Mirza Alakbar Sabir: An Azerbaijani Poet-Satirist in Translation

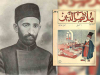

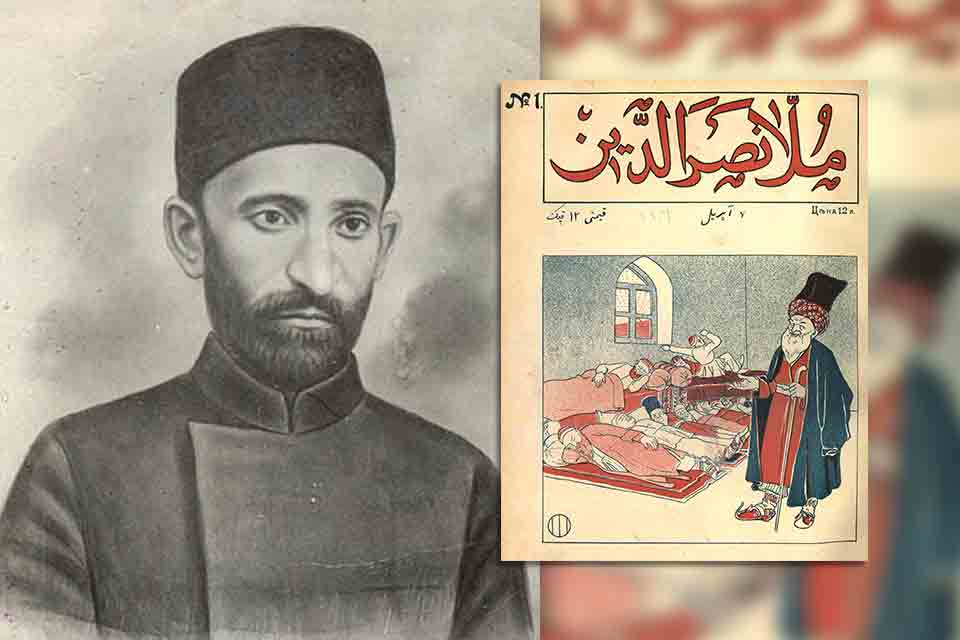

The satirist and poet Mirza Alakbar Sabir (1862–1911) is one of those prominent voices known to everyone in his homeland, Azerbaijan, yet to only a few abroad, especially in the English-speaking world. In his works, Sabir called for enlightenment among the ordinary people and criticized the corruption of politicians and religious clergy. His poetry collection, Hophopnameh (after his pseudonym “hophop”), was compiled and published posthumously in 1912 by his friends and colleagues.

The most widespread English translation of Sabir’s poetry was published in 1969, when Dorian Rottenberg translated some of his poems for an anthology titled Azerbaijanian Poetry (Azerbaijani is the correct modern term). The anthology does not, however, include the poems translated here. Most other translations of Sabir’s works appear in the context of academic articles in which the translations are literal, not literary.

Sabir’s most significant work was created after 1909, when he began writing for Molla Nasreddin. This satirical magazine published works in the Azerbaijani Turkic language instead of Persian, which many writers and elites used at the time. Molla Nasreddin’s writers addressed topics such as politics, religion, lack of education, and women’s rights. The speakers in Sabir’s poetry are not figures of identification; he often appropriates the voices of people he criticizes to point out how absurd and harmful their perspective is. Indeed, one important aspect of translating Sabir is preserving this tone and allowing satire to emerge as a natural consequence of allowing the speaker to voice delusional thoughts. For example, “No school, I said! Get off my back!” (Oxutmuram, əl çəkin!) is written from the perspective of a father who refuses to send his son to school, convinced that education goes against religion. This poem parallels Sabir’s life, as his father disapproved of his academic and literary ambitions and wanted him to take over the family grocery store.

Sabir often appropriates the voices of people he criticizes to point out how absurd and harmful their perspective is.

Sabir structures his poems around a memorable refrain, with each stanza building toward a variation of that refrain. He uses rhyme to first lure readers into the poem’s comfort and familiarity and then, staying within the rhyme, surprises them by revealing the speaker’s misguided convictions. The central role played by rhyme in both the style and satire of Sabir’s poems adds challenge to translation. The Azerbaijani language allows for fluidity and frequency of rhyme, thanks to its endless grammatical suffixes (e.g., the suffix -dir means “he/she/it is”). This is hard to reproduce in English, where rhyme usually occurs among different lexical items (red, bed, head, dead). The translator undoubtedly needs to re-create the original musicality in translation.

In the early twentieth century, the territory of modern Azerbaijan was a part of the Russian Empire. As in many regions of the world, Azerbaijani people also experienced a growing demand for social and political changes. Sabir’s poetry reflects these frustrations and defiance of a society yearning for change. Despite being written over a century ago, his writing maintains its relevance in today’s world (and, arguably, still will in the future). Just as Sabir strived to make his poetry accessible to the people of his time, today’s translator must keep the author’s intentions in mind, allowing the text to sound culturally foreign while preserving its accessibility.

Three Poems

by Mirza Alakbar Sabir

No school, I said! Get off my back!

I’m the parent. I decide. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Won’t let you brainwash my child. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Although this silly boy of mine is crazy about reading,

Although his mind is somehow drawn to scientific thinking,

I think all these godless schools indulge the youth in sinning.

It’s faith herself you have defiled. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Won’t let you brainwash my child. No school, I said! Get off my back!

After all, he’s still so young: he can’t tell good from evil.

This talk of science got him hooked. It should be made illegal.

