“Write with New Urgency”: A Conversation with Ben Okri

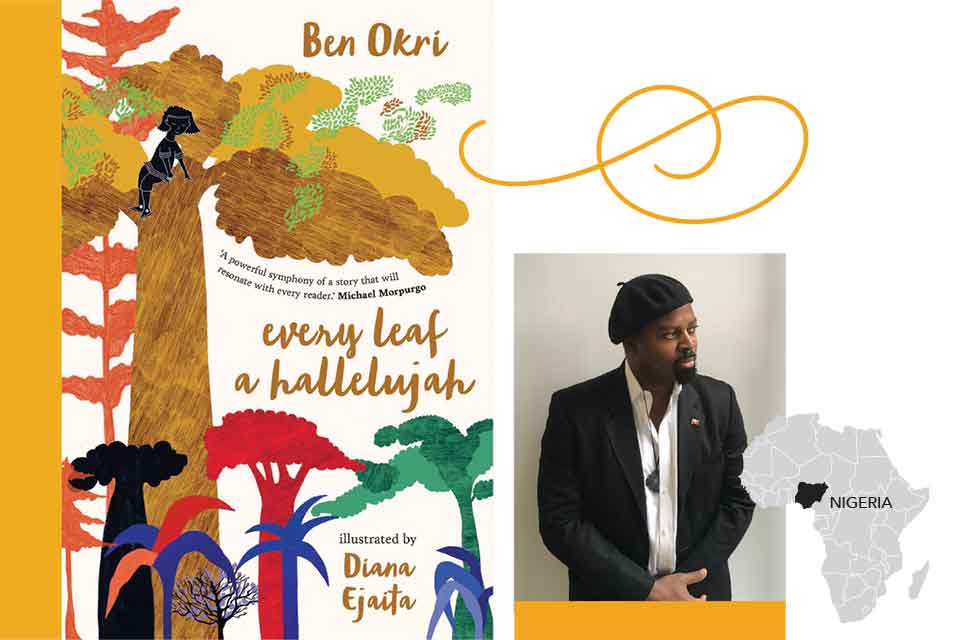

Author of The Famished Road, among other books, Ben Okri has never been a run-of-the-mill writer. He has been hailed as “a literary and social visionary,” and his oeuvre—novels, plays, poetry, haiku, stories—probe essential truths of our times. Creatively, he is as restless as ever, reimagining and expanding his literary landscape. Earlier this year, two new works—an edition of his 1995 quest novel, Astonishing the Gods (featuring a new introduction), and the eco-fable Every Leaf a Hallelujah—were published in the US by Other Press. Here, he speaks about invisibility, consciousness, and the lifesaving powers of literature.

Anderson Tepper: In your introduction to Astonishing the Gods, you explain how the book poured out of you in the summer of 1993. Tell me more about what prompted it.

Ben Okri: The truth is I had been carrying the germ of the idea of the novel since I was a child. I had always wanted to write a story about a person who arrives on a mysterious island. Later I became fascinated by the ancient trope of invisibility. It is there in fairy tales and legends. In Nigeria, in certain traditions, individual disappearance, return, and transformation are linked. Then a strange incident happened to me. It was a racial incident, and it ignited the third link in the magic chain of inspiration. Suddenly I knew who these invisible people of the island were and why they were invisible. The book was written the way it was because of a technique I learned from late Renaissance art, a technique that is also there in the best of traditional African art. And because of the indirect way it’s written, a few people read the novel the wrong way. They thought I was celebrating self-annihilation or some form of social abdication. A few incisive questions would have revealed other layers. Astonishing the Gods had to be written the way it was to be true to its themes. The real question now is, What are its themes?

Tepper: What was it like to revisit the book today, and why publish it in the US now?

Okri: Books are seldom what we think they are. If they are any good, they reveal aspects of themselves not comprehended before. Invisibility is little understood. In a world where everything visible is celebrated, people don’t understand that invisibility is the precondition for true creativity. Writers are mostly invisible when they write. We only see them when the work is done. In the night things grow unseen. In the mind ideas germinate unnoticed. The common aspiration is to be seen.

In a world where everything visible is celebrated, people don’t understand that invisibility is the precondition for true creativity.

But there is another higher invisibility where thought is prepared, where the best work is done, and where true transformation occurs. I think this new paradigm is much needed now in America where there is a kind of arms race of visibility, leading to exhaustion and stress and depletion of the creative and spiritual faculties. I believe there is a reason this book has taken twenty-seven years to come to America. There is a mysterious destiny in books. When a book like this appears in a land, that is when it is most needed. Astonishing the Gods is in America at the right hour. These things happen due to an underlying power greater than individuals. It is perhaps the power of culture itself.

Tepper: Like the book’s hero, you “set out to find one thing, but found another.” What did you discover in the process of writing?

Okri: One of the great things I discovered is that sometimes a book wants to write you, and you should have the humility to let it. But also you must always be ready for when a really deep dream, a big work, needs your aesthetic, your humanity, to come into being. Most books we write, we choose, we determine. But every now and again, for reasons beyond our immediate understanding, a book wants to write you, wants to borrow your hand and your nervous system. Such books reveal their true value over the unfolding years. We think they are one thing, but they turn out to be another. And they go on changing with our changing needs. They are mercurial. They slip through your fingers. They adapt themselves to time.

