EDITOR'S NOTE, July 2011

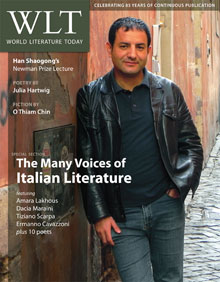

Ma la gloria non vedo. If the glory of ancient Rome and Renaissance Italy had faded for Leopardi by the early nineteenth century, for many the Risorgimento (1815–70) that led to her unification, after Leopardi's death, marked Italy's glorious return. Earlier this spring, Italians around the world marked the 150th anniversary of unification that had culminated, symbolically, on March 17, 1861, with the proclamation of Victor Emmanuel II (who barely spoke Italian) as king. In the week leading up to the anniversary, the University of Oklahoma was fortunate to host the Honorable Fabrizio Nava, consul general of Italy, who gave a talk about the Risorgimento as part of a two-day celebration honoring eminent Italian playwright, novelist, and poet Dacia Maraini, who visited Oklahoma that week. Highlights during Maraini's visit to campus included a gala evening and performances of her play Mary Stuart, animated conversations with students and faculty in informal settings, and the interview with Monica Seger that appears as the marquee feature, in this issue, in our special section devoted to contemporary Italian literature (page 27).

Even as celebrations of the Unità d'Italia echoed up and down the peninsula this spring, certain discordant notes were struck by those who questioned whether unification, in the words of David Gilmour, had truly been "an exemplary case of liberty triumphing over repression." (Gilmour's new survey of "the diversities and centrifugal inclinations in Italian history," The Pursuit of Italy, was published in the UK earlier this spring and is forthcoming in the US in fall 2011.) If at the end of the eighteenth century, according to Gil-mour, Italy remained "a literary idea, an abstract concept, an imaginary homeland or simply a sentimental urge," by the early twenty-first century, many wondered whether the country, the perennial "sick man" of Europe, should be considered a "failure" as a nation, to echo the titles of two recent studies. In the Veneto, one of the last regions to be annexed during unification, a crowd in Vicenza celebrated the national holiday in March by burning Garibaldi in effigy. Politically, economically, and socially, the glories of past golden ages seem muted in the bright glare of corruption scandals, anti-immigrant xenophobia, economic stratification, and constant media babble.

No surprise, then, that the fourteen Italian authors presented in this issue are both "out of step with their own time" yet "uniquely positioned to observe it," as Jamie Richards notes in her essay on Gianni Celati and the Emilian writers (page 48). In a country that sometimes seems "incapable of recognizing and valuing its cultural patrimony," Italy's writers, in the words of Algerian-born novelist Amara Lakhous, should not be viewed as "saviors of the nation" or "modern-day Garibaldis" (page 44). Rather, the authors featured here nurture personal patrimonies, reflecting current realities but, for the most part, only obliquely commenting on them. Emblematic of their stance is the speaker in Maria Luisa Spaziani's "The Glory": "the poet always scatters her words to the wind / – three thousand drones die for one to touch the queen – // this is the heaven to which other names are given" (page 46). In her concluding stanza, Spaziani writes: "the most famed marble can suddenly reveal / flaws more slender than a hair, / then everything cracks, crumbles, and the vain menhirs / melt into wind-swirls, they suck away your name." In Spaziani's Italy, as for Leo-pardi, the glory of ancient arches, columns, and statues is veined with historical—and human—mutability. The authors in this issue reflect more the diversity than the unity of contemporary Italy, sharing a common language even as they scatter their words to the wind.

Editorial note: Dacia Maraini's visit to the University of Oklahoma was made possible by generous support from the following campus sponsors: the College of International Studies; Friends of the College of Arts & Sciences; Department of Modern Languages, Literatures & Linguistics; School of Drama; and the Puterbaugh Foundation, in cooperation with the Italian Cultural Institute of Los Angeles.