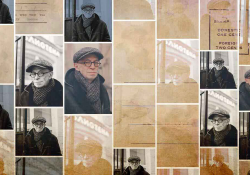

A Conversation with Vladimir Lorchenkov

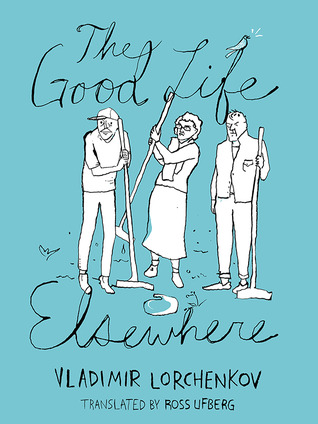

New Vessel Press recently released The Good Life Elsewhere, Vladimir Lorchenkov’s scathing satire from Moldova. Born and currently living in Moldova, Lorchenkov is a laureate of Russia’s 2003 Debut Prize and the 2008 Russian Prize. For ten years, he was the crime section editor of a Moldovan newspaper.

New Vessel Press recently released The Good Life Elsewhere, Vladimir Lorchenkov’s scathing satire from Moldova. Born and currently living in Moldova, Lorchenkov is a laureate of Russia’s 2003 Debut Prize and the 2008 Russian Prize. For ten years, he was the crime section editor of a Moldovan newspaper.

The Good Life Elsewhere follows the tragicomic efforts of the citizens of a Moldovan village to immigrate to Italy—their version of heaven—against the backdrop of Moldova’s ever-developing relationship with the EU, Russia’s still-dominating shadow, and Italy’s xenophobia.

Michelle Johnson: In The Good Life Elsewhere, Moldovan villagers engage in a variety of over-the-top attempts to immigrate to Italy, and these efforts seem to grow more outrageous as the novel proceeds. Why did you choose tragic comedy, even the grotesque, to tell this story?

Vladimir Lorchenkov: Text isn’t my master; I am the master of the text. First, tragicomedy is my deep perception of the world. Homer did not write fiction. He described the world only known to him: his way of expression. I do the same. For me, flying tractors, the gods of water, medieval chronicles, and drying garlic on hanged women—like Olympian gods for Homer—aren’t just figures of speech or images. They’re part of my existence and mode of seeing the world.

I’m not saying anything new when I say that the number of stories is limited in world literature. Journey and return home (Odyssey), love (Romeo and Juliet), betrayal (King Lear) . . . The most that we modern writers can do is combine several plots in one story. In The Good Life Elsewhere, I told the story of people’s eternal pursuit for heaven, the desire to get “elsewhere good” and the eternal return home. Unlike Odysseus, my heroes try to leave their Ithaca/Larga using all known and unknown methods but without any result. Fate—or the will of the gods, if you prefer—constantly prevents them from leaving Larga. In this sense, my novel is no different from Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath and other stories of perpetual motion, except that Steinbeck, unlike me, didn’t edit the crime section of a newspaper, so he didn’t shake off minor characters with such ingenuity. But, as I have heard, Steinbeck really liked whiskey. So I am happy to have something in common with this great writer.

By the way, I wouldn’t say this is a story about Moldovans and Italy. With the same success it could be a story about Mexicans and the US or conquistadors and Latin America. It is about the pursuit of a dream, a crusade for paradise. That’s why I stylized the book in part after the medieval chronicles. My heroes are obsessed with reaching the Promised Land of milk and honey. And if we are talking about such things, we need fantastic exaggerations. When you talk about the monstrous absurdity of life, you need only the grotesque.

MJ: Who are your tragicomic inspirations?

VL: I can’t say that my specific sense of humor and perception of the world were formed by literature. Perhaps I was born with this worldview, and it, along with my life, have made me like this.

