The Improbable Reality of Europe's Dark Past

The waves of mass killing that swept across the old Mitteleuropa during the 1930s and ’40s are neither forgotten nor ignored by twenty-first-century writers. Four recent novels illustrate this contemporary coverage and raise the issue of historical reality’s function in fiction.

“Righteous Jews so respect the name of G*d,” Paul Verhaeghen tells us in Omega Minor, his astonishing tour de force of a book about bad faith in the twentieth century, “that they do not dare to . . . throw away even the smallest slip of paper for fear that it might carry the Lord’s name. . . .” Jewish law, and the systematic record keeping of the Germans, have meant that the oddest, cruelest years of European history are exceptionally well documented. An entire postwar literature has grown from the attempts to reconstruct the period from roughly 1930 to 1945 out of the mass of paper evidence.

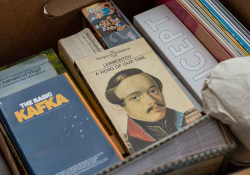

By now, novelists from a third postwar generation are at work on the texts about that dark time. Much of the new writing might be called “reality-fiction”—fiction spun around facts drawn from secondary as well as primary sources. These novels are neither truly documentary nor traditional historical novels, but rather dispersions of a mixture of facts, and reflections on these facts, within an invented matrix. By trawling the packed archives, the piles of eyewitness accounts, and the secondhand analyses, the authors have tried both to capture “what it was really like” and to understand the implications of the past.

Moving between a fictional present and the irreducible facts of the past is an approach in several insightful but not “documented” novels, from Time’s Arrow (Martin Amis) to Everything Is Illuminated (Jonathan Safran Foer) and Beatrice and Virgil (Yann Martel). In The Exception, by Christian Jungersen, a contemporary thriller plot intersects with an overview of current ideas about the persecution of minorities. Jungersen has spun a many-layered narrative around the staff of the (invented) Copenhagen Genocide Centre, a device that allows him ample space for thoughtful comment on ethnic cleansing during World War II.

But perhaps the best recent examples of discursive, historically anchored “dark ages” fiction are four very ambitious books, which all happen to be very large (700–1,000 pages): Omega Minor, by Paul Verhaeghen (2004); Europe Central, by William Vollmann (2005); The Kindly Ones, by Jonathan Littell (2006); andThe Emperor of Lies, by Steve Sem-Sandberg (2009). These books are singled out for literary reasons, but it impossible not to note that all were written by highly educated, cosmopolitan men born within ten years of each other (1958–67).

Omega Minor

Written by Paul Verhaeghen (Belgium), Omega Minor is the most argumentative, the most reckless with time and place, and the most absurd of the four selections, but it is also very enjoyable. As Verhaeghen told an interviewer: “It quickly became, in so many ways, a novel of excess. Because to me, the only way to write about excess is excessively.” The many plotlines unravel and rejoin from time to time in the Berlin of the present and of the 1940s and in the nuclear labs of Los Alamos. The interlocking stories are powered by fantasy and interspersed with speculation on the meaning of violence—whether it is ordered or disordered, sexual, or used as a means to some other end. Auschwitz is the narrative’s still, mad center of annihilation; the bomb its raving, equally crazed counterpart.

The protagonist, like the author, is a cognitive psychologist—curious and nonjudgmental—but in the end unable to cope with his self-imposed task of recording the memories of a Holocaust survivor. The old man’s tale grows into a tortuous saga about a genius of survival— an ex-magician who is either victim or perpetrator (or a bit of both) as the story rambles on through a series of “real” settings: camps, prisons, hideouts, and police stations.

Or, could it be that the enigmatic storyteller is no more than a very well-read plagiarist, whose “life” has been composed as a patchwork of bits and pieces culled from known texts, from novels and accounts written by real participants in history? It seems as “true” as anything that we have been told.

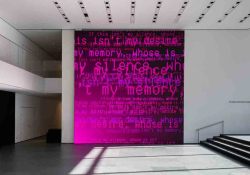

This ambivalence challenges moral judgment, as do the enigmatic women (essentially the same woman—all beautiful, sexy, and intellectually brilliant) who, in different guises, undermine certainty at every turn. The author has said the impetus to write the novel hit him in Berlin, at Bebelplatz, with its poignant book-burning memorial: “I found myself alone on this huge square, except for a strange glow coming from a glass plate in the pavement. Underneath it was a small white underground chamber lined with empty bookshelves. On it was that famous Heine quote: ‘Where they burn books, they will end up burning people.’” The bitterness of it all keeps haunting him, and as the ex-magician in Omega Minor explains: “The Nazis are not killing a people—what they want is to turn back modernity, get rid of rationality and its twin brother uncertainty.” Or, as the narrator-psychologist muses elsewhere in the book: “The struggle is of Text against World. The World wins.”

Europe Central

William Vollmann was born in the United States in 1959, but has traveled widely. In Europe Central, Vollmann fictionalizes people from Germany and the Soviet Union in intertwining novellas. The idea is that the narratives cross and recross each other in a metaphorical telephone exchange that links the two hostile but oddly similar systems, transmitting stories about the bad, the good, and the confused on either side of the geopolitical divide. The main characters are all historical figures, some of them very grand, and their novelistic lives closely follow their documented lives. Many are artists and writers, for instance Käthe Kollwitz (remembered for her moving, precise drawings of people in wartime) and Roman Karmen (a documentary filmmaker and, often, Soviet propagandist). Some, like Hitler and Stalin, are paired off in recurring exchanges; some are given lengthy repeat appearances, notably Shostakovich, his mistress, and his band of alarmed but devoted friends. Vollmann himself is an ever-present background presence, commenting with a sometimes witty, sometimes didactic voice in knowing asides.

