Editor’s Note

when they bombed other people’s houses, we // protested /

but not enough, we opposed them but not // enough.

– Ilya Kaminsky, “We Lived Happily During the War”

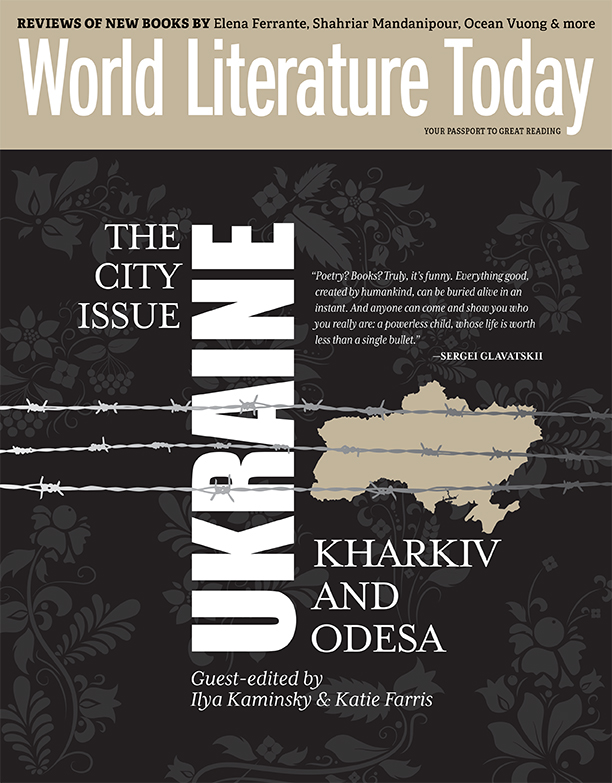

THE LITANY OF Ukrainian cities in the news since February 24 has demanded of the world an urgent geography lesson: Kyiv, Lviv, Kharkiv, Mariupol, Odesa, Irpin, Kherson, Chernihiv, Mykolaiv, to list some of the most prominent names; Bucha, to recall just one place-name forever linked to Russian atrocities. In recent years, World Literature Today has devoted city issues to thriving cultural metropolitan areas like Hong Kong and San Juan, Puerto Rico. With the current issue of WLT, we decided to spotlight two Ukrainian cities: Odesa and Kharkiv. In a gesture of selfless generosity, guest editors Ilya Kaminsky and Katie Farris, along with translators Dennis Kovtun, Yohanca Delgado, Marina Palenyy, NS, Stacey Streshinsky, and Paul S. Ukrainets (as well as Farris and Kaminsky), donated their honoraria to the twenty-two writers gathered in the cover feature. Such gestures help counter the vast devastation—and the litanies of statistics that numb our minds—by humanizing everyday Ukrainians as they confront mass death, calamity, and displacement.

THE LITANY OF Ukrainian cities in the news since February 24 has demanded of the world an urgent geography lesson: Kyiv, Lviv, Kharkiv, Mariupol, Odesa, Irpin, Kherson, Chernihiv, Mykolaiv, to list some of the most prominent names; Bucha, to recall just one place-name forever linked to Russian atrocities. In recent years, World Literature Today has devoted city issues to thriving cultural metropolitan areas like Hong Kong and San Juan, Puerto Rico. With the current issue of WLT, we decided to spotlight two Ukrainian cities: Odesa and Kharkiv. In a gesture of selfless generosity, guest editors Ilya Kaminsky and Katie Farris, along with translators Dennis Kovtun, Yohanca Delgado, Marina Palenyy, NS, Stacey Streshinsky, and Paul S. Ukrainets (as well as Farris and Kaminsky), donated their honoraria to the twenty-two writers gathered in the cover feature. Such gestures help counter the vast devastation—and the litanies of statistics that numb our minds—by humanizing everyday Ukrainians as they confront mass death, calamity, and displacement.

The writers presented here—a range of poets, novelists, playwrights, artists, journalists, editors, photographers, translators, and culture workers—offer firsthand reportage that chronicles the conditions in their respective cities and in nearby countries that have absorbed millions of Ukrainian refugees. They eschew poetry and fiction in favor of eyewitness testimony; Al Panteliat describes his current writing, whether sitting in a bomb shelter or driving through a checkpoint, as “cinematographic”: “Metaphors are a semitone, and in the current reality there is little place for them.”

A persistent theme throughout is the deformations of language during a time of war, especially among the Russian-speaking writers, who confront such euphemisms as “special military operation,” “filtration camps,” and “liberators.” When thermobaric bombs and cluster munitions target hospitals, theaters, schools, and homes, the writer’s first instinct is to document the horror—many compare the current war to Ukraine’s occupation by Nazi Germany during World War II. “Now we have become people,” writes Elena Andreichikova, “that will tell these horror stories to our grandchildren: stories that are impossible to believe.” For Anna Streminskaya, who admits that she could never hold a gun in her hands, “language, the word itself, has become a weapon.” For his part, Evgeny Golubovsky adopts a similar strategy: “The city clings to us: we have to protect it like a child. A writer does this with words.”

Another common refrain since February 24: the writers’ changed sense of time. “It’s almost like time is both hurtling forward and standing still, as if frozen in place,” writes Victoriya Koritnyanskaya. For Anastasia Afanasieva, time stands still in the seconds between the whoosh of a launching bomb and the ensuing explosion: “those seconds were my terror. During those seconds, I prayed.” Just as the city clings to its writers, the authors, in turn, cling to moments of silence as places of refuge, the white blanks between words as spaces of freedom.

Ultimately, writing itself becomes an act of resistance. “It is difficult to speak about the war,” writes Oksana Yefimenko, “because it constantly seems that words are trivial. Every single one of us becomes one of the reverberations of the war’s echo. War takes our voices for itself.” For Ella Leus, listening to the wartime poems of other poets, “their incandescent words are precise like a shot in the temple.” In solidarity with one another, Ukrainian writers are composing a bright new chapter in the literature of witness. As readers, the least we can do is not turn away.

Daniel Simon

The editors would like to acknowledge a generous subvention for this issue from the University of Oklahoma’s European Union Center. We are especially grateful to Mitchell P. Smith, director of the EU Center and associate dean in the David L. Boren College of International Studies, for his support of WLT.

This issue is dedicated to the people of Ukraine.