How Literature Saved the Olympics

Upon finishing Chris Cleave’s recent novel Gold (a drama examining the friendship and family of three Olympic-caliber British cyclists), I took to the Web to find other fiction featuring Olympic competition. I didn’t expect what I found: there’s not a lot out there. Or there’s not a lot that wants to be found. In my failure, though, I found something much more interesting: literature and the Olympics enjoy an interwoven, codependent history.

Before we begin, it’s important to get some housekeeping out of the way, even though I suspect this is common knowledge. The Greeks, in their vast wisdom, were champions of both the body and the mind. The poet and the athlete were equally valiant to all. Let’s look at this in context. Imagine a stage where Sweden’s Tomas Tranströmer, winner of the 2011 Nobel Prize in Literature, and Jamaica’s 100-meter world-record-holder Usain Bolt were crowned with olive wreaths and stood side by side to be celebrated.

Or what if Bolt found it absolutely necessary to commission Tranströmer to write a tribute celebrating his many victorious races? That’s a nice image, and it’s a great example of the relationship athletics and literature used to enjoy. After reaching the heights of physical performance, winning athletes weren’t satisfied until an all-star poet penned them to poetic immortality. This is how, as unlikely as it may seem today, the competitions at Olympia became a literary hotbed. Lesser writers were also known to flock to Greece to recite their work over the crowds in hopes of being discovered.

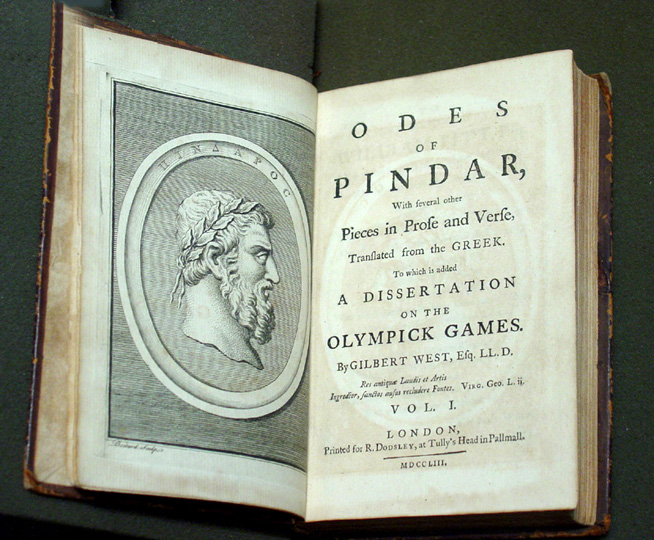

That brings us to Pindar, a prominent member of the nine lyric poets—a sort of dream team of Greek poets deemed worthy of critical study by ancient scholars. It can be argued that Pindar’s greatest legacy is a collection of victory odes; they’re his only complete manuscripts to survive. Here’s an important one, the beginning to Olympian 1:

Water is best, and gold, like a blazing fire in the night, stands out supreme of all lordly wealth. But if, my heart, you wish to sing of contests, look no further for any star warmer than the sun, shining by day through the lonely sky, and let us not proclaim any contest greater than Olympia.

– Pindar, “For Hieron of Syracuse Single Horse Race,” 476 BC

What’s important here, for my purposes, is that while Pindar composed victory odes for many different competitions, he tells us there were no greater contests than those at Olympia. That’s a great blurb from the MVP of victory odes. And he was right, the ancient games reached their peak in the sixth and fifth centuries BC, before being stamped out as the Romans gained power.

Pindar’s influence doesn’t end there, though. In 1833 a Greek newspaper editor, Panagiotis Soutsos, stirred up some interest in reviving the contests at Olympia when he published his poem “Dialogue of the Dead,” which features the ghost of Plato lecturing a financially and politically failing Greece:

Leave your petty politics and vain quarrels.

Recall the past splendour of Greece.

Tell me, where are your ancient centuries?

Where are your Olympic Games?

Did you see what poetry did? The Olympic competitions were dead until this poem breathed life into them. A form of the competitions resumed and interest slowly grew until 1890, when Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the first International Olympic Committee (IOC), which spawned the 1896 games in Athens, the first incarnation of the contemporary Olympic Games.

Also noteworthy, it’s rumored that Robert Browning’s poem “Pheidippides,” the story of the first marathon runner, inspired the IOC to include the marathon in the 1896 games:

So, when Persia was dust, all cried, “To Acropolis!

Run, Pheidippides, one race more! the meed is thy due!

Athens is saved, thank Pan, go shout!

What’s also important about Coubertin was his affinity for the Greek definition of Olympian. “[Coubertin] was raised and educated classically, and he was particularly impressed with the idea of what it meant to be a true Olympian—someone who was not only athletic, but skilled in music and literature,” said Richard Stanton, author of The Forgotten Olympic Art Competitions, the only English-language book on the subject.

Coubertin wasn’t merely introducing global athletic competition, he was recreating the competitions held at Olympia, and that meant including the arts. So at the 1912 Stockholm Games, Coubertin introduced the Pentathlon of the Muses, where medals were awarded to sports-inspired art, including painting, sculpture, architecture, and poetry (lyric and epic). And Coubertin actually won the first gold medal in poetry for his poem “Ode to Sport,” submitted under the pseudonyms Georges Hohrod and M. Eschbach:

O Sport, you are Beauty! . . . O Sport, you are Justice! . . . O Sport, you are Happiness! The body trembles in bliss upon hearing your call . . .

A few setbacks killed this potentially great idea, though. The arts competitions suffered from a severe lack of interest from the day’s most celebrated artists, and as a result drew increasingly mediocre submissions. And the ill-conceived idea to require all submitted works be sports-inspired was instantly marred by a fatal flaw: there just weren’t that many serious writers writing about sports. While I recognize the obvious nod to Pindar’s victory odes, this required theme is comically narrow. Who didn’t notice that this criterion excluded 99.9% of current genius-level production? What if the only running event was the marathon? Consider what we’d be missing. We know one thing: Bolt’s Tranströmer-penned tribute wouldn’t be happening.

Another blow to the Olympic arts was new IOC president Avery Brundage and his insistence on “completely pure” competition. This meant only amateur athletes were permitted to compete, which excluded artists supporting themselves by selling their work. Brundage also disliked the idea of an artists profiting from the endorsement of their work that Olympic medals would undoubtedly provide. So after much debate, the artistic Olympic events were killed after the 1948 games and the awarded medals were wiped from the record. (Or maybe it’s a good thing. It wouldn’t take too much effort to engineer a hefty petition to include parental bloggers writing about little league follies in the Games of the XXXI Olympiad. . . .)

Anyway. Now you know how literature singlehandedly saved the Olympics. Hey NBC, maybe serious literature can get a cut of some of those ad dollars?

In my next post I’ll tell you about the many ways the IOC is paying tribute to its literary saviors.

John Tyler Allen is a freelance writer in New York City.

For Further Reading

Peter Armenti, “Pindar, Poetry, and the Olympics,” Library of Congress, 27 July 2012.

NPR Staff Writer, “Honoring the Games, and the Past, with Poetry,” NPR, 27 July 2012.

Tony Perrottet, “Champions of Verse: Poetry’s Relationship with the Olympics,” New York Times, 29 June 2012.

Joseph Stromberg, “When the Olympics Gave out Medals for Art,” Smithsonian, 25 July 2012.