Marie Ross’s Brahms

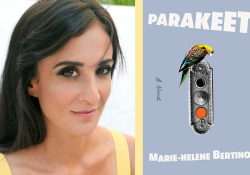

In this profile of clarinetist Maire Ross, Olga Zilberbourg explores how Ross, with her 2019 CD Brahms: Clarinet Sonatas and Trio, asserts her agency as an interpretive artist against the musical tradition.

As a sixteen-year-old clarinet student at the competitive Interlochen Arts Camp in Michigan, Marie Ross encountered a difficult passage in a Brahms piece she was learning. The second, slow movement of his first clarinet sonata includes a moment of rising action, a crescendo, followed by a sudden softening.

Ross’s teacher was frustrated with her execution of this transition, which he ascribed to her being too young to understand this music. Looking for ways to encourage the budding musician to make the passage more dramatic, he told her to imagine “angels who are coming to tell you all the secrets of the universe—and then, right at the last moment, they turn away, and decide not to tell you.” She liked the image, but his musical direction felt wrong to her.

She explains that many music teachers use images that might sound “cheesy” to adults to help young students access larger emotions and to think about the music as more than just notes on a page. That image became meaningful for her, and yet, to this day, she disagrees with her teacher. “I think I had a pretty good grasp on this music when I was a teenager,” she says. Ross continues to believe in her youthful vision. Twenty years later, Ross, a member of the acclaimed French Ensemble Matheus and a professor at the University of Auckland, laughs at the memory. She and I are talking on Skype, and before the video cuts out, I glimpse that her closely cropped hair is blond-colored. On the CD cover, it’s magenta.

From the beginning of her career, she resisted playing music like everyone else. She had her own ideas.

In 2018, working on her groundbreaking recording of Brahms’s Sonatas and Trio for Centaur Records label—revered pieces of the chamber music repertoire that she had first learned to play at Interlochen—Ross held her teacher’s image of angels in her mind as she approached that passage. She’d added to that image a great deal of knowledge about Brahms and the circumstances under which he wrote and performed these pieces. Learning the history of her instrument, she understood that Brahms-era late Romantic clarinets had more in common with Mozart-era predecessors than with the modern machine-built clarinets on which Ross first learned to play.

Brahms-era late Romantic clarinets had more in common with Mozart-era predecessors than with the modern machine-built clarinets on which Ross first learned to play.

There’s a line that music students and professionals often hear, Ross says: “We have to respect the composer’s intentions.” What this usually means in our era of recorded music, she says, is playing to an established consensus of how a particular piece has been performed by other musicians. Even to a professional listener, a piece of classical music recorded by different ensembles trained on modern instruments often sounds very similar, a matter of small variations of technique and recording quality. This dominance of canonic interpretations effectively handicaps the performers, robbing them of the ability to approach the music with their own ideas and understanding.

But Ross, with her 2019 CD, has achieved another goal: she has asserted her agency as an interpretive artist against the musical tradition. The CD is noticeably different from the recordings of the same material completed on modern instruments, and even from the one earlier recording made with historical instruments. It’s noticeably longer—by approximately twelve minutes, an astonishing variation—and the sound of each instrument has distinct textures that even a nonprofessional listener will easily pick up on. To me, it felt less like a performance directed at the public than a deep conversation between friends, in music.

Ross’s CD felt less like a performance directed at the public than a deep conversation between friends, in music.

And it has been well received by the music community. “What I hear in all three works is playing of grace and piquancy, informed, we may be assured, by the lessons imparted by having one’s fingers connected to instruments of the time,” writes Benjamin Dunham for Early Music America, a professional organization for musicians working in the field of historically informed performance. “The change in mood with that oh-so-lyrical opening to [Sonata no. 2] packs in so much in just the first minute that we’re kept on the edge of our seats wondering what will happen next, and this of course is the point of such a recording; giving us that freshly minted feel of music that is new and full of surprises,” writes Dominy Clements for MusicWeb International, the largest noncommercial classical music resource on the internet.

Ross’s journey to this recording started at a young age, when she looked for ways to deepen her relationship to the music that everyone was studying for auditions. Then, one day in 2006, when she was a second-year master’s student at the San Francisco Conservatory, she needed to get her clarinet fixed. Her teacher, a member of the San Francisco Symphony, recommended a master, Daniel Deitch. She called Deitch, and he invited her to his workshop, which was on the other end of the city. It took Ross over an hour and three buses to get there. Once she arrived, she was relieved when the master invited her to stay while he worked on her instrument. The job would take three hours, he said. She was welcome to look around.

On the wall, Deitch had hung up woodwinds from different periods, some of them rare: a metal clarinet, an odd-looking bass clarinet. Deitch explained that he also built and restored historical clarinets. Among them was a five-key Classical-period clarinet that he removed from the wall, offering Ross to try it. Years later she recalls “this sweetness and intimacy to the sound that I’d never heard before and had never been able to make before. I think that the physical feeling was as much what I fell in love with as the sound of it. There was something about just having my fingers directly on the wood instead of touching the metal keys. It felt quite different, more connected to the instrument.”

She was inspired and wanted to know more about how to play this instrument. Prior to her time at the San Francisco Conservatory, Ross had studied at the Eastman School of Music, and after San Francisco, she went on to a PhD program in modern music performance at the University of North Texas, and even as she went on perfecting her technique, she looked into opportunities to learn more than what these programs were giving her. She had to make her own path—and she did, by applying to the Royal Conservatory in the Hague, which at the time was one of the few full-time programs in the world that specialized in historical performance.

