There Are Things to Remember: Translating the Poetry of Giovanni Raboni

In memory of Giovanni Raboni & Vinio Rossi

1

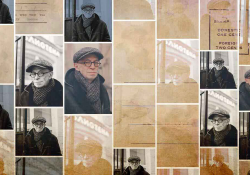

Some thirty-five years ago, the guest-presenter in my translation workshop at Oberlin College, Vinio Rossi, a dear friend and colleague, introduced us to the poetry of Giovanni Raboni (1932–2004).[i] Asked to bring a short text, given the constrictions of the course, Vinio began with brief remarks about major issues of translating from Italian and Raboni’s work in general, against the background of Italian literature. He then handed out “the literals” to the first section of “More Interviews,” a five-part sequence, the others of which are entitled “The Washerwoman,” “Surgeon,” “The Fortune Teller,” “The Baker”:

The Carpenter

If you seek

you find. If you want to save some wood,

instead of nailing it into a square

or an isosceles triangle or a circle,

you can make it into a cross.

When Vinio was alive, during one of our cocktail hours at Presti’s bar, we’d always get back to the immediate aftermath: after Vinio had finished walking us through the literals, a student in the front row crossed herself dramatically, then burst into tears and asked to be excused. Only later did we learn she’d been having a crisis of faith, and thanked us after our co-translations were published for connecting her with “a deeply Catholic poet.”[ii]

Vinio was instrumental in helping us launch Charles Wright’s Montale translations in the Field Translation Series, knew of Raboni’s debt of gratitude to Montale, his several books of poems that were making an indelible mark, and his stellar career as a translator as well. So over another glass of Presti’s best chianti, knowing I’d been collaborating on translations of several European poets, Vinio proposed writing to Raboni about any interest, inasmuch as it seemed very few of his poems existed in English, in our trying to collect enough for a Selected. Not only did Raboni write right back, he said he’d be delighted to set aside some time if we wanted to get to Milan so we could say, he joked, “the translations have been approved by the author!” As it has in other blessed instances, Oberlin College generously provided a travel grant, Vinio booked us on Al Italia, and next thing we woke up in Rome, eventually making our way to Raboni’s door in Milan after a quick trip to Bologna. Vinio had been corresponding with Alfredo Rizzardi, a professor and something of a dean at the university there, whose work he’d been following and translating ever since he came across some early Rizzardi poems, in English! They’d appeared in Poetry, which we found intriguing.

What a way to get over jet lag: bask in the delightful, generous, otherworldly company of “Alfredo!”: after wining and dining us sumptuously in Bologna, he zipped us in his little roadster up to Urbino, where he also taught, having arranged for us to give a talk on co-translation to a gathering of literature students. En route, he stopped for gas. “ALFREDO!” shrieked the woman working the pumps when she recognized him, threw her arms around his neck, and whispered what sure seemed like sweet words, first in one ear, then the other.

“Why don’t you also call me ‘Alfredo’ from now on,” he grinned.

After wining and dining us sumptuously in Bologna, Giovanni zipped us in his little roadster up to Urbino, where he also taught, having arranged for us to give a talk on co-translation to a gathering of literature students.

Thanks to Vinio’s virtually native Italian, we somehow bumbled our way through the talk we’d not taken sufficient pains to organize. While attending to university business, Alfredo had turned us over to his chief assistant, a graduate student of sorts at the time. It’s no surprise, as I google Gabriella Morisco now, to see what an impressive scholar she’s become, with special expertise in American and English literature. She dazzled us with her range of reference, incisive comments on things literary, and her English likely had a deeper vocabulary than ours.

