When Language Meets an Ecosystem

In the following essay, the authors look at poets and visual artists who use language in ways that blur the line between disciplines, with a particular emphasis on the environment.

What happens to language when we place it in landscape? Does it admit our isolation from physical life, point to the power system faltering? Humans have named land as a means of claiming it, branding it, or romanticizing it, and when we catch ourselves at it, we may reflexively hurt or do penance in long speeches. Can language’s synesthetic origins in landscape be salvaged? The poet C. D. Wright maintains, “. . . words are golden as goodness is golden. Even the humble word brush gives off a scratch of light.” Language, for sure, continues to live, and meeting it in the landscape unmediated by the entirety of its usual authority opens possibility.

Language, for sure, continues to live, and meeting it in the landscape unmediated by the entirety of its usual authority opens possibility.

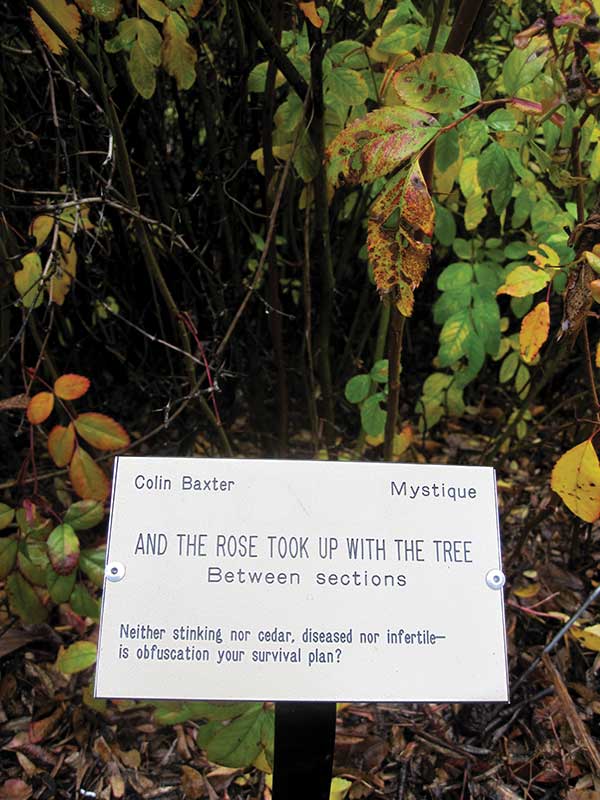

In 2012–2013 we installed language, as signage, into the University of California Botanical Garden at Berkeley, part of the exhibition Natural Discourses: Artists, Architects, Scientists, and Poets in the Garden. Our project, “Botanica Recognita: Signage to Facilitate a Greeting,” confronted the most authoritative language in the garden, the naming of plants. Collaborating with the gardeners, whose decades of experience had rendered some interesting relationships with particular plants, we reworked the signs for twenty-five trees, shrubs, and perennials. We wanted to so animate the language that it would be a portal of experience for the reader, in the present moment, greeting each plant, in a shared human-nonhuman habitat.

In our research, we often uncovered the authoritative lie. The so-called stinking cedar, for example, was neither odorous nor a cedar; it had grown to more than twice its standardly described maximum height and was not infertile, as documented for its species—maybe, dreamed the gardener, because of the rose entwined through it, which he could not bring himself to prune. We renamed it “And the Rose Took Up with the Tree.” Our search to see what language can do off the page, in our dynamic physical environment, led us into creating more site projects and discovering the following works that chart ways of animating language in ecosystems.

Canadian poets Stephen Collis and Jordan Scott have created a conceptual poetry project that tests the limits of language and the position of humans in the environment. Their inquiry begins when they place a copy of Charles Darwin’s book On the Origin of Species in five different bioregions in British Columbia and let it sit there exposed to the elements. After a year they go looking for the books, they photograph them, then co-write their own book, Decomp; in it they track process, theirs and nature’s. Their simple experiment yields a wealth of discoveries by complicating the usual subject-object relationship of humans and nature. As Collis states at the outset, “I’m not going to put the natural into the text, I’m going to put the text into the natural world and see what happens to it.”

Each of the five sections opens with photos of the decomposed text, revealing the extent of the transformation and how the effects are particular to each bioregion. Their writing, which creates a further decentering by being a collaborative text, does not tell a linear narrative of their experience. Forms shift from verse to prose, quotes (by friends/guides and leading theorists, including Blanchot and Agamben), glosses, and footnotes. The tone shifts as well. At times the text sounds like a scientific logbook, at others, philosophers’ meditations or experimental poetry. Process is foregrounded, evident in the book’s ragtag quality, full of gaps and contradictions between culture and nature.

