Trust in Art

Painting was called “silent poetry.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

Eager to emerge from isolation and encounter art and (safely) others, a writer in Florida takes in Van Gogh Alive at the Dalí Museum and finds a “strange beast” aspiring to be “a form of edutainment, geared for an impatient, digital age, accustomed to overstimulation.”

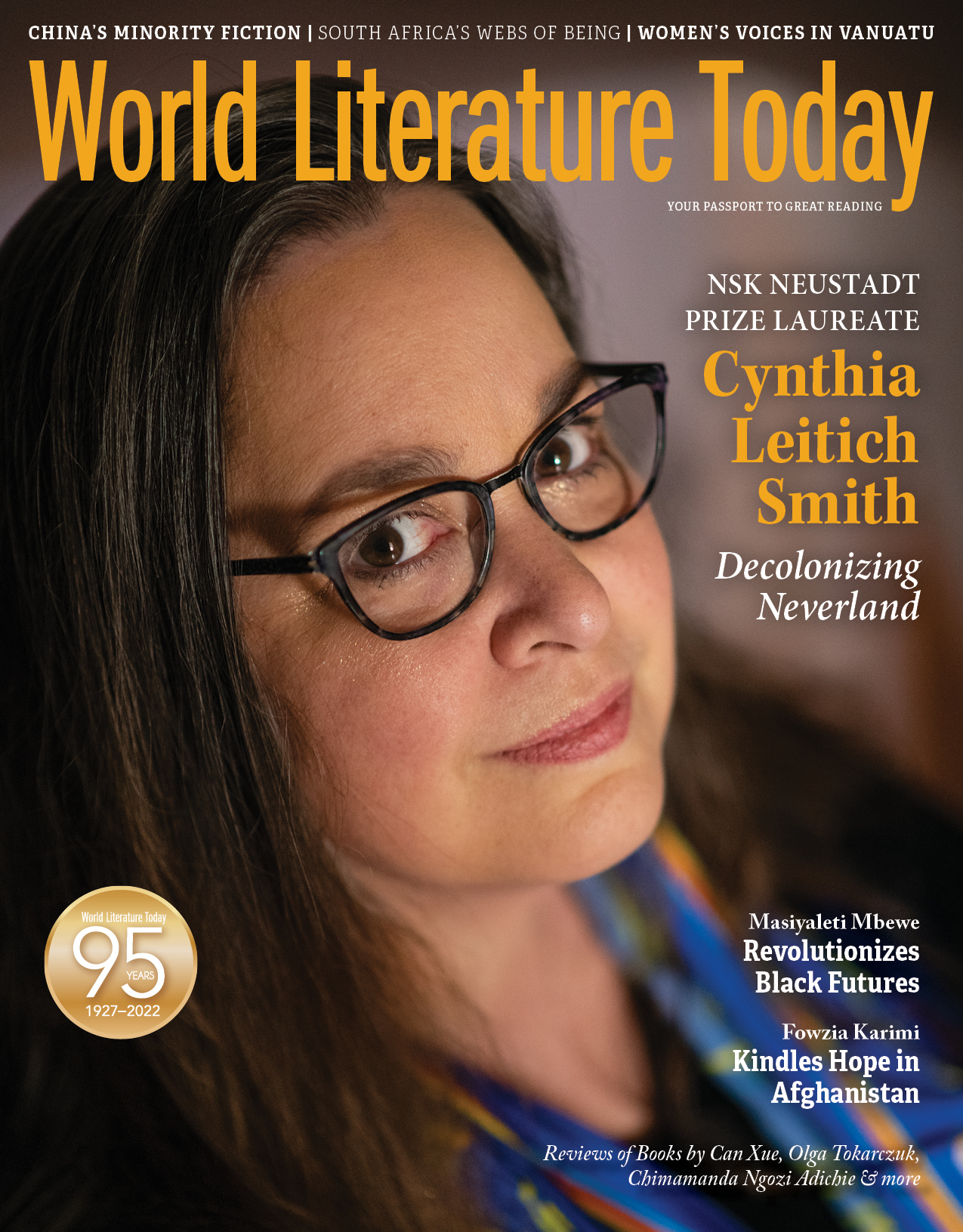

Living in Florida for over a decade, I’ve been meaning to visit the Dalí Museum for a while. When I learned they were also featuring a van Gogh exhibit, fusing art and technology, that was all the incentive I needed to make the four-hour trek to St. Petersburg. The Dalí boasts that it is the first venue in North America, where most of the shows are held, to host Van Gogh Alive. Yet, beginning in 2021 and through 2022, spaces throughout Europe, Asia, and the Middle East are taking turns receiving this wildly successful, hard-to-classify art experience—a total of some seventy cities worldwide, with a few like New York City, San Francisco, Chicago, Charlotte, and Toronto even offering yoga classes within the exhibit!

