Translating Zhu Zhu: Poetry as Lifeline

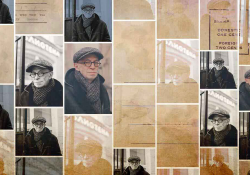

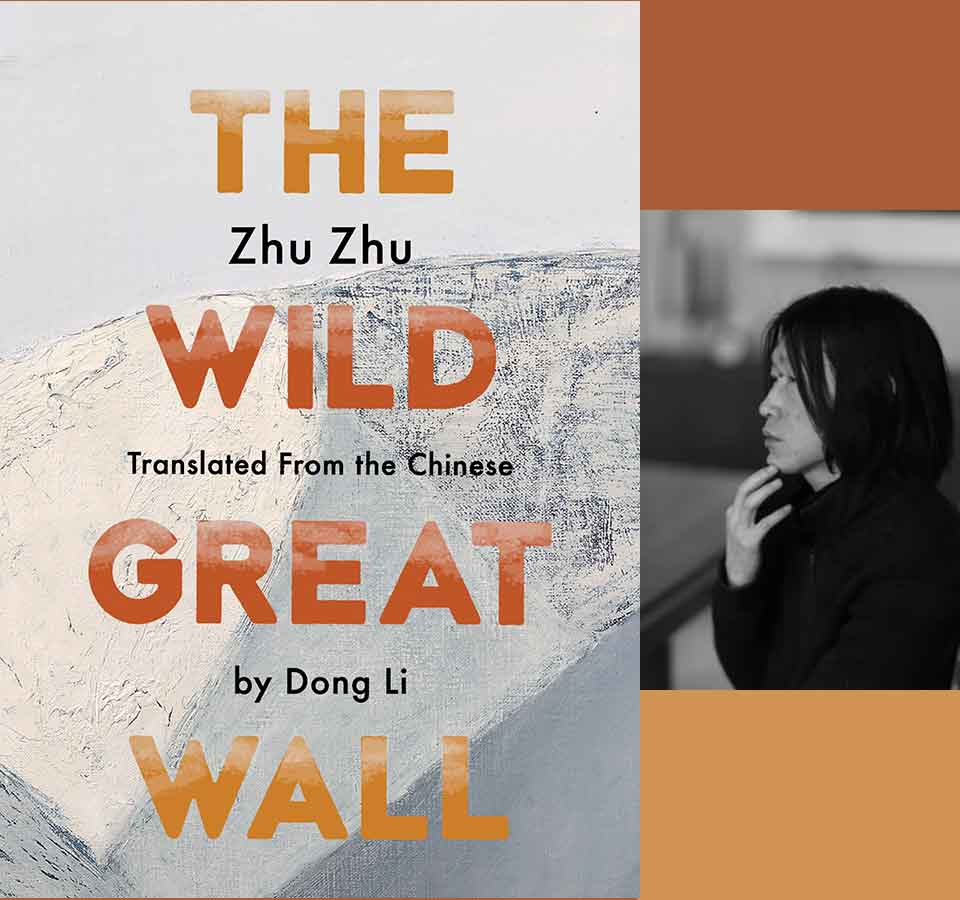

Born in Yangzhou and currently living in Beijing, Zhu Zhu is the author of numerous books of poetry, essays, and art criticism. The Wild Great Wall, recently released by Phoneme Media, is a selection of his work spanning 1990 to the present. Here, translator Dong Li looks at the work of this “lone wolf utterly on the periphery” of contemporary Chinese literature.

I first came to know Zhu Zhu’s voice on a New England winter day over a transpacific phone call that lasted a whole night. I wanted to translate his poems and needed permission. As the tone of his voice shifted from distanced skepticism to understated enthusiasm, we felt the trust, and it dawned on us that this trust could be extended to a book. That’s how everything started and our friendship began.

I kept thinking of his soft and resolute voice as I gathered his books and plunged deeper into winter and into his world.

Long long winter,

a wolf looks for the forest of words.