As if to make up for not having attended our talk, Alfredo invited us for a nightcap at his lodge on one of Urbino’s hills. Aware of Field magazine’s use of postcards for covers, after quite a few brandies he pulled something of a shoebox down from a shelf in the library and wondered if we’d like to “use” one for a future magazine cover. As if reading a card catalog, we flipped through the astonishing collection: mostly cards actually penned by writers, among them the card we eventually chose for a possible Field cover: James Joyce’s handwritten card sent from the Zurich Zoo to his grandson Stephen, then five years old, living in Paris. “I’ll only charge you $200 for a one-time use, but you’ll need to insure it for $1,000 when you send it back,” Alfredo said, topping off our snifters with a decent local cognac. We’d not have gasped if we’d known the Joyce-card/Field issue would sell out, surely thanks to the card’s provenance—Field covers had already become something of a collector’s item!—and especially for his charming, invented tale about what the three monkeys in the image are up to, sitting at a table and slurping soup.[iii]

Inserting the card into a padded envelope, Alfredo handed it to Vinio with some remarks in Italian I missed out on, which Vinio couldn’t later recall due to a few too many passes at the cognac bottle, he pleaded. Though not a Field editor, hence with no authority, Vinio, typically generous beyond the call of duty, urged Alfredo to send some poems to Field so they could perhaps appear in the same issue bedecked by the JJ card. I quickly added of course we’d be happy to “consider” any he’d like to try us out on. . . . Generously driving us to catch an early train to Milan the next day, Alfredo said to be sure to greet Raboni for him.

As if reading a card catalog, we flipped through the astonishing collection: mostly cards actually penned by writers, among them the card we eventually chose for a possible Field cover: James Joyce’s handwritten card sent from the Zurich Zoo to his grandson Stephen, then five years old, living in Paris.

2

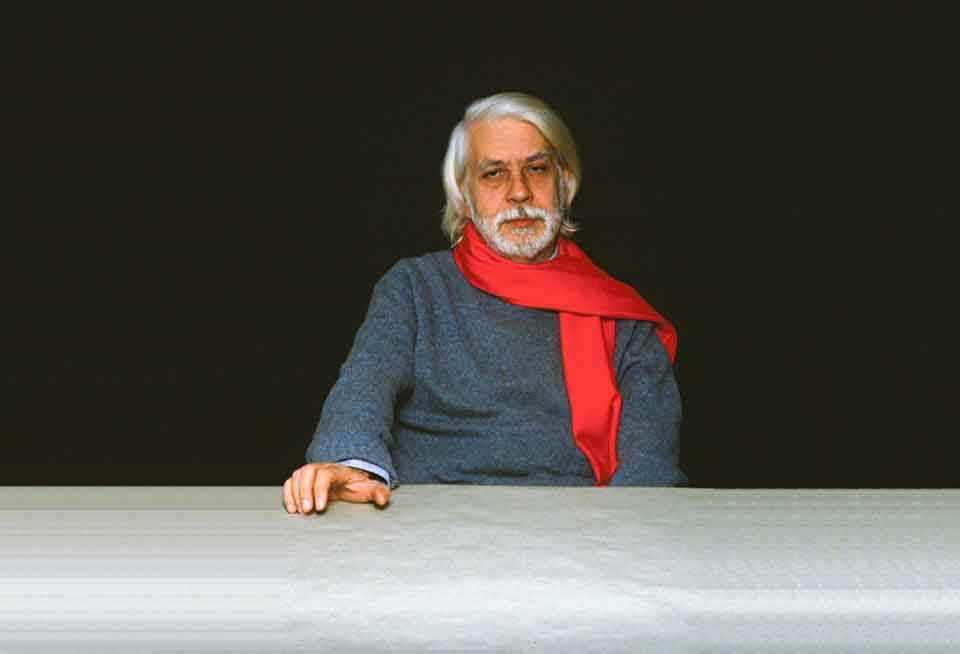

We called Raboni from the Hotel Milano Scala, where he’d booked us a room for only $99 a night, though the price list on the door said $239. We figured he had connections, which he didn’t deny; as he wouldn’t, for future “breaks” we enjoyed during our stay. “Let’s use first names,” he said, before advising us to keep the large windows in our room open as much as possible to hear any strains from an opera at La Scala close by, which especially gladdened Vinio, a huge opera fan. The shank of the evening still ahead, Giovanni suggested we soon meet in the cozy, beautifully appointed cocktail lounge at the hotel, where he said we wouldn’t mistake him for one of the opera singers who hang out there. “I’ll be an older guy, quite slight, with a scruffy mustache and beard my friends say makes me look even more wigged than usual. But you won’t be able to yank them off,” he laughed, alluding to the Carole Lombard and Jack Benny film, To Be or Not to Be, a favorite we shared!