The only tickets I could find available for the Dalí–van Gogh doubleheader were for 8:30pm. Considering the museum closes at 10:00pm, that meant I had to do something I dislike: rush. So as not to give myself indigestion, I decided ahead of time to split my precious hour and a half evenly between the two greats. In honor of the incorrigible surrealist, the building housing his permanent collection was, suitably, visually arresting and fantastical.

Designed by architect Yann Weymouth, from the parking lot you are greeted by the otherworldly structure: a rectangle with eighteen-inch-thick hurricane-proof walls, from which emerges a giant free-form geodesic glass bubble known as “The Enigma.” Once inside, I savored the deservedly celebrated classics by Dalí that I’d only seen in reproduction, showcasing his playful, dynamic virtuosity: from the hallucinatory The Disintegration of the Persistence of Memory to the technical brilliance of Living Still Life.

I was captivated by my encounter, face-to-canvas, with the late works of Dalí—following his break with the surrealists—who had come to judge the art of his contemporaries as spiritually barren. In 1950 the ever-evolving, ever-curious artist coined the term “Nuclear Mysticism” to describe this phase, preoccupied with the mysteries of science and religion. The monumental canvases on display at the museum from this period are awe-inspiring, in scope and scale. Also rewarding, on another level, were the unexpected pieces from his early years, when the young artist was still discovering his voice and imitating his teachers. The permanent collection is a real eye-opener and a mind-bending audience with a master—made all the more memorable for having been my first museum outing since our global pandemic began!