In an interview with Jillian Harkness, the poets give their reason for choosing On the Origin of Species. “Going back to Darwin was a little like going back to the ‘source’ for writing about nature and our un/belonging there.” Their treatment of it can be taken as a critique, composting his theories and categorizations, but more telling is the way it enacts Darwin’s belief in the role of chance in natural selection. As Elizabeth Grosz points out in her introduction to Becomings, “survival of the fittest” is often mistaken to mean dominance in one particular environment, but what Darwin is actually getting at is an organism’s ability to adapt in a continually changing environment.

For Collis and Scott, the greatest discoveries come with the completely decomposed book found in the forest. Until this last section of Decomp, each section included a transcription of words gleaned from the eroded text, boxed off and titled “The Readable.” Now no words are discernible; the box is blank. The poets, and readers, face the gaping silence of the forest. Provisional (decomposing) language gives way to a felt experience of impermanence: “What is decomposition if not the certainty of change,” they write, then a few lines down, “I’m not sure what I’m changing into.”

South African interdisciplinary artist Kai Lossgott types and engraves language into leaves, some the shape of his own hand, with veins, even palmate. The text “wait for me and witness / you, who wants everything now / that nothing worth waiting for / is complicated” first appeared in his monograph, talking to the tree outside my window while I sleep. The typewritten lantana leaf entitled “witness” raises the question who witnesses what, or what witnesses whom, and the potential for communication between word and living object. Through improvising the text on the leaves, it becomes more abstract as he transposes it off the page into living tissue, punched-in to the point of unreadable near-destruction. Light shines through the leaves, mounted in light-boxes. Light gave life to the living leaf by activating photosynthesis, which in turn gives us oxygen. The artist points out that our attempted intimate conversations with the planet’s living systems often leave a record in the form of scars.

Our attempted intimate conversations with the planet’s living systems often leave a record in the form of scars.

Language, like DNA, is a code that stores memory, and the engraved leaves, which Lossgott collected in suburban Cape Town and Johannesburg, suggest perhaps a memory of a relatively recent past (in biological terms) when humans, like their evolutionary ancestors, lived in trees. What remains is something American scientist E. O. Wilson calls “biophilia,” an innate affinity with other living systems. Lossgott states in an interview with the South African curator Cecile Ludolff, “I write and draw symbolic love poems to nature on plant leaves, because the writing of a love poem is an act of bridging loss. It is a way of coming to terms with the world we should have and could have, but which seems ever out of reach.”

Canadian-Icelandic interdisciplinary artist a rawlings spent an artist’s residency in Queensland, Australia, trying to establish communication with that landscape. She named her prolific project Gibber, a word that carries the sense of human language in its beginnings, protolanguage, communicative of the experience of the body and desire, and language of a doubtful intelligence as it leaves the mouth and arrives in the world.

rawlings placed glass vials, stoppered sampling tubes, into the ocean surf. Each contained one textual signifier: Place. Island. Land. Line. Landscape. Name. Song. Word. In the photographic documentation (www.gibber.com), the vials toss in the tide, writing a sound poem and a visual poem on the beach. One of several photographic elements of her project (which lives only online), “Vialence,” says rawlings, gives in to “a moment when the urge to identify, name, possess grips the body.” rawlings put the language most readily at hand, her first language, the nonnative, bottled language of the colonizers here, back into play with the ocean across which they came.

Language and ecosystem collide. Her vials float, and turn, and sink in the shallows like seaweed and are stranded on the sand. There’s our language, behind glass in its habitat, creating a poignant (non)conversation before our eyes. In an interview with Gary Barwin, she says, “Consider the (ages-old) impacts of soundscape and landscape on linguistic formation—on letter forms, syntactic construction, pronunciation. Imagine, too, the importation/introduction of languages into foreign ecosystems. With the slip of a tongue, what loss?”

Choosing listening as her ecopoetic practice, rawlings documents the marks and traces of nonhuman bodies—balls of sand left on the beach by crabs, the growth/architecture of local plants, the congregating patterns of barnacles on rock, the flight of a bird. She speculates that this is language also, or linguistic, possibly communicative, acts, the asemic writing of an ecosystem: “How do we define ‘writing’?” she asks. “Does it need to be an act composed by a human entity? Does it need to occur with a certain kind of material, on a certain material, within a certain time frame?”