In general, though, the writers who inspired me to start writing books are primarily great Americans: Faulkner, O’Connor, Steinbeck, Fitzgerald, Saroyan, Mailer, Miller, Updike, Bukowski, Heller, Malamud, McInerney, Capote, Kerouac, Doctorow, McCarthy, Salinger. I speak about them not because I’m giving an interview for a US magazine. I am deeply convinced that in the nineteenth century, the center of world literature was in Russia, and it then moved to North America in the twentieth century. Moreover, given my plans to immigrate to Quebec this year, I will try to maintain this status quo (smile).

And then there’s the influence of the environment: Moldova itself is absurd enough—although I would not exaggerate this absurdity—and provides a lot of material to the writer. Here is an example: I began in 2003 to write The Good Life Elsewhere and figured out how the villagers form a curling team—surely a crazy idea for Moldovans—to travel to competitions in Norway and to immigrate. I thought it was amazingly absurd, even grotesque. Later I learned that the same year, some women created a false Moldavian team of underwater hockey—an even crazier idea than curling for Moldova—to go to the World Cup in this sport and emigrate en masse.

MJ: I read your humor, at least in translation, as very tongue-in-cheek with a strong use of simile rather than metaphor. Metaphors are notoriously difficult to translate, unless they’re body metaphors, which tend to be more universal. Did you take this into consideration when you were writing the novel? In other words, do you write with an eye to future translations?

VL: I could not imagine that this book would be published in Russia in the original language (Russian). I have never considered myself a real writer, like the ones shown in the movies. (However, I always like the image of the writer’s life shown in the television series Californication with David Duchovny.) Therefore, I did not have in mind writing for translation. I just wrote for fun; I was telling a story.

Why the simile, not a metaphor? I just love the theater, and when I write I like to imagine a picture of the events. I prefer to think in images rather than words. I suppose that the writer should “show instead of tell.” I am deeply convinced that the literature of images is the sole future of literature. As for the translation, I am honestly still amazed that my book has been translated. Yes, I’m a good writer, but the history of literature teaches us that this is not enough to become popular and receive recognition.

MJ: The novel begins in 1993 and moves through 2005. To what extent does it reflect the current political climate in Moldova and the view of Moldovans toward immigration to Italy?

VL: Believe me, nothing has changed since 1988, when the anarchy began here. In Moldova, everyone wants only one thing—to leave—and not only to Italy, which I chose accidentally. Huge numbers of people emigrate to Russia, Canada, Portugal. . . . They don’t care where: elsewhere from Moldavia is enough for Moldovans. Emigration is a kind of “American dream” for Moldovans—the main idea, the imperative of life. If Moldovans spent all their efforts to leave Moldova on creating a normal state instead, they would be living in paradise. Actually, this is one of the topics of my book. People are chasing a dream, not realizing that Moldova’s performance is in their heads and hands. But to understand this simple idea, people need journeys. It’s like going on a crusade, miraculously surviving under the walls of Jerusalem, in the deserts, on the stormy sea . . . to eventually return to one’s native village in France and understand that heaven is here, in your own house. And only you yourself can make your home paradise. Or hell. Alas, Moldovans are more successful at the latter.

MJ: The hysterical chapter in which the folklorists visit Larga includes this campfire-side comment: “It seems that contemporary Italy takes the place of a general afterlife in the consciousness of the peasants.” Though you may be using exaggeration, what is the grain of truth here? And why Italy?

VL: What exaggeration? This is true as it is. The locals are obsessed with Europe as well as everything European—the Promised Land of the Middle Ages. It is faith, something irrational. They don’t want to do anything, don’t want to change their lives by European standards. They are just sincerely convinced that Europe will give them a lot of money. It’s like Santa Claus and children, although the comparison with religion is more precise. In the continuation of The Good Life Elsewhere—in the novel called Tabor Leaves—I wrote that religion arrived in Moldova as “Euro-cargo.” This is analogous to a cargo cult. Its adherents sincerely believe that EU flags hanging everywhere can cure illnesses, bring rain to the fields, and improve the economy. Certainly, later I will be asked if there is a grain of truth in the grotesque. But it is reality, not the grotesque. Come to Moldova and see. For Moldovans, it is easier to disguise a crack in the wall by the flag of the European Union than it is to fix this crack.