Europe Central is both a strange book and a remarkable achievement with its guiding if sometimes clunking core concept, careful chronology, and meticulous apparatus of notes. Vollmann is noted for his violent novels, culminating in a whole series devoted to “comprehending worldwide violence,” but Europe Central makes for less brutal reading than one might expect, given the author and the subject. And curiously, for a writer who has already written a lavishly footnoted study of “violence through the ages” called Moral Calculus, it is relatively short of moral conundrums.

The Kindly Ones

Moral issues, notably arguments for moral relativism, make up a hard core in The Kindly Ones, by Jonathan Littell (U.S./France). It is an absorbing, shocking book, written with a sustained brilliance shading into the grotesque and occasionally into utter weirdness. The cultured, sophisticated narrator-protagonist, Max Aue, is a senior SS officer. He participates, with varying enthusiasm and breaks for reminiscence, illness, fantasies, sex, and foreign travel, in a seemingly endless sequence of violence and atrocity. Famously—for this book became a literary or, to some critics, a pornographic sensation—Aue, who after the collapse of Germany leads a respectable postwar life, concludes plausibly that cruelty is a product of time and place: “I live, I do what can be done, it’s the same for everyone, I am a man like other men, I am a man like you. I tell you, I am just like you."

Littell’s inquiry into the mind of the enemy is sustained by facts about everything, from set pieces of persecution to the minutiae of titles and uniforms (the book’s glossary is long and helpful), and from social chitchat to academic texts on racial biology. Aue’s compulsive discourse veers from ordinary humanity to contemplation of death statistics and philosophical aperçus, and back again. The sequence of events is orderly, despite complicated flashbacks. Because Aue is such an adaptable, smooth operator, it is almost believable that he should turn up wherever his author wants him to be, including every step of the German campaign in Russia. Discrete borrowings from Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate suggest that Littell has a worthy master, although he lacks Grossman’s authoritative clarity and compassion.

Littell, who used to be an aid worker in the dangerous states of the North Caucasus, is an impressive writer. He shares with the other three not only a dedication to data and a preference for mixing real people with invented characters, but also the capacity to make his huge book an engrossing read.

The Emperor of Lies

Steve Sem-Sandberg (Sweden) is an ex-foreign correspondent who has written other works of fiction about twentieth-century tangles of European politics, violence, and suffering, but never at such length. Set in the ghetto in the Polish city of Łódź (1939–44), The Emperor of Lies is a fusion of recorded and imagined reality. The narrative is based on the Łódź Chronicle, a compilation of archival material compiled by ghetto inhabitants; this collection of documents is perhaps only matched by that found hidden in the ruins of the Warsaw ghetto.

Chaim Rumkowski, one of the real-life characters in the book, and arguably its protagonist, is singled out as an emblematic figure: he is the “Emperor of Lies.” Rumkowski was the German-approved Elder of the Jewish Council, whose pride in keeping “his Jews” alive became inextricably contaminated with defeat as, again and again, he gave into his German masters and executed their increasingly insane orders. Fate has lent tragic stature to this energetic and, in many ways, deeply unpleasant but well-meaning man, whose life’s work began in 1939, at the age of sixty-two. By 1944, broken by an impossible task and staring death in the face, he ruminates: “They liquidated the Warsaw ghetto. As I sit here today, there are 78,000 Jews left in the [Łódź] ghetto. And the Russians are advancing. . . . So if I save 78,000 Jews. 60,000. 50,000. I’m not afraid of anything. What will they do to me? I’m an old Jew. Sick.” At one time, the ghetto held over 200,000 people.

It is painful to read the intricate, compassionate evocation of some of the people living in this overcrowded, run-down townscape, more painful still because they are doomed: when the five years of misery had passed, nearly everyone had died, in the ghetto, the death camps, or the final slaughter just ahead of the Russian advance. Unlike the other three “reality-novels,” The Emperor of Lies has a classical focus on place and continuity of time, which heightens its impact even as it limits our grip on what happened outside the ghetto walls. Sem-Sandberg’s engagement with his subject matter lends depth to the narrative—he knows every street corner, and the illusion of reality is enhanced by the inclusions of sayings, verses, and jokes, often in Yiddish, as well as quotes from memorandums, letters, speeches, and diaries.

Reality Novels?

Sem-Sandberg rejects that historical reality has a critical function in his novels. When an interviewer asked him about his works of fiction that are created around real characters in real settings, he said, among other things: “[The historical approach] is simply a methodology, a way of coming to grips with a topic, a tool among many others in the kit. Including documentation may reflect an intention to take the novel to places where it otherwise could not have gone. It helps the reader to relate as closely as possible to the text. But when truly engaged in a story, the reader creates the reality and this is the kind I am after. I’m not trying to say something conclusive about the experiential reality of a previously recorded event. That’s for the historians” (interview with Kaj Scheuler). When asked how the reader would find out what is fact and what is fiction, he replied: “It surely doesn’t matter that much!”

Maybe so. That good stories generate engagement goes without saying; too bad if factual truth comes in a poor second, or even not at all. We do not hesitate to suspend disbelief when told about heroes and monsters, white whales and manipulative computers, Gulliver and K. The imagination can fashion ways to tell truths that cannot be expressed in records of actuality. But writers of reality fiction have complicated things for us: the authenticity might well be illusory, but we can’t help expecting it to be true, especially when backed by a documentary apparatus of proof. At best, as in these four books, the facts are displayed, discussed, and often documented, but only to allow the authors to go beyond the record and let fantasy into the darkest corners of history.

Aberdeenshire, Scotland

Editorial note: To read an excerpt from Sem-Sandberg’s The Emperor of Lies, forthcoming in August 2011, see page 21 in the July 2011 print or digital edition of WLT. For more about the novel, visit the FSG website.