These two lines seem to encapsulate Zhu Zhu the poet: a lone wolf utterly on the periphery with his treasured independence, as well as his unrelenting respect and unstoppable reach for words and their histories. As I selected poems from his robust twenty-five years of poetic output into one slim volume, I was looking at his “forest of words” that slowly both grew on me and accrued meaning with each reading.

As the long winter slowly melted into spring blossoms, as the trajectory of Zhu Zhu’s poetic arc became clearer before my eyes, I was about to match the face to his familiar voice. I met him for the first time when he came to the United States for a joint residency at the Vermont Studio Center. With an almost reticent demeanor, he quietly blended in. I remember at meals he always wanted to take a seat by the window, where the Gihon River could be heard. I often traced a trail of cigarette butts to find him sitting on the porch or by the Gihon, wreathed in smoke. I never saw him scribble down his impressions of the country or the residency, but toward the end of our time together, a stack of loose pages was slipped under my door. It smelled of burning.

Over time Zhu Zhu’s outlook has become more international, but he returns again and again to classical tales and historical figures and investigates their relevance to our times.

After China’s political upheaval in recent eras and the continuous capitalist frenzy, the “warm and languid routine” of a foreign writing residency did not seem to suit Zhu Zhu, as I often found him spinning and smashing at the ping-pong table or in one of the two bars in the village drinking away with the locals, communicating through his gestures and smiles. Over time his outlook has become more international, but he returns again and again to classical tales and historical figures, “brimming with unfinished crying,” and investigates their relevance to our times. His narrated and narrative histories are not “dressed as literary allusion / blending allure into parable” but are meant to be “a scalpel-like nib, to open / the chest of old China.” Even his more politically charged poems are not meant to take sides but to reflect a layered and nuanced aesthetic reading of history and politics. The poems remain open and resist easily reductive interpretations.

not to become a ghost, not to traffic in suffering,

but to clarify life’s wellspring—

Not to serve as a loudspeaker for a certain ideology, not to exorcise for sensational effects, Zhu Zhu excavates “the forbidden grounds of memory” by clarifying the ambivalence that a simple political reading might elide. He demands that poetry return to its ancient roots, where words first emerge and find their calling in fragments and lifelines.

Zhu Zhu demands that poetry return to its ancient roots, where words first emerge and find their calling in fragments and lifelines.

Here is a fearlessly independent poet who maintains his cool and observes the world with his whole eyes as the political horizon blurs and shifts. What matters to him is how words silently explode and become explosives, and how language sinks and rises. Here is a poet who advocates poetry as “a pass for the despicable and the noble,” an open field where everyone is welcome to speak up and sing. Here is a poet who reinvents himself from an early ethereal verse limned by the unspeakable, to a visual and visceral composition of images that impart the transient and untranslatable, to restrained and rich narrative investigations of historical figures and phenomena. Here is a poet who looks again to “the mundane and song,” where the lyric finds its first note. This can seem like an indulgence in our profit-reigning attention-splintering age. Yet it is indeed in this indulgence that “sharp spasms of morality” and “endless folds of history” become music, memorable, and memory. It is indeed in this indulgence of poets roaming in word and world, of slow lines shuttling through the problems and prospects of the political, the historical, and the quotidian that poetry resists being reduced to footnotes and instead commands to be read and reread for what it illuminates.

. . . sitting quiet between words,

a man whose life began from a full moon,

always questing for that first moving glance.

It is winter again as I write this note. Our spring retreat in the Vermont country was years ago. As I went through the last proof of The Wild Great Wall in one long breath, these final smoked lines came alive again in Zhu Zhu’s attentive voice. I lament the irretrievable loss of these Chinese words, whose constellation first moved me and sent me on a mission to look for the English words that could approximate the sensory traces and emotional pulls of the original. I feel consoled that the reader can now experience Zhu Zhu in the English language for the first time. As I shift between Zhu Zhu’s Chinese and my English, our shared words, like trees in a forest, seem to grow with each season. Here is a lyric that continues to extend.

Leipzig, Germany

Editorial note: Zhu Zhu’s poem “Old Shanghai” was first published on the WLT blog.