MJ: You are moving to Montreal. Is Canada your Italy?

VL: I am not only the character of this book—although I am a kind of character—but also its author, its creator. So I understand a lot more than my heroes. My heaven, my “Italy,” is myself. But besides the fact that I am the creator, I am a human too, which is why I have to perform some social functions. For example, I am the father of two wonderful children. I do not want to see them growing up in a country where tuberculosis is as familiar a disease as the sniffles, and where a pack of stray dogs can tear a person apart on the main street. But my attitude toward immigration is not quite the same as that of Moldovans generally. I understand—although for many of my compatriots it sounds incredible—that I’ll have to work hard in Canada and that milk and honey do not flow through the streets anywhere, even in very rich countries.

MJ: Let’s address the more scathing side of the novel. Though quite humorous, it’s packed with serious political commentary. For instance, the village priest comments, “Do whatever you want, as long as you say you want to be a part of Europe. And then you’ll get away with anything. Look, the Albanians do God knows what. They sell weapons and women, they take hostages. And the world forgives them, as long as they’re pro-Europe and pro-NATO. They’ll forgive us, too. That’s the trend in today’s world.” Is this where Moldovans find themselves today, with pro-Europe pressure, on one hand, and pressure from Russia, on the other? For instance, your novel seems particularly timely in light of December’s news reports of Ukrainian protests. Like other post-Soviet states, Moldova seems caught between the new Europe and Russia. Moldova needs what Europe has to offer, but Russia can literally freeze out Moldova by cutting off the winter gas supply. Are many literary writers writing about this?

MJ: Let’s address the more scathing side of the novel. Though quite humorous, it’s packed with serious political commentary. For instance, the village priest comments, “Do whatever you want, as long as you say you want to be a part of Europe. And then you’ll get away with anything. Look, the Albanians do God knows what. They sell weapons and women, they take hostages. And the world forgives them, as long as they’re pro-Europe and pro-NATO. They’ll forgive us, too. That’s the trend in today’s world.” Is this where Moldovans find themselves today, with pro-Europe pressure, on one hand, and pressure from Russia, on the other? For instance, your novel seems particularly timely in light of December’s news reports of Ukrainian protests. Like other post-Soviet states, Moldova seems caught between the new Europe and Russia. Moldova needs what Europe has to offer, but Russia can literally freeze out Moldova by cutting off the winter gas supply. Are many literary writers writing about this?

VL: I think Moldovans would like to be pressured by Europe or Russia. In fact, they are not wanted. This is not Ukraine, with rich mineral sources, and not the Baltics, with strategic seaports. We are talking about a place that has never been habitable. Moldova filled with people only in the Soviet period when the federal government of the USSR uploaded investments to create Moldova as a “showcase Soviet store.” Fortunately, the USSR fell apart. Now everyone is free to live as they choose. However, this is a problem for people with the mind-set of teenagers, and Moldovans are not only a very talented but also a very infantile nation. They are not willing to pay for their freedom; they need a mummy to make scandals and shoot a couple of dollars to the party. Now they see Europe as the performer of this role. I don’t blame them for it. This is childish behavior, and God is their judge.

This is not the same situation as in Ukraine. Ukraine is a part of Russia, where the new nation is just beginning to emerge, the nation that is artificially created from southern Russians. Perhaps in a hundred years the Ukrainians will appear, like the Americans came from the British. The paradox is that Moldovans (or Bessarabian Romanians, as they often call themselves)—in contrast to the Ukrainians—are an existing ethnicity. Due to lack of political background, they will never have their own state. Ukraine is needed to deprive Russia of the territory. Moldova on the map of the world is not needed by anyone; it appears like exhaust smoke from burned gasoline. As I mentioned above, Moldova is frantically looking for someone to resolve all Moldavians problems. Romania, Russia, the EU, the US . . . Who will give money? No one gives it. The media reports Russia wants to “block gas," but this is guff. Russia is ruled by people for whom money is the most important thing—they are true capitalists—they do not care for anything, only profit. And they just want Moldovans to pay for Russian gas. It's not so much, right? I don’t really understand what Europe has to offer Moldova as an independent state. Tourists traveling without visas? They don’t need that; they need jobs. It is obvious that Moldova is a failed state. It would be more honest to incorporate Moldova into Romania and stop torturing the Moldovan people.