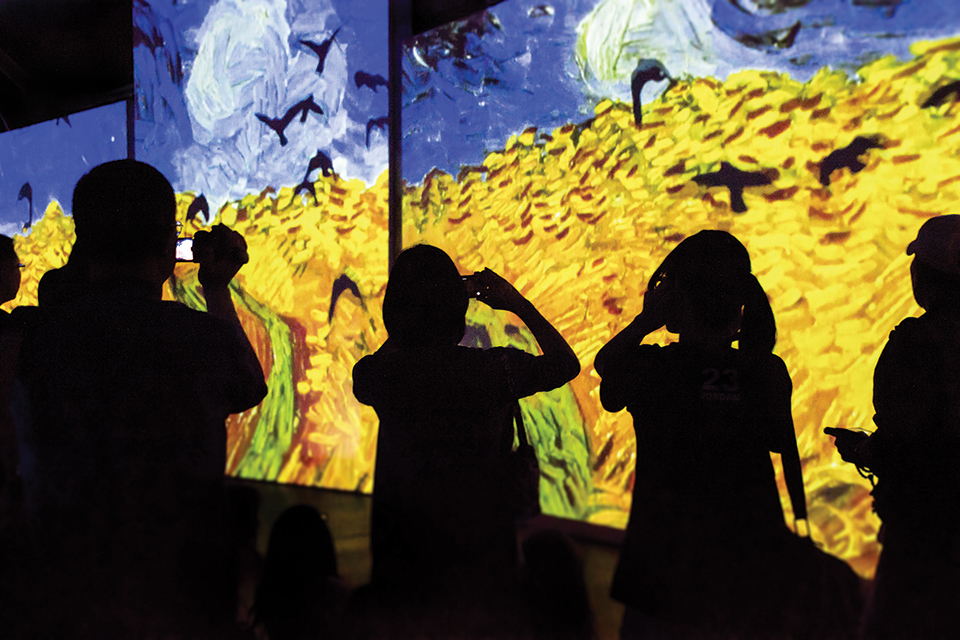

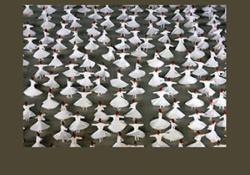

After being cooped up for so long, I admit I was starved for culture and (safe) human contact. Masked up and social-distancing, I was not prepared, however, for the van Gogh “exhibition.” The forty-five-minute experience (ideal timing) is also dreamlike, only more in the sense of a group psychedelic trip, where we the attendees “turn on, tune in, drop out,” letting the sound and light show wash over us. Unlike the Dalí experience, there are no gracefully mounted canvases for the museumgoers to slide up to, tilting their heads to sip and drink in the brushstrokes, all polite smiles and hushed appreciation. For those looking to be fine-tuned by the civilizing influence of Beauty—standing still and reflecting in the refracted light of another’s encounter with the Sublime—the van Gogh presented here is something of a shock to the fragile system. Alone together, huddled in the dark, we are ravished by hundreds of beloved images by the postimpressionist Dutch painter—ecstatic sunflowers, swirly starry nights, moody self-portraits—cast on walls, ceilings, floors by high-definition projectors and accompanied by a musical score, from Ravel to Handel to Thom York and Édith Piaf. It’s an all-encompassing and overpowering, multisensory feast. At times, the already bold and dramatic art comes alive, with theatrical flourish, such as when crows in van Gogh’s atmospheric Wheatfield take flight, accompanied by rousing classical music and punctuated by the alarming sound of a gunshot.

Alone together, huddled in the dark, we are ravished by hundreds of beloved images.

Entertaining as all this might be, riveting even, is it necessary? Is it not enough to quietly admire the master’s soothing irises and uplifting almond blossoms in peace? Are special effects—such as drama, narrative, poetry, even music—not already built into great art? Can we not trust in the sacred communion between art and viewer to tease them out and leave one transported? Do the technical gimmicks, in ample display here, enhance or reduce our aesthetic experience? These are some of the questions that this ambitious production raises, which get to the heart of what art is, and how it should be appreciated.

But the unsubtle Van Gogh Alive is not quite an art exhibition. This strange beast aspires to be a form of edutainment, geared for an impatient, digital age, accustomed to overstimulation. When more is less, visual gluttony and an appetite for sound bites prevail, both of which this audiovisual spectacle caters to. Throughout this glorified Instagram story of the prolific, tragic nine-year career of van Gogh (who began painting at twenty-eight and took his life at thirty-seven), we are also treated to snatches from his letters accompanying the projected paintings, such as: “When I have a terrible need of—shall I say the word . . . religion, then I go out and paint the stars.” A perfect quote for the spiritual-but-not-religious seekers of today.

When more is less, visual gluttony and an appetite for sound bites prevail.

The result is a sense of unearned intimacy with Vincent, the man, but more likely The Myth of the Tortured Artist. Designed by Toronto company Lighthouse Immersive and Massimiliano Siccardi, it’s not unsurprising that the Van Gogh Alive features in Netflix’s Emily in Paris. Attending this event felt more like watching a movie than reading the book. The cynical response to the frenzy with which this show is being received would be that, in the damning estimation of Nietzsche, “most people prefer the copies to the originals.”

The charitable view, however, might counter by suggesting that this immersive experience, which opened during the pandemic, is queerly suited to our bewildering moment at hand. As we emerge from our cocoons, unsteady and blinking in the light, this is precisely the glut of escapist entertainment that we crave: part movie theater, part art gallery, part concert, carnival, and family outing all rolled into one over-the-top, pulsing totality.

But art appreciation is not a passive sport and requires time, care, and work on the viewer’s part before art surrenders its secrets. An original painting grants us access to elusive truths about our self and world by teaching us how to see and feel, differently and profoundly, thus making sense of our unfathomable longings. Great art is transformative that way and also transmits the artist’s perception, vision, and world (inner and outer). Mysteriously, mystically, even, art is a mummification of the spirit of the artist. Which is why something invaluable and ineffable is lost when a living painting is blown up and flattened against a wall. What is lost is the very soul of that painting.

Mysteriously, mystically, even, art is a mummification of the spirit of the artist.

In the final equation, the extravaganza dubbed Van Gogh Alive succeeds in being both overwhelming and underwhelming, leaving us overfed and undernourished. Good art is a conversation that, in silence, carves out a space for itself and for us to inhabit, wordlessly. If one feels stunned and a little hollow after this art assault, it is because we were denied the space to process or talk back to the work. The hope is that this dalliance with van Gogh will not satiate the hunger of promiscuous pop culture consumers but rather pique their curiosity to pursue a more meaningful and unfiltered meeting with the art itself.

Ft. Lauderdale, Florida

In this bonus video, Lababidi recalls his experience from 2009 in visiting the Francis Bacon Centenary Retrospective at the Met and the poem, “The Museum Going Cannibal” that emerged from that experience, first published in the March 2010 of WLT.