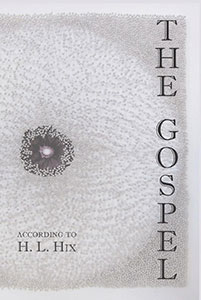

The Radical Gospel of H. L. Hix

The Gospel According to H. L. Hix (Broadstone Books, 2020) is an audacious book that foregrounds translation as a means of critiquing our understanding of the stories about Jesus that have animated Western culture for two millennia. Discarding the binary of canonical and noncanonical texts, H. L. Hix braids the extant strands of various texts to weave a found narrative tapestry that is both distinctive among gospels and linguistically arresting.

The Gospel According to H. L. Hix (Broadstone Books, 2020) is an audacious book that foregrounds translation as a means of critiquing our understanding of the stories about Jesus that have animated Western culture for two millennia. Discarding the binary of canonical and noncanonical texts, H. L. Hix braids the extant strands of various texts to weave a found narrative tapestry that is both distinctive among gospels and linguistically arresting.

Hix lays out several conceits in his introduction to the book that shape the contents within in an otherworldly form. All of the text within is taken from historical documents associated with early Christianity, so there are no fictionalized narratives or psychologizing of the characters that didn’t originate in a gospel. Though many of the stories taken from those gospels will be familiar to those with even a cursory familiarity with Christianity, the language used to tell them will not. Words that have accrued too much baggage due to their association with various authoritative translations in the past are ditched in favor of mundane substitutions. Thus, “The Lord” becomes “the boss,” “Spirit” (as in the Holy) becomes “breath,” “Heaven” becomes “the sky,” and even “messiah” resolves into “the salve.”

Though many of the stories taken from those gospels will be familiar to those with even a cursory familiarity with Christianity, the language used to tell them will not.

Taken broadly, this is an effective tool as it removes the cognitive guardrails put into place by two thousand years of cultural literacy and places the reader on a more even playing field with the text. It does sometimes result in the downcycling of much-beloved turns of phrase into formulations less grand in their euphony, as in this passage from the gospel according to Matthew that reads (in the King James translation): ”Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven,” which Hix renders as “Graceful, the poor in breath: theirs is the realm of the sky.” Others maintain the register of their more-famous cousins and take power from the simplicity of their delivery, as in Jesus’ famous exhortation (also from the book of Matthew), “In everything act toward others as you would have them act toward you.”

While these narrative devices might be adequate to turn away biblical translation purists, Hix’s choice to degender divine personages within the story swiftly carts his gospel from the realm of, “Oh, let’s make this accessible” to “Oh, this is about to get really weird.” Rather than describe the algorithms employed to pull this off, better to get a sample of it direct from the source.

So much did the god love the world, that xe gave xer only xon so that all who believe in xer will not fall into ruin but have timeless life. The god did not send the xon into the world to judge the world but so that through xer the world would be preserved.

Hix defends this decision in his introduction, noting that his translation seeks to “overcome a feature that the original languages and English share,” justifying this aim with a call for a “gospel universalism” that is applicable not only to ethnicity or nationality but also to gender. While the theological implications of that are no doubt best debated among scholars (and readers) with cosmological skin in the game, it does add an element of surreality to a once-familiar text that I found satisfying. When combined with the various “weird on their own merits” narrative strands rescued from apostasy by Hix’s ecumenical editorial eye, the word choice allows his gospel to reinhabit an otherworldly register that must have surely accompanied these texts as they originally made their way in the world. Hix’s Jesus exhorts the Pharisees to “Hear me delicately, understand me roughly. I am xe who laments, face down in the dirt. I prepare my own bread and my own mind. I know the known that the name names. I am xe who cries out and xe who hears the cry.”

Hix’s word choices allow his gospel to reinhabit an otherworldly register that must have surely accompanied these texts as they originally made their way in the world.

When biblical scholars (which I am not) approach the source texts from which The Gospel According to H. L. Hix is derived, they come bearing a tool belt of critical strategies that allow for the purposeful dissection and classification of the contents. This text is resistant to many of those strategies because it is a composite of materials that were considered to be too divergent to be contained within one coherent theology. Structurally, it is a fairly consistent mix of stories about Jesus, including robust sections on Mary’s and Jesus’s childhoods that aren’t part of the standard model, and things Jesus said. The teaching stories brought in from the Gnostic tradition resurrect a mystic tradition all but banished from the faith, carrying echoes of Eastern traditions and Pythagorean ideas that were washing about in the spiritual tide pools of the Roman Empire. More than a few of the added parables are oblique enough that the reader can’t help but sympathize with the baffled disciples who don’t know what Jesus is exactly getting at.

The sum of all this narrative play is a wonderfully complex, occasionally self-contradictory, occasionally self-referencing translation that is, to some extent, about translation, the mechanism by which all of these texts have endured into the modern era and context. Whether it coheres into a unified body of scripture capable of supporting the scaffolding of religion that has been welded to the exterior of these gospels or not, Hix’s pointillistic sketch of the life and times of Jesus the salve is an engaging read.

University of Oklahoma

Editorial note: Hix’s “Belief in an Age of Intolerance” essay appeared in the November 2017 issue of WLT.