Waiting for Giovanni, we were sipping aperitifs in the lounge when suddenly the double doors burst open, and in strode a large figure dangling something of a large white handkerchief from his hand, followed by a wedge of an entourage, marching to his tune, and headed to a more private lounge in the back, set off by heavier doors. “Guess who just walked inches by us,” Vinio said, and didn’t wait for an answer because it was clear I didn’t know. “The great Pavarotti, that’s who! In my younger years, I’d have schemed to get his autograph.” Vinio reminded me we’d seen Pavarotti’s picture on a poster tacked to a kiosk. If I’d kept better notes, I’d mention the opera.

Spotting us before we caught sight of him, Giovanni waved the small wave one does to children, and eased into a leather armchair across from us. We began with a toast to “a possible collection of his selected poems.” Tenting his hands, he promised to vet all translations, now and by mail once we returned, as well as help clear the rights to translate. No email back then, so we understood the endeavor would take considerable time, especially given our day jobs; his as an editor for Mondadori, still one of Italy’s premier publishing houses. A superb translator himself, he was also devoting himself to a number of his own alliances with foreign poets whose work he wanted to ferry into Italian, as well as “getting after” his own poems. We gave him a copy of questions we had about the versions we’d brought for review, which he took time to pore over before raising his glass a last time and folding the sheet crisply, tucking it into his jacket pocket as if it were a handkerchief. Clinking glasses one last time, he proposed we take a day or two just to be in one another’s company, get a “feel for each other’s predispositions, how we shared the same air” (almost an exact phrase from one of his poems, Vinio and I realized and shared a nod); “and I trust you’ve got sturdy walking shoes,” he added. “I’d like to tour you around the landscape of some of my poems,” he said softly, without a trace of self-importance.

We should have trained to be the walking companions of Giovanni, who taking tinier steps soon left us gasping a yard behind. Our tongues hung out every time we passed espresso bar, but mindful of having asked for precious time of one so engaged in the literary life of Milan—not to mention Italy and other lands as well—we didn’t beg for mercy, just doubled down on espressos when Giovanni finally said it was time to drink something. He led us to the “establishment” of a friend, who simply tore up the bill when we went to pay.

We’d written in our introduction to The Coldest Year of Grace that Giovanni’s poems “seem at times spoken by a prosecuting attorney building a case against waste and corruption in secular and religious circles.” Leading us through the landscapes, he seemed a sort of modern-day Virgil. Given his eye for searing detail, you wouldn’t want to face him as a defendant he was prosecuting before a jury. When Giovanni saw I had something of a sketchbook going—I’d laid it on the bar’s table—and learned I especially wanted to bring back images of churches for my wife, he suggested I might want to do a quick “portrait”—a favorite word—of the defunct square bordered by the church of San Lorenzo and a porno movie house. We then moseyed on to the Naviglio, a large basin fed by a canal he’d fished in as a lad. “No one of right mind would eat anything caught there now, of course,” he grinned. “It’s a Lethe no one ever gets to the other side of.”

What began to strike us was the concordance between the voice of his poems and Giovanni’s natural way of speaking. Both voices shared a similar sharpness of silence, a way of breaking off into fragment and allusion, half turning away from both subject and object, to focus, not only on what is essential, but equally what must be ignored, or suffer oblivion by drowning in the inconsequential. Catching us flagging with a sudden glance back at us, Giovanni broke off the tour: “Let’s take tomorrow as well to enjoy each other’s relaxed company before we hover over the poems in my cramped study. Some friends are helping restore The Last Supper and will let us watch a bit, if you don’t mind sitting on some splintery planks and getting a fine coating of dust, not to mention some in our lungs!”

What began to strike us was the concordance between the voice of his poems and Giovanni’s natural way of speaking. Both voices shared a similar sharpness of silence, a way of breaking off into fragment and allusion.

