Japanese Fairy Tales for the Modern Moment

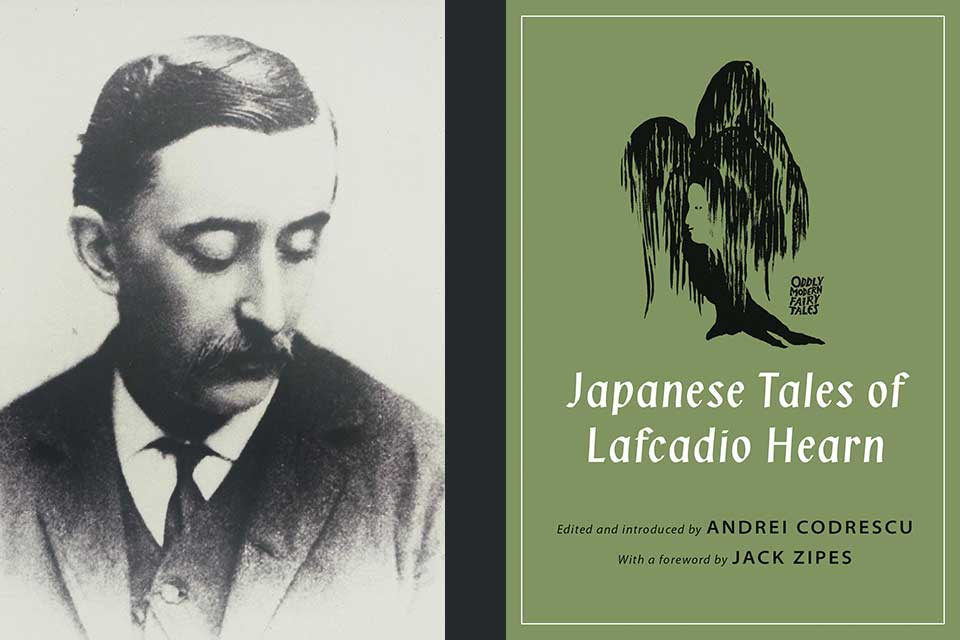

Born in Greece in the mid-nineteenth century, Lafcadio Hearn shuffled between Ireland, the West Indies, and a few cities in America before landing in Japan, where he would finally settle down and spend the rest of his life. It was there that he would begin the work that he became best known for. Hearn became a collector of sorts of Japanese fairy tales and folk stories, and his retellings of them captivated audiences in both the West and in Japan, leaving an impact on both literary traditions.

Japanese Tales of Lafcadio Hearn, edited by Andrei Codrescu (Princeton University Press, 2019), contains twenty-eight of these stories that are based in Hearn’s own studies of Japanese folktales but are influenced by a lifetime of navigating different cultures. The result is a uniquely transcultural kind of storytelling—something that feels familiar to Western audiences despite being wrapped in entirely different histories and cultural codes. Within Hearn’s stories are subtle traces of Hans Christian Andersen, Greek myth, and Creole storytelling among the distinctly Japanese tales.

Within Hearn’s stories are subtle traces of Hans Christian Andersen, Greek myth, and Creole storytelling among the distinctly Japanese tales.

While Hearn wrote in many genres, this collection focuses on one of Hearn’s biggest preoccupations: fairy tales, ghost stories, and myths. Each of them brings the strange and implausible uncomfortably close. They take place in a world where the lines of reality are not so sharply drawn. The border between life and death is a permeable one, allowing for the afterlife—a place every bit in motion as life—to spill over. In one of several such stories, “The Story of Mimi-Nashi Hoichi,” a blind biwa player spends his evenings unwittingly playing for a crowd of ghostly soldiers.

The distinction between life and death is not the only one that becomes blurred, but also between human and nonhuman, reality and dream. Demons and spirits walk among humans, taking different forms, but so do humans become demons or spirits, their negative emotions transfiguring them into something twisted. Even artwork comes to life with the essence of the subject, such as in “The Screen Maiden” or “The Story of Kōgi,” and then leaves the canvas to enter the realm of the living.

At any point, the foundation for one’s entire life can be revealed to be an illusion, crafted by some inscrutable force and then shattered in a moment.

This gives the stories an atmosphere of uncertainty; nothing is a given in the world of these fairy tales. At any point, the foundation for one’s entire life can be revealed to be an illusion, crafted by some inscrutable force and then shattered in a moment.

One of the strongest points of this collection is the accessibility that it offers to readers unfamiliar with Hearn’s work. The introduction and foreword provide a clear context for the stories that follow, which are all filled with the original footnotes. Readers don’t need to be overly familiar with Hearn himself or the broader tradition of Japanese storytelling in order to be able to enjoy the book. Given the profusion of Hearn’s work, it can be difficult to know where to start, but the selection of works in the book are a strong sampling, which will give readers a good place to dive in.

While the stories in the book are over a hundred years old, they have a lot to offer to twenty-first-century readers. The look into traditional Japanese culture is valuable on its own, but Hearn’s unique transnational re-renderings of the stories give an insight into a kind of cultural production that is fitting for a time period with an unprecedented flow of knowledge and culture across borders. There’s also something to be said about the stories’ ability to place readers back into a time period filled with a different kind of uncertainty than we currently face. In Hearn’s fairy tales, there is still room for the nebulous and unknown, and within it, still much to be in awe of and, at times, to fear.

Oirase, Japan