On War and Borders, Italian and Beyond

Borders have always been a big bone of contention for Italy as a geopolitical entity. For centuries, its territory was fragmented, subdivided into city-states, duchies, seigneuries, run by local and foreign rulers. Even after it was unified in the late nineteenth century, the boot remained frayed around the edges, with the northeastern regions becoming the stage of bloody battles throughout the world wars, as the so-called unredeemed lands considered “naturally” Italian were reclaimed by patriots.

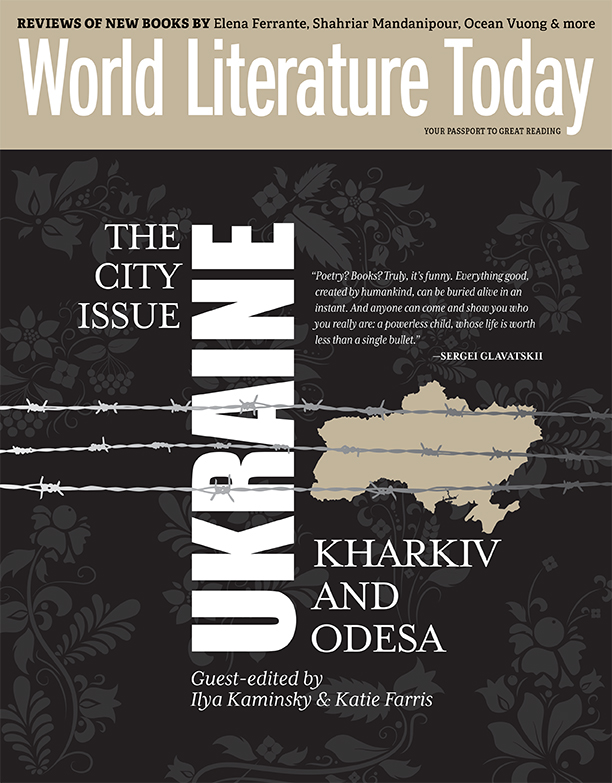

It strikes me that this idea of a war justified by a territorial right grounded on a “natural” state of things needing to be restored is still haunting Europe, as we are confronted with spine-chilling images of ravaged cities, gutted buildings, refugee trains fleeing the ruins of Mariupol, Kyiv, or Kharkiv. Human lives are sacrificed in the name of a political and cultural identity that aspires to singularity rather than plurality, sameness rather than diversity.

Because of its past, Italian literature is a privileged space to understand the present moment through its war literature produced in the first half of the last century. On the other hand, as Rosie Goldsmith mentioned recently in the Italian Riveter, echoing an interview with Jhumpa Lahiri, Italian literature is enjoying “a moment.” This is perhaps due to the fact that its borders with otherness are becoming less neatly defined, more porous, welcoming to diversity. Italy no longer fears losing control of its boundaries.

Here are some suggestions of Italian books dealing with war and borders.

Giuseppe Ungaretti

Giuseppe Ungaretti

Allegria

Trans. Geoffrey Brock

Archipelago Books

BORN IN EGYPT to Tuscan migrants in 1888, 1970 Neustadt Prize laureate Giuseppe Ungaretti is one of the most popular twentieth-century poets in Italy, with his first full-length book of verse now available in parallel text, the original Italian and its award-winning English translation. The poems were written in the muddy trenches of World War I, when the poet was drafted to fight in the Karst upon his return to Italy. Despite feeling the strong call of his “fatherland”—nurturing the affirmative tone of poems such as “Vigil,” in which the poet describes being “flung beside / a butchered comrade” all night long and yet writing “letters full of love”—Ungaretti identifies as a nomad, shattering linguistic and cultural borders.

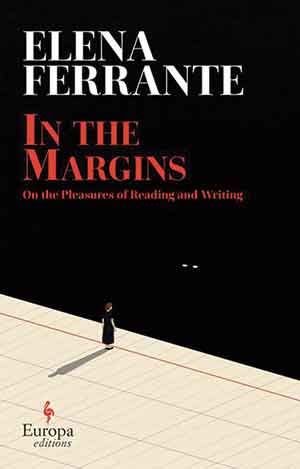

Elena Ferrante

Elena Ferrante

In the Margins: On the Pleasures of Reading and Writing

Trans. Ann Goldstein

Europa Editions

IN HER LATEST collection of essays, the world-acclaimed author talks about two impulses animating her writing, one “compliant” and the other “impetuous.” The first abides by the rules dictated by authority—of teachers, editors, publishers, audiences—that requires you to stay within the set margins of what constitutes correct and beautiful expression; the other is vehement and unruly. In four compelling essays brimming with citations from her literary models, Ferrante outlines an itinerary of personal discovery that brought her to rupture the patriarchal cage in which she was confined and listen to female voices in Italian and global literature, embracing them in her writing.

Claudia Durastanti

Claudia Durastanti

Strangers I Know

Trans. Elizabeth Harris

Fitzcarraldo Editions

ACCEPTANCE of the other plays a crucial role in Claudia Durastanti’s novel, a coming-of-age story in which the protagonist, the daughter of deaf parents, maps out the places where her nomadic identity develops amidst a constant sense of fluctuation, nonbelonging, in-betweenness. If it is true that “art can free an individual from difference, and difference from solitude,” with her nonlinear memoir Durastanti’s narrator invents a new hybrid artistic form to bridge the gap between her deaf parents—who believe only in literal truths—and her constantly shifting self. The notion of deafness as disability is deconstructed and challenged as the narrator suggests synesthesia, or a poetic blending of the senses, to define her mother’s condition.

Marta Barone

Marta Barone

Sunken City

Trans. Julia MacGibbon

Serpent’s Tail

AT TIMES, WHAT urges to be told not only has no clear outline but is better defined as an absence. This is the case in a few contemporary novels written by women striving to portray the father figure, but in Sunken City the struggle of the first-person narrator chasing her own father, L.B., becomes a quest for a bigger truth. Allegedly associated with armed groups of the extraparliamentary left in the 1970s, and charged with participation in hideous crimes, L.B. emerges from the written page like the mythical sunken city of Kitezh, “of which lucky wayfarers occasionally still glimpse its white-and-gold outlines beneath the surface of the lake.” Through that liquid mirror, both the collective history of Italian terrorism and the personal story of L.B. remain caught in a liminal space in which the boundaries between truth and lie, history and fiction, memory and dream are bound to remain forever blurred.

When you buy a book using our Bookshop Affiliate links on this page, WLT receives a commission. Thank you for your support!

Read Ferrara’s full review of In the Margins from this same issue.