daunting, as you suggest, because you are providing the English voices of people who really exist. For the first novels, I sent the draft translations to Karl Ove to make sure I had found a tone in the book that he felt was representative.

SS: Scandinavia is known in recent years for its crime fiction, and you’ve translated both crime fiction, with Jo Nesbø’s books, and more “ordinary” fiction, like the short-story anthology and a few of Per Petterson’s books. Did you encounter any challenges with crime fiction that you didn’t with other translations? Which did you enjoy more?

DB: Yes, there are challenges with crime-fiction novels. Thinking about Jo Nesbø, I can remember being absorbed by codes that work well in Norwegian but don’t in English, titles that are layered with associations, puns, and humor, fiendish weapons, technical detail, slang, dialect, names of ranks and police organizations, and maintaining a certain style. I enjoyed all of this enormously. I still enjoy translating crime fiction and prefer, if there is a choice, to have a balanced diet of both crime fiction and general fiction.

SS: What do you think it is about Scandinavian cultures that they foster crime fiction so well?

DB: There is a crime-writing tradition in Scandinavia, and Scandinavians read crime fiction from all over the world. They also have their own models, like Maj Sjöwall and Per Wahlöö. Scandinavian crime novels bring an exotic landscape (fjords, volcanoes, geysers, mountains, forests, sea, small islands, ice), strong women characters, solid plots, atmosphere, myths—all set in small countries with welfare states that many consider enviable. Add to those characteristics problems that all developed societies face: immigration, a widening gap between rich and poor, the power of the press, the power of banks, etc. There is a lot to like; there is a lot that readers don’t know about Scandinavia. And there are a lot of writers from each of the Scandinavian countries with a slightly different take on the genre. Since some English-speaking writers are setting their novels there now, the area must have something special!

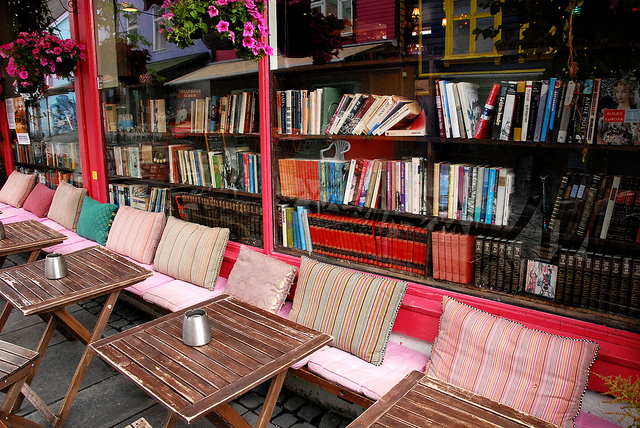

SS: The Norwegian government funds NORLA, Norwegian Literature Abroad, to aid in spreading Norwegian literature to readers of other languages. When I studied in Oslo, I also noticed significantly more international works in bookstores—even in secondhand stores—than I normally do in American bookstores, and even saw an entirely French bookstore. Have you noticed in your translations of Norwegian literature or in traveling to Norway a difference in the way Norwegians relate to literature and their literary past than do other nations?

DB: It is significant that bookshops in Norway have a wide range of translated fiction. I don’t know what the percentage of translated literature is compared to the home-grown variety, but it will be a great deal higher than in the UK, for example, despite the recent boom in foreign crime fiction. Actually, this is true of most European countries. UK bookshops can draw on a wealth of anglophone literature (from the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, Africa, etc.) but until around 2000 didn’t pay much attention to translated fiction.

My view may be skewed because I always meet people involved with literature in some capacity, but my impression is that there is huge interest in literature in Norway. The Easter crime book and the new publications in the autumn are always greeted with immense enthusiasm. And in terms of the broader impact Norwegian literature has had, Norway punches well above its weight.

SS: Having worked with the literature of several countries, what can you tell us about the publishing process in Norway?

DB: I can say that Norwegian publishers (and the Norwegian Embassy and NORLA) look after their authors very well. They are given time and respect and are supported financially.

SS: Which yet-to-be-translated Norwegian authors do you think should be next in line for translation?

DB: I wouldn’t like to say—I am kept so busy by current novels that my own reading has fallen behind. I am looking forward to reading Trude Marstein’s Hjem til meg and Roy Jacobsen’s De usynlige. They haven’t been translated yet.

SS: What current projects are you working on?

DB: I am co-translating a thriller by Elsebeth Egholm from Danish with a working title of Dead Souls and, because an earlier co-translation has overrun, a Norwegian novel entitled Borders by Roy Jacobsen. In late March I will start the fourth book in Karl Ove Knausgaard’s My Struggle series.

Don Bartlett lives in Norfolk, England. In 2000 he studied for an MA in literary translation at the University of East Anglia, Norwich, and since then has translated children’s books, crime fiction, and literary fiction by authors such as Stian Hole, Jo Nesbø and Karl Ove Knausgaard.

Sarah Smith is a WLT intern studying writing at the University of Oklahoma. She hopes to someday write a book high school students will be forced to read. When she isn’t writing, she serves as a volunteer barista in a nonprofit campus corner coffee shop.