Ecstatic at the prospect, we assured him our behinds had trained aplenty sitting on bleachers at sporting events. We promised to return the favor if he’d do us the honor of appearing at Oberlin at some point. “Something else to drink to,” he said when steering us back to the hotel, joining in a salute to Pavarotti on his kiosk.

All my bones and muscles still recall the grooves and bumps and, yes, splinters, in the plank as we watched the crew restoring The Last Supper: imagine sitting for some three hours as in an upside-down operating theater, watching three souls poised high above on ladders, a woman and two men in white lab coats, who’d daily, excruciatingly, painfully clean an area the size of a postage stamp with delicate instruments carefully laid out on a tray on the ladder’s side-extension, attended by others in gray lab coats below ready to assist with any request. At one point, I had the temerity to nibble on a dry roll I’d stashed in my pocket to head off an occasional siege of hypoglycemia, only to have the whole theater shut down and everyone look my way. Giovanni politely helped me brush some crumbs off the plank into my handkerchief, morse-coding me with pats on my knee: n-e-v-e-r-d-o-t-h-a-t-a-g-a-i-n-p-l-e-a-s-e. On the way out, he whispered that any such sound as I’d made could easily be taken for something fluttering down from Leonardo’s brushstrokes.

Our nerves a bit frayed, Giovanni asked if we’d mind taking a shortcut back to the hotel through Musocco, the cemetery where his father was buried, whom he’d not visited in some time; and where, as he’s written in “The Baked and the Raw,” room is made by stacking the dead one on top of the other, sealed in a piece of wall. They move one section after another, he said wistfully. “This month it’s section 49, where my father lies.” Looking up at a stack of slabs, Giovanni pointed to his father’s, its plaque dull in the slanting sun’s rays, his father’s name clearly in need of polishing—something he liked doing himself. He was, however, so tied up in projects, he sighed, that he’d perhaps have to tip a groundskeeper to ladder up and give it a shine. To give Giovanni a moment alone, Vinio motioned me back a few steps. We turned up our collars against the dusk’s chill while watching Giovanni slightly sway back and forth as if in a reverie. Noticeably slowing down for the last stretch back to the hotel, he split off when it was clear we could find our way back alone. “Get a good night’s sleep for what you’re in for tomorrow,” he said matter-of-factly.

3

Well aware of Raboni’s reputation as a translator himself—his Baudelaire and Proust versions were widely celebrated—we knocked on his door the next morning with some trepidation. Having graduated to a warm hug, we were led into his study, a mini-museum of paintings and sculpture. His elegant desk, piled high with journals and books—he was known for his interest in young writers—looked out on a small park with bountiful trees. A quiet place to read and think, what an ideal, interior space to find your way to soft-spoken poems. “Speak from a distance or just be quiet,” Raboni took as an epigraph from La Fontaine’s Fables.

What he emphasized again and again was to locate the voices of the poems, making sure that they don’t sound “translated or stiff: I want the poems to live in your American English. Make sure they read naturally, spoken by an actual human being!” So much of the rest of our time together consisted of him reading us the originals to fine-tune Vinio’s hearing them deeply, as he was my conduit into the sounds of their music; and my reading what we’d come to back home while Giovanni and Vinio listened for any slips and slides to the voices. In the days left, Giovanni also cleared up a few passages where we’d gotten lost and kept reassuring us that we were tracking the poems like well-trained bloodhounds, whose trainer of course he was in spades.

Well aware of Raboni’s reputation as a translator himself—his Baudelaire and Proust versions were widely celebrated—we knocked on his door the next morning with some trepidation.

Finally, the day before departing, we relaxed over a final toast to “us three monskeyteers.” (We’d shared the Joyce card with him.) All the questions we’d come with, as well as others that came up while working together, Giovanni answered more deeply than we’d bargained for. More importantly, we’d apparently gained his trust; and knew he was now committed to making sure we’d eventually have a viable manuscript to circulate, so worries something might go amiss gradually ebbed. He sent us back to the hotel with a final surprise: “I’ve arranged a small dinner later tonight, invited a few friends I’d like you to meet, so I’ll pick you up around eight. No need to rent a tuxedo, or even polish your shoes: just come as you are!”