At the Hague, Ross had to start her training from scratch, relearning how to play a basic scale on an instrument from the 1700s. She studied instrument-making and learned how to make a clarinet from a piece of boxwood. (The modern instruments, she says, are made from blackwood instead, sourced in Africa—it’s a denser wood, better suited to machine production methods.) A clarinet is a relatively new instrument that went through several radical changes in its design. If clarinets of the Classical period for which Mozart composed are relatively simple pieces of wood with a few holes and metal keys, contemporary instruments designed to produce consistent sound are complex contraptions of wood, keys of metal alloy, mouthpieces of hard rubber, cardboard and felt or leather for key pads, metal springs, cork and wax for joints, and so on. In the second half of the nineteenth century, most musicians in France, Belgium, Italy, and the United States adopted the so-called “Boehm system” of keywork, while clarinetists in Austria and Germany turned to the “Oehler” system. This division persisted into the twenty-first century, meaning that any US clarinetist who wants to play in a German orchestra must learn new finger placements.

In the space of a few years, Ross packed in historical and practical knowledge about several hundred years of music history. She first attempted to perform Brahms at the Hague, but her teacher didn’t like the idea. As a clarinetist specializing in historically informed performance, Ross would spend most of her career playing music from the Classical period, he argued. He wanted her to focus on that, instead of taking on a composer associated with the much later Romantic period. Why take the time to learn an instrument you would never use?

A clarinet is a relatively new instrument that went through several radical changes in its design.

Until recently, Ross says, musicians studying historic performance overlooked the late Romantic period. Brahms died in 1897, removed from our time by only a few generations of players, and many believe that contemporary performing practices and instruments have only improved the performance quality that he had envisioned. Ross and a colleague, Soren Green, who was also interested in playing Brahms, wanted to test this theory. They started assembling their own collection of instruments, buying old pieces on eBay. “We got them for no money at all, maybe sixteen euros, and they were green with mold,” Ross says. “We sat around in his flat in the Hague and took all the keys off, cleaned them, and repadded.” (Green later left performing and became an instrument-maker.)

Brahms wrote his four clarinet pieces for chamber ensembles late in his career, in 1891 and 1894, having already declared his intention to retire from composing. He was inspired to write these works after hearing Richard Mühlfeld, a clarinetist whose sound he found particularly warm and expressive. To approach Mühlfeld’s sound, Ross found clarinets made by a legendary German maker, Oskar Oehler. She uses two instruments, one that was made in the 1890s, and the other in 1905. The latter instrument has ties to a musician in the same orchestra in which Mühlfeld also had played. Mühlfeld, Ross says in the liner notes to her CD, is on the record for recommending Oehler clarinets.

Brahms died in 1897, removed from our time by only a few generations of players, and many believe that contemporary performing practices and instruments have only improved the performance quality that he had envisioned.

Learning to play the Oehler instruments was another matter. The Brahms pieces that are fairly straightforward to play on the modern instruments become difficult to execute on the historical instruments, with sound quality harder to control. Mühlfeld was able to achieve his expressivity with his clarinets because he had been playing them in the course of his career (after his initial training as a violinist); Ross was under pressure to move a lot faster. These days, it’s uncommon for musicians to take a year or more to create a single recording, she says. “I know musicians who make three recordings in a year.” In the contemporary YouTube-dominated climate, even established orchestra musicians are starting to worry about job security and are feeling a lot of pressure to take on extra gigs.

Ross gave her first public performance of Brahms on the Oehler clarinet during the defense of her doctorate at the University of North Texas in 2014. She recalls being nervous as her project became a massive undertaking. Successful defense did not satisfy her own desire for perfection. She performed Brahms as much as she could during the next few years in Europe and the United States. In 2016 she moved to New Zealand and began teaching at the University of Auckland. There, she spent a solid year preparing just for this recording, practicing the pieces daily, averaging about three hours each day.

During this period, it became painfully clear that one of Ross’s clarinets—the 1905 piece that had been played more—had a serious problem with intonation. It basically sounded off-key. This problem, too, had a historical reason. In Brahms’s era, intonation wasn’t a priority for the instrument makers. Valuing the dark, rich tone of the instrument, they made the conscious decision that certain notes would be out of tune. “Now, fast-forward to 2019, and it’s really not acceptable to make recordings that are out of tune, even in the name of historical performance,” Ross laughs.

To work on this problem, Ross flew from New Zealand to Europe. After an Oehler specialist in Germany was unable to fix it, she sought out a clarinet maker in Belgium who refreshed the instrument in a way that would’ve been closer to the way it had been when it was originally made, before its decades of service. At the end, Ross still had intonation issues with it, and when she played it, she had to change her fingerings and make temporary adjustments to the instrument itself, for instance, placing wax inside the holes to make them smaller and putting little pieces of cork underneath a key.

It was the summer of 2018 before Ross returned to Europe to rehearse with the other musicians who would appear on the recording, Petra Somlai, the pianist, and Claire-Lise Démettre, the cellist. After the recording was complete, it took many more months of work with the engineer Dirk Fischer to perfect the sound quality. The recording was finally released on November 15, 2019.

Ross is deeply proud of the way the CD ultimately turned out. “I always have this idea in my head of what I want a piece to sound like,” she says, and it can be very frustrating when she is unable to achieve that sound. Most of this recording does match up with what she’d imagined. For any artist, successfully conveying what you want to say is most difficult.

For her next recording, Ross plans to tackle the Clarinet Quintet that Brahms wrote during the same period for Richard Mühlfeld. It’s a much longer piece of music and requires a group of string players to accompany the clarinet. She’s also getting ready to teach a class, “Exploring Historical Performance,” to second-year undergraduate students. As she helps make information about historical performance available to students who are much younger than she was when she discovered it, Ross hopes that this knowledge will help them develop their own individual performing styles and feel freer to rebel against the canon.

San Francisco