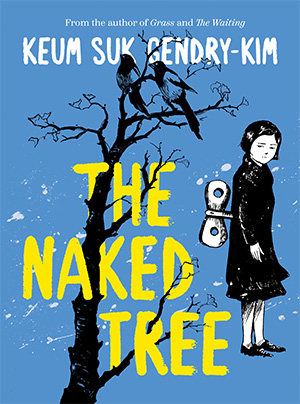

The Naked Tree by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2023. 312 pages.

Montreal. Drawn & Quarterly. 2023. 312 pages.

Readers familiar with Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s work may find The Naked Tree a departure from the frontline documentary realism of The Waiting (2021) and Grass (2019), where the most ravaging and enduring consequences of war (forced migration, sexual enslavement, separation, and—equally painful—reunion) are depicted with a biting mix of journalistic objectivity and narrative empathy. Unlike the two previous titles, which rely on testimonies and interviews, The Naked Tree is an adaptation of Pak Wan-sŏ’s (1931–2011) autobiographical first novel (1970; Eng. 1995). As such, it develops a more subdued and meditative approach to a set of ongoing thematic concerns, while stylistically enriching the poetic expressionism of the brushwork with a delicate use of the graphic line, especially in the close-up portraits of the two protagonists.

Set in Seoul during the Korean War, the book explores the romantic relationship between the author (renamed Lee Kyeonga) and the painter Park Su-geun (1914–1965), when they were both employed by the American PX (Post Exchange), a duty-free retailer serving American troops. Here, Miss Lee’s main duty is to flirt with GIs and convince them to have the photographs of their girlfriends or wives painted on silk scarves and mailed back home. Flirtation is tricky and may result in racial or sexual harassment, or both, if not a reciprocally exploitative interracial relationship. Although frequently subjected to the former, Miss Lee draws a line when it comes to the latter. But she is both romantic and lonely, and when her department hires a third painter, she is naturally attracted to the elusive and very talented Ok Huido (Park’s fictional name), who never had a real job and claims to be “just a painter.” He is also a husband and a father of three, and this, we believe, is what prevents him from pursuing his vocation—but also his relationship with Kyeonga—freely and fully.

Art and love are thus equated as simultaneously subject to historical circumstances (the emphasis is on war, but social conventions and traditional values play a constraining role as well) and situated outside their reach, in a never-never land unblemished by conflict, suffering, or desire. Confronted by the prospect of a love affair, the two swerve to avoid the abyss they are facing. Kyeonga claims that she longs “to begin a new life through Ok Huido” (not with but through him), a rather ambiguous statement, especially in view of what follows: a cathartic night spent in a hotel room with a GI and eventually a comfortable, uneventful, bourgeois marriage with an electrician from the same town as Ok.

Having begun with the married couple reading Park Su-geun’s obituary, the book ends with a major exhibition of his work, four years later. There Kyeonga recognizes a painting of a naked tree she has seen on her last visit to Ok’s studio. But in the meantime, the fame of the deceased artist (who lived in poverty for most of his life) has skyrocketed, making his work unaffordable to most. “It’s all because of the war,” her husband comments. “It seems like yesterday, but no one remembers anymore.” Yet remembrance will help his wife become an artist in her own right and continues to inspire and shape Gendry-Kim’s superb graphic and narrative talent.

Graziano Krätli

North Haven, Connecticut