Again, if I’d only kept better notes! If Vinio were alive, he’d surely know the name of the restaurant Giovanni seemed to have reserved for our final “banquet,” as the dozen of us gathered to wine and dine, and then wined some more past midnight, without any other patrons in sight. Though Giovanni introduced us at some length to the other guests, whose own accomplishments he enumerated as if presenting them for an award, all I recall is that they were prominent writers, artists, and editors. Having had way more to drink and eat than usual, all that’s left now is a blurred image of the night’s parameters. And if only a tape had been made of final remarks, especially Giovanni’s and concluding with Vinio’s “thank you” back, delivered in his best Italian! Knowing he’d likely be asked to say something too, Vinio had gone to the lounge at the hotel to write out his remarks. If Vinio had stuck to the script, like a good politician who’s taught to “stay on message,” I’d not have much more to add. However, to this day, I’m told, people still talk about Vinio’s slip of tongue, which brought the house down. Everyone laughed so loud and so long, tears came streaming forth as well, so that even I joined in, with absolutely no clue of what Vinio had said to prompt the torrent.

No one said anything else of any real moment, I recall, just kept exchanging laughs till they died out as well. Driving us back to the hotel, Giovanni kept telling Vinio something, patting him on the arm, as if to say, it seemed, “Don’t beat yourself up”; as Vinio’s expression, frozen from the moment the laughs began, remained distraught. I knew enough to wait till he might be willing to recount what had happened, about an hour into our flight back.

“Okay, keep your seatbelt buckled,” Vinio began. “Remember the dessert? Well, a friend of Giovanni’s had specially brought figs from his grandfather’s farm for the centerpiece, about the choicest figs you’d ever eat; not to mention what the pastry chef would do with them.” I did sort of recall I’d never quite had anything like them. “Well, in the middle of my little thank-you speech I thought it might be amusing to end on a note of what a beautiful dinner we’d been treated to, and what a finishing flourish, the ‘figa’ concoction. . . . Sober, I damn well know the Italian for ‘fig,’ and it sure ain’t ‘figa’![iv] I’m leaving it at that. Your Italian might find it useful for other contexts, when you get around to adding it to your vocabulary.”

Oberlin, Ohio

[i] Some time before, David Young had come across Raboni poems in an anthology and passed them along to Vinio Rossi and me.

[ii] The Coldest Year of Grace: Selected Poems of Giovanni Raboni (Wesleyan University Press, 1985).

[iii] Translated by Vinio Rossi from the Italian, here’s what Joyce wrote to his grandson:

6 April 1937

Caro nipotino: These are the 3 monskeyteers of Zurich. Their names are Athos, Porthos and Aramis. Porthos is in the middle and he makes the most noise with his soup. Athos is on the right and he put away 2 spoonfuls to the others’ one. But Aramis on the left says soup is for saps and what he wants his un singeno di coco.

Such are monskeyteers

NONNO

In the note at the end of the Field issue, Vinio adds that while the postcard appears in the collected Letters of James Joyce (ed. Richard Ellmann, 3:395), there are two errors of transcription: “songs” for “soup” in the third sentence, and “not” for “un.” “Caro nipotino” means “Dear little grandson,” and “NONNO” means “Grandpa,” but “un singeno di coco” is anybody’s guess! Ellmann bravely hazards “A simiana (?) of ‘cocoanut.’” Rizzardi wrote us adding, “As to coco (cocco), and the meaning of the sentence, I think it’s a conventional play language coined by Joyce and his grandson—arbitrary, ununderstandable—or at least I don’t succeed in making sense of it. Coco sounds like ‘cocco,’ i.e. Tesoro, honey, darling, in speaking to a child.” Back at Oberlin, when Vinio and I met with Oberlin’s comptroller, we were at some pains to justify the $200 expense for the card. Listening patiently as we agonized, the princely Arthur Cotton finally shooed us out the door. “Let’s don’t ever do that again, boys,” he pretended to scowl.

[iv] If readers Google “figa,” they will, I hope, understand why I’ve not translated it.