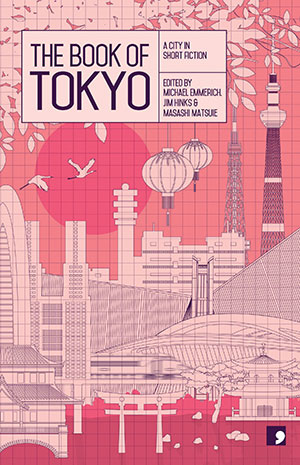

Editor’s Pick: The Book of Tokyo: A City in Short Fiction

Jim Hinks, Masashi Matsuie & Michael Emmerich, eds. Manchester. Comma Press. 2015. ISBN 9781905583577.

This new collection of short stories by Japanese writers, all set in Tokyo, opens with a monster on a killing spree aboard Tokyo’s train system as it loops twice around the city center. Though the stories that follow are less fantastical, the city’s train system is one of the consistent concrete markers of Tokyo that runs throughout the collection.

In his introduction, Michael Emmerich (see WLT, May 2010, 15–17) describes the collection as drawing what may be a more conceptual than physical vision of Tokyo, so it isn’t any surprise that each story doesn’t devote its greatest attention to physical descriptions of the city. But Tokyo is more than present enough to justify the book’s title and, in some instances, is rendered vividly, as are the interior worlds of the characters.

The people in these Tokyo stories are declaring their independence, struggling to express themselves, afraid of falling behind, confronting middle age, performing small kindnesses for one another on smoke breaks, grappling with contemporary codes of chivalry, and even wondering whether it makes sense to continue on. Some are visiting pachinko parlors and shopping at the local fishmonger’s. Others are venturing into European-themed coffee shops, listening to Bob Marley in reggae bars, and eating at Red Lobster. They’re zoning out in front of televisions, collecting French literature, and having sex—or not having sex while fantasizing about it obsessively and habitually skipping psychiatric appointments. It is self-analysis that the characters consistently engage in as they work to understand their lives and relationships. Perhaps the monster set loose in contemporary Tokyo is a familiar, global one: angst.

Within this anxiety, though, are moments of connection, for instance a stranger stopping on a train platform to pick up a dropped wallet: “Why is it that people pick up other people’s things? To make a connection? . . . The world is held together with such generosity” (Nao-Cola Yamazaki, “Dad, I Love You,” Morgan Giles, tr.).

Taken together, these ten strong stories by ten different translators provide less a brick-and-mortar description of the city than an intriguing impression of what it’s like to come of age and face middle age in contemporary Tokyo.