A boy who listens to his father rises like an eagle.

My son brings only shame, no pride. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Won’t let you brainwash my child. No school, I said! Get off my back!

I won’t have mercy for his tears. Let his eyes turn red.

Look at his older brother. He’d beat a guy who touched his bread.

I’d sooner see him die than put that square hat on his head.

You disbelievers, step aside. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Won’t let you brainwash my child. No school, I said! Get off my back!

How is this any of your business?! You’re acting like the kid is yours.

Who let you rule over me as if you’re my rider, I’m your horse?

No education means no progress — the words I simply won’t endorse!

I won’t repeat myself. Goodbye! No school, I said! Get off my back!

Won’t let you brainwash my child. No school, I said! Get off my back!

A son should take after his father, not some liberal fools.

He should learn his father’s craft and how to use his father’s tools.

I asked an expert friend of mine if he would send his son to school.

He asked me if I’d lost my mind. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Won’t let you brainwash my child. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Enough! Go burn in hell. Your lies won’t bring me to your level.

For the last five years now, you’ve been meddling with the devil.

Because of you, my dear son acts like a heathen rebel.

To hell with fables you’ve compiled. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Won’t let you brainwash my child. No school, I said! Get off my back!

I’ll never sell my soul to you — a bunch of tricksters and tramps.

I’d sooner dig my son a grave than let him sit for your exams.

Don’t talk to me about your school, a school of swindlers and scams!

Run from the fire. Run like wild. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Run from the fire. Run like wild. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Won’t let you brainwash my child. No school, I said! Get off my back!

He knows enough; in fact, I wish his head were emptier.

He’d look much happier than now if his thoughts were healthier.

He must do business like the rest. How else will he get wealthier?

He must keep money on his mind. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Won’t let you brainwash my child. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Don’t want to waste my breath on you — not a single sigh.

I know you’re going straight to hell, but not with my son by your side.

Stop calling yourself Muslims; you’re the Devil’s spies,

Traitors to your own kind. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Won’t let you brainwash my child. No school, I said! Get off my back!

It’s faith herself you have defiled. No school, I said! Get off my back!

Doesn’t Bother Me

The nation’s rotting inside out. Doesn’t bother me!

The traitors plot within our crowd. Doesn’t bother me!

I keep my stomach full. Why bother with the fools?

Oh, let the whole world get wiped out. Doesn’t bother me!

Shh! Quiet, keep it down. The sleepers will wake up.

I won’t allow the unawakened to be woken up.

If one awakens, thin and hungry, may God keep me plump.

My house is clean for all I care. The world’s my garbage dump.

The nation's rotting inside out. Doesn’t bother me!

The traitors plot within our crowd. Doesn’t bother me!

Stop talking about history. Don’t stir up the past.

Don’t bring up other nations or the laws they’ve passed.

Let me enjoy my dolma. I want to eat at last.

Who cares about tomorrow? Life passes by so fast.

The nation’s rotting inside out. Doesn’t bother me!

The traitors plot within our crowd. Doesn’t bother me!

The nation’s child may beg and bow like a whining pup.

Filth and poverty — enough to fill their empty cup.

Widows going homeless? Well, they better toughen up.

There’s a party at my house. Don’t even dream of showing up.

The nation's rotting inside out. Doesn’t bother me!

The traitors plot within our crowd. Doesn’t bother me!

Every nation dreams about prosperity and progress.

In their homeland — day and night — they work toward progress.

If it got lost in my warm bed — this thing called progress,

I promise once I find it, we’ll make some progress too!

The nation’s rotting inside out. Doesn’t bother me!

The traitors plot within our crowd. Doesn’t bother me!

Don’t Move, for God’s Sake, Baby, Stay in the Dark

Don’t move, for God’s sake, baby, stay in the dark.

Close your eyes, stay ignorant, stay in the dark.

Hush, little baby, hush.

Go back to sleep, now hush.

Don’t wake up — the real world’s a tragedy, alas!

If only day was just as sweet as night, baby, alas!

The sleepless must embrace insanity, alas!

Put your head back on the pillow; sleep safe and sound.

Hush, little baby, hush.

Go back to sleep, now hush.

Your open eyes will only show you suffering and pain.

You’ll see how people drenched in grief are perishing in vain.

You’ll see abuse of power, so corrupt and inhumane.

Snuggle up in a warm blanket, baby, don’t wake up.

Hush, little baby, hush.

Go back to sleep, now hush.

If you wake up for a second, save your life — go back to sleep.

Take your theriac, your opium, smoke your weed — go back to sleep.

If your right side’s stiff and sore, roll to your left — go back to sleep.

Don’t abandon good old habits, sleep baby, don’t wake up,

Hush, little baby, hush.

Go back to sleep, now hush.

Sleep the light into your dreams, don’t you let them slip away.

Not a minute, not a second, don’t you let them disobey.

Sleep into oblivion, sleep so you forget your name.

When the Sun falls to the earth, sleep amid a world in flames.

Hush, little baby, hush.

Go back to sleep, now hush.

Translations from the Azerbaijani

Editorial note: Mammadova’s translations won the inaugural OU Student Translation Prize in the poetry category in 2025.

Mirza Alakbar Sabir (1862–1911) was an Azerbaijani poet and satirist who lived under the Russian Empire. The highlight of his writing career was his joining of the satirical magazine Molla Nasreddin. The magazine covered topics such as politics, religion, lack of education, and oppression of women. Sabir’s poetry collection Hophopnameh was compiled and published posthumously in 1912 by his friends and colleagues.