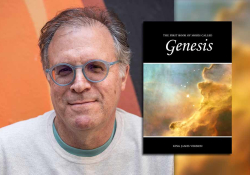

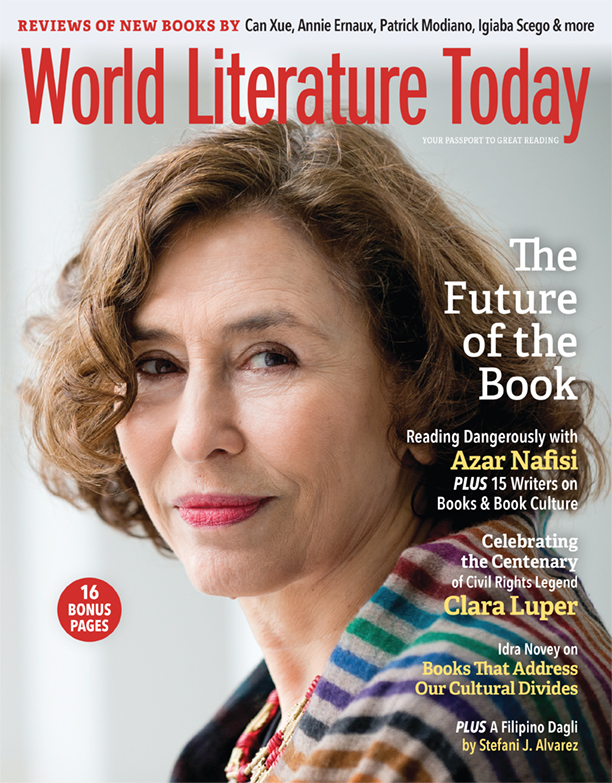

5 Questions for Idra Novey

In Take What You Need, Idra Novey’s third novel, a woman who fled her childhood in the Allegheny Mountains endures an uneasy return when her stepmother, Jean, dies. There in her Rust Belt hometown, Leah is astonished to find Jean’s metal sculptures, what Jean called her Manglements. In this novel of ideas with a propulsive plot, characters take what’s discarded—from a desolate landscape and damaged relationships—and make something meaningful.

Q

Take What You Need is set in the southern Allegheny Mountains, in a town painted in desolation with its boarded-up storefronts and empty, condemned houses, “the hulking emptiness of the mills.” The airport is long-gone, the hospital closed, but political polarization is present. I read the novel as, among other things, a Rust Belt novel. Why did you decide to write a novel set in the Rust Belt?

A

A

One in four people in this country is estranged from a close relative. During the previous administration, I had an intense disagreement with one of my siblings that led to a prolonged, painful estrangement. I couldn’t find any novels that addressed the psychic cost of cutting off communication with a sibling or parent over a political divide. As I have in all my novels, I decided to write the scenes I longed to read.

This novel takes place in the Rust Belt region of western Pennsylvania where parts of my family have lived for over a century, and still live. I’ve come to see the upsides of that rural reality with new eyes, returning now with my children, playing with them in the same creek where I played as a kid. Yet some of the statements on billboards around town, on the signs in people’s yards, are terrifying. This novel became a way to think more deeply about that dissonance, how the ongoing experience of political polarization is impacting me and my children in ways we may not realize for years to come.

Q

What other Rust Belt literature would you recommend?

A

Hanif Abdurraqib is a superb writer from Columbus, Ohio. I loved the poems in his collection The Crown Ain’t Worth Much. One of my favorite novels set in the Rust Belt, During the Reign of the Queen of Persia, by Joan Chase, came out in the 1980s. It’s a quietly radical novel about women’s stifled lives in rural Ohio, the covert ways they seek pleasures denied to them.

Q

Louise Bourgeois and Agnes Martin appear throughout the novel, with Jean quoting them, relying on their wisdom for guidance. How did these two artists come to feature so prominently in the novel?

A

Louise Bourgeois entered the novel after finding a beat-up book of her writing at a flea market. Bourgeois’s insights on sexuality and power, on her father, aligned potently with Jean’s artistic drive. Bourgeois recognized the libidinal forces fueling her sense of defiance.

Agnes Martin’s writing aligned with Jean’s process in other aspects. Martin chose to retreat and work in complete solitude in her later years. While writing Jean’s chapters, I also immersed myself in the writing of Anne Truitt, Celia Paul, Hilma af Klint, and many other women artists. They were all repeatedly dismissed and written off, and yet somehow still found the conviction to keep taking their art seriously. Writing about Jean’s nerve to keep getting on her ladder, stacking her Manglements as high as her room allowed, was a deeply joyful and rewarding process.

Q

In specific moments with both Jean and Leah, we see reflections that could apply broadly to a polarized society. For example, Jean reflects on how isolation takes away the pressure to explain things, to make sense to other people or yourself, and when she and Leah are hurtling down the mountain, arguing about the local men they met on the cliff, Leah imagines them crashing while “arguing over them with such intensity that we lost all sense of our own survival and struck a tree.” Is this what the US is doing?

A

I hoped that larger question would arise for readers, between that scene descending from the cliff and ongoing debates in the United States that are distracting us from focusing on our own survival. Without books that attempt to address our cultural divides, how will we move toward addressing our civic divides? That question accompanied me throughout my many drafts of this novel. I found it quite scary to fully inhabit that argument in the car, to re-create the anguish that Leah and Jean experience at their impasse in the truck, their disgust with each other’s perceptions of what happened on the cliff. Bourgeois said art is a way to be forgiven, and by forgiven, I think what she means is creating art that invites the possibility of mercy, both for others and for ourselves.

Without books that attempt to address our cultural divides, how will we move toward addressing our civic divides?

Q

Who are you particularly excited about reading right now?

A

I love novels that recast fairy tales in subtle, subversive ways. I didn’t intend for this novel to become a fairy tale. That happened after several years of drafts, and after revisiting Helen Oyeyemi’s Gingerbread, Barbara Comyn’s The Juniper Tree, and the radically reconfigured fairy tales of Cristina Rivera Garza, translated from the Spanish by Sarah Booker. Kenji Miyazama’s stories in Once and Forever, translated from the Japanese by John Bester, enchant me anew every time I read them and had a profound influence on Take What You Need.

Idra Novey is the author of three novels and three poetry collections. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, New York magazine, and Paris Review. Also a translator, she teaches fiction at Princeton University.