I say all this not as a resident of Moldova but as a writer: I am absolutely not interested in such things. They’re storms in teacups. All these people who are now tearing each other’s throats out—Ukraine/Somalia/Burma/anywhere—they will be dead in fifty years. And shadows of the clouds will lay—like waves on the sand—on the cemeteries where all these people will be buried. I’m interested in the important and eternal things: love, betrayal, death. Or the clouds. That’s why political moments in my books are no more than a sideshow. Spices but not a dish.

MJ: I’ve read that Moldova is a “major starting point for the trafficking of sex workers.” Why, would you say, this is?

VL: I have a very simple explanation. People don’t have work. Thus, they need to sell the last thing they have: men—their hands, and women—their vaginas. Or internal organs: in Moldova there is a whole village whose inhabitants specialize in selling their kidneys. The whole village lives with one kidney—just imagine. The episode of the novel, where Ion raised a pig from which he hopes to sell transplanted kidneys, rather than his own, has a connection to reality.

MJ: Are writers in Moldova free to write what they choose without fear of punishment?

VL: Of course they are free, because they aren’t published here. Besides, nobody reads Moldovan writers’ books. However, it’s cool. When you live in a banana republic, the State is dangerous. In 2010 I was called several times for questioning by the Prosecutor General’s Office of Moldova for my novel The Good Life Elsewhere. The investigators told me the text seemed "anti-state and offensive to Moldova.” Like a couple of my other stories. I was released after several hours of talks in a small room with barred windows. Then the state’s power changed once again, and they didn’t care about me. As you can see, we are progressing in democracy.

MJ: In a 2004 census, 60 percent of Moldovans cited Moldovan as their mother tongue; 11 percent, Russian. Others speak Polish, Romanian, Ukrainian . . . What is your mother tongue?

VL: The language here is Romanian (Moldavian is a dialect of Romanian). My native language is Russian. The reason for this is not even in my family’s story: although we’ve lived in Moldova for five generations, my father’s family was from Belarus (western Russia), mother’s was from New Serbia (a region of Russia where fugitive Christians of the Ottoman Empire were settled by the government of the Russian Empire). In the Soviet Union, only Russian played the same universal-language role as Latin in the Roman Empire or English in the United States.

MJ: Do most Moldovan writers write in Russian?

VL: In Moldova, writers write either in Romanian or in Russian. I suppose 50/50. It does not matter, though, because their books are not read here.

MJ: In the twelfth chapter, Consul Buonarotti at the Italian Consulate says of Moldovan immigrants, “They’re like spiders. They’ve invaded and now you can’t do anything about them.” Is this simile a representation of the typical response Moldovans receive when they immigrate to Italy?

VL: This is a typical reaction of any man toward the influx of illegal immigrants in his country. We can judge this reaction well or poorly, acceptable or not, but it is what it is. Nobody wants rivals. To honor Moldovans, I would like to say that they never set their own rules and that they prefer to play by the rules of the country where they arrived. This is an ideal nation in which to be an immigrant. Again, I do not see anything specifically Moldovan in this phenomenon. Each year in the United States, thousands of young people pack their bags and head off to conquer New York City, Los Angeles, etc. instead of creating their lives at home. How do they differ from the heroes of my book?

MJ: Before we end our conversation, could you recommend three or four Moldovan writers—both some that have been translated into English and others that have not but most urgently should be?

VL: I am happy to recommend two excellent Romanian writers from Moldova. They are brothers Mihai and Alexandru Vakulovski and a great poet, Vadim Lungul, who writes in Russian. I’m not sure whether they have been translated into English, but they deserve to be. Katia Kapovich, who now lives in the US, is a great Russian poet from Moldova. She writes in Russian and English. Who else? Well, I am pleased to recommend myself.