Tepper: Did this book lead you in a new direction as a writer?

Okri: I’m not sure that books work that way, that they lead on to something else, that they are links in a chain. I think the spirit engages in what it is deficient in, what it needs. Or the spirit operates in what it has too much of, its excessive strength, its repletion. So the work is more cyclical, more contrapuntal, even more call-and-response. The next stage of what Astonishing the Gods opened up as a possibility came much later. And even then I am not so sure. I think Astonishing the Gods is a rare egg. It stands alone in my body of work, a fable about its own secret purpose. And as for new directions, I am taking them all the time. You have to remember that The Famished Road was a radical new direction after the early novels and books of short stories.

Tepper: Every Leaf a Hallelujah is a collaboration with artist Diana Ejaita. Tell me how you worked together and how your daughter, Mirabella, “accompanied” you on the journey.

Okri: The difficult thing was to dream up a story that was environmental in its heart, a fable about courage, animated by a desire to keep alive the love without which no struggle, no campaign, ever truly succeeds. There were two ways to work with Diana. Either she comes up with images that I am inspired by, or I write a story that she illustrates. I had already done the first way with the wonderful paintings of the Scottish artist Rosemary Clunie. We worked on a book together called The Magic Lamp. It’s one of a kind. She made twenty-five paintings over ten years, and I wrote twenty-five accompanying stories over the next five years.

I wanted something different with Diana. So I went off and sought a dream. I went back in spirit to the forests of my childhood. I wandered in parks. Then the story began. Mangoshi, the seven-year-old heroine, came to me. I wrote it over several months. Every day my daughter wanted to know how it was going. When it was finished I sent it to my publishers, and together we chose Diana Ejaita as the illustrator. She loved the story. She was in Ouagadougou at the time. She went to the forests there. Also, she was pregnant with her first child, and she made the illustrations with the sense of this new life growing in her. Hence the wonderful fertility of her drawings. The important thing was that we left her in complete freedom and trusted her artistic instincts. But I did share one small secret with her. When she sent in the illustrations, we gasped with delight.

Tepper: You wrote an essay for the Guardian in which you argue that artists must reckon with the world’s dire climate situation and engage in “existential creativity.” What does this require?

Okri: The demands are purely personal. I offered them to the public only to share where my thoughts and convictions have taken me. If we understand what is happening to the planet, and therefore to us, and if we love this earth and our life on it, then we simply would not be doing most of what we do. There is too much waste. We use up far more energy than we need. We pollute too much. We are overdrawn on the bank of our environmental future. What one does depends on one’s conscience, one’s understanding. But the way we live is no longer sustainable, and each day we contribute to the suicide of our civilization. One does not want to preach, but disaster is staring us in the face. What does it demand of writers? That they use their voice to draw attention to this ongoing catastrophe, and that they write with new urgency. How can one write the same way if one knows that we are drifting toward a terminal condition of the earth?

We are overdrawn on the bank of our environmental future.

Tepper: What sort of work have you been concentrating on lately?

Okri: Last year I had a new play produced at the Young Vic, in London. Called Changing Destiny, it is set in ancient Egypt and was directed by Kwame Kwei-Armah. I’ve had three plays performed in the last three years. Madame Sosostris was staged at the Pulloff Théâtres in Switzerland to full houses. And this year there’s a musical play touring Belgium and the Low Countries called Moby Dick: Queequeg Speaks. Yes, it is the Moby-Dick story, but told from Queequeg’s point of view, and so it’s about race, immigration, abuse of power, identity, and leadership.

In these last few years I brought out quite a wide range of works. The Freedom Artist came out in 2020. A Fire in My Head, my first book of poems in nine years, came out last year. It is a volume that has some of my strongest political poems, including “Grenfell Tower, June, 2017,” a reading of which on the Channel 4 Facebook page has been watched a staggering 6.7 million times. It’s an important volume for me to bring out now. Then there was a volume of stories called Prayer for the Living, which contains some of my best short stories.

Tepper: I was thrilled to hear you speak at the Booker Prize ceremony, thirty years after The Famished Road helped open the way for a new generation of African writers. Are you especially encouraged by the vitality of this work?

Okri: The new generation of African writers are conquering the world on their own terms. One can now quietly say that African literature is among the most powerful in the world. And The Famished Road helped that explosion. Winning the Booker was vital to this, but I think the real surprise is that the novel continues to live, continues to grow. It has been called magical realism, animist realism, fantasy, spiritual realism, African realism, and so on. It is none of those things, or it may be all of them, plus some other – isms too. It has just been reissued as an Everyman Classic, the first African novel since Things Fall Apart to achieve this status.

The thing about all my books is that you ought to come to them with a fresh mind. I don’t do what has been done before. I do new things and I find new ways. Literature ought to wake us up to the miracle of life and being and the possibilities of mind and consciousness. Literature ought to help make us agents of change, ought to wake us up to our essential freedom, the freedom to make this world as we want it. We can’t do this if we see the world in the same way that led to the world being as it is, hurtling toward environmental crisis and the shrinking of freedoms and the slow loss of selfhood. We need a new consciousness to make a new future. Literature ought to be that new consciousness.

February 2022