She followed the repetitions of nonhuman forms of movement as the impositions of one thing on another, like ink on paper. At stake for rawlings is “how to ethically read, converse with, collaborate with, and/or interpret nonhuman entities.” That’s a project that can’t be realized through speech as a desire to possess, or using inherited semantics, but rather by synesthetic attention. If she studied the marks made by nonhuman life long enough, she thought she might be able to decode them.

Human language frustrates as a means to describe place. Artist Tacita Dean, at the end of her book Place coauthored with Jeremy Millar, writes of her failure to locate/articulate her subject. “Do I describe where I am? Do I describe the weather, the birdlife, the smell? [Place] is best imagined through the senses. . . . I played with many ideas about place for this book, but in the end I realized it can only ever be personal.”

One of the projects presented in Place is British artist Adam Chodzko’s “Better Scenery, 2000.” Chodzko signals the language-ecosystem problem by “misplacing” interpretive signage in landscape locations. A large sign in the Painted Desert of Arizona explains how to get from central London to the O2 shopping center car park off Finchley Road, in north London, and the sign there provides directions from Flagstaff to the Painted Desert. Photographs of the two signs in their contrasting ecosystems constitute a diptych at the Tate Museum, London. Place is exotic when elsewhere, other. The simple language of giving directions leads the reader along and pulls the rug out from under itself, constructing a failure to engage the reader’s body in the present time and location—until the last line of the directions, which in both locations reads, “Here, in this place, is a sign which describes the location of this sign you have just finished reading.” A familiar loop of linguistic remove/displacement occurs—after all, a common engagement linguistically with site is as a tourist writing the postcard: Wish you were here.

These language-ecosystem collisions occur in a field overgrown with desire and escapist fantasy.

In “Better Scenery, 2001,” signs are located outside a car factory in Turin and in a forest in Cumbria, England. In “Better Scenery, 2002,” the signs are in a field in Fargo, North Dakota, and in the branches of a tree outside Cubitt Gallery, London. These language-ecosystem collisions occur in a field overgrown with desire and escapist fantasy. In another project, Chodzko placed a pencil drawing of a forest in a sex-contact magazine with the words, “Please will you join me here?”

Language reaches toward—and then may represent our situation in the world problematically, insufficiently. Brenda Hillman, in an interview with Angela Hume, speaking of the complexities of our relationship to the environment, warns against timid poetics at this moment: “The problem for the poet is always how to present these things in a nondidactic and imaginative way,” she says. “For me, the situation calls for both an intense, unpredictable poetry and an imaginative activism.”

Japanese American poet and translator Sawako Nakayasu’s work epitomizes unpredictability in language and interactions with other beings. She slips between fact and imagination, and from one art medium (and language) to another, producing work in various iterations, with improvisations. The Ants, composed of seventy-nine short prose poems, is part of her ongoing project called Insect Country and so far has included several performances, short films, two days of live writing in a gallery, and the start of the “no collective”—all equal parts of the investigation.

In the poems, ants overrun her linguistic positions: they arrive in human mouths and bodies, they make their home in a freshly baked carrot cake, an ant writes with its rear end, some call out the rhythm: “and and and and and and and . . .” and so on. Scale and point of view shift continuously, and we lose our footing in a dreamlike looping of subject and object. As she says in her “Working Note” on the University of Arizona website, “I work mostly in poetry because it claims to be neither fiction nor nonfiction, because it acknowledges the gap between what really was or is, and what is said about it.” Noticing the gap means resisting language, and by delaying naming, Nakayasu opens the possibility of something else to occur.

Our favorite piece of language since we began researching this article is artist Ruth Sacks’s skywriting, in 2005, over Cape Town: “Don’t Panic.” It’s a congenial gesture that stops us in our tracks, alters the physical environment, and is altered by it. As with the other projects, it demonstrates how language can follow feeling to the edge—to a scary, reciprocally dynamic situation that is the present. There, language’s nonauthority can decompose our righteousness, our singleness, even as landscape continues to soothe us and draw us into collaboration with what is at hand, what just spoke, unfathomable, ephemeral. This is where language is alive and takes into account the live other. It may falter, slip into silence or gibberish, but it’s sounding out the new cultural attention to a very old, complex relationship to habitat. These artists and poets show language engaging in shifting contexts and occurrences, bravely going forth not knowing where it’s going to lead, but it meets the world.

This is where language is alive and takes into account the live other. It may falter, slip into silence or gibberish, but it’s sounding out the new cultural attention to a very old, complex relationship to habitat.

San Francisco