The Form of the Book

With the introduction of new platforms for reading and engaging with the printed word in recent decades, book lovers might be forced to wonder: Is this a book? The authors mull the protean transformations of books and the ongoing evolution of print culture.

For most people the book still means the printed book. It is familiar as an object and has shown great resilience in the face of competition from other media and attempts at the book’s reinvention in digital form. Comparison with digital content has led to a renewed emphasis on the production quality of printed books, as publishers see the value for readers of the design, paper, and illustrations. The book in digital form has been the subject of much experimentation, but what is striking is that the most commercially successful format is the vanilla ebook, mirroring the structure of the printed book. Catching up fast is the audiobook, a growing area of publishing. For example, in Sweden audiobooks now outsell print books, and in many countries the growth rate of audio is the highest of any sector of the industry. Audio is attracting new audiences and new projects are commissioned directly for this format, some moving beyond the single narrator to offer more theatrical performances. Meanwhile the arrival of AI (artificial intelligence) is spreading ripples through the publishing ecosystem, with the potential for machines to read for us and to write convincing narratives.

If those set on burning books were going to get to work, would they choose an ebook or a CD-ROM? No, they would head to the nearest library or bookshop to source some printed material. Clearing someone’s Kindle or hacking an online library does not make a strong enough statement. The printed book remains the most visible and central form of the book, and during the Covid pandemic bookshelves became the backdrop to many a Zoom call. The printed book is also a reliable technology. The printed text benefits from the economies of scale available from the printing press, and its boundaries are set by the production system.

If those set on burning books were going to get to work, would they choose an ebook or a CD-ROM? No, they would head to the nearest library or bookshop to source some printed material.

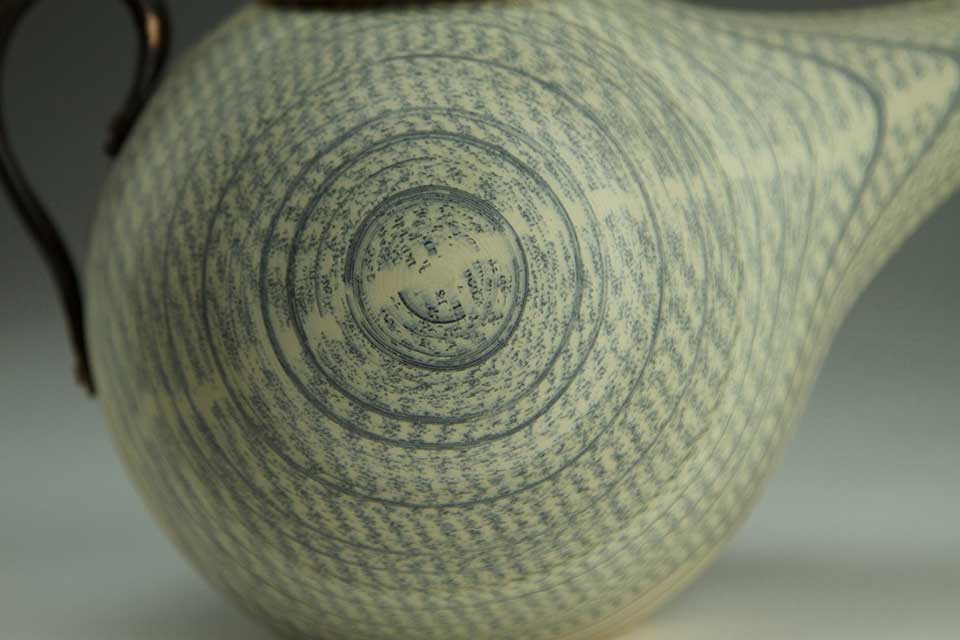

A physical product can be owned and passed round friends and family; in the digital era, it has become a refuge from screens for office workers or parents seeking amusement for their children. Giving a physical book as a present says something both about the recipient but also the giver. The book in print confers status and symbolic capital. Russian oligarchs may never open a book but still want to fill their libraries with leather-bound volumes; chic cafés play vinyl records and use books to decorate the walls. In his 1979 poem “A Martian Sends a Postcard Home,” Craig Raine called print books Caxtons, “mechanical birds with many wings.” Printed books come in many formats and production values, from pocket editions to luxury collector editions. That variety in print is now enhanced by experimentation with digital technology to transform the book.

The Digital Book

Books have been presented on CD-ROM, as apps, and as enhanced ebooks with multimedia. The high costs of such projects, against relatively low sales and low retail prices, have so far proved largely unsustainable in consumer markets. However, in educational and academic markets, digital content and services have replaced many print products. In the 1990s, when the digital book began to be developed commercially, the view was that in this new format, the book could take off in many directions. The use of hyperlinks would enable books to connect to a host of external content, from text and image archives to live video streams. Of course, this was not the book’s future and the internet itself now offers this functionality, and much reference and other content has shifted online. In turn, books retain their promise of permanence and internal consistency, preferring not to send readers off on tangents.

The most successful digital transformation so far has been the vanilla ebook, reproducing the look of the printed page. For enthusiastic consumers of genre fiction, this type of ebook offers great value with low prices on individual titles and subscription services available. Dedicated e-readers are also free from the distractions present when reading on your phone, laptop, or tablet. The ebook offers some extra functionality compared to the printed book—for example search (an index is no longer required) and the ability to adjust the type size—but also possesses disadvantages, such as little sense for the reader of their progression through the text. Many readers of print have a clear map of the book in their head, and can quickly find an earlier passage, looking on the left or right page, with an idea of how far through they were in the book. You cannot yet smell the paper in a digital book, though one day that may yet come.

You cannot yet smell the paper in a digital book, though one day that may yet come.

If nonlinear forms of text could so easily accomplish what the book format accomplishes, such as in the transmission of knowledge and culture, the book as we know it would exist only in museums. The resilience and continued appeal of print books can be explained if we consider books not as an adversary to screens or as a relic of history but as long-form, linear reading complementary to digital reading and browsing. The book is not only a welcome refuge from the work environment of screens, and a detox from our skimming habit, but also a tool that helps to boost our cognitive abilities, such as depth and breadth of vocabulary and sustained attention—valuable by-products of deep reading.

The book is not only a welcome refuge from the work environment of screens, and a detox from our skimming habit, but also a tool that helps to boost our cognitive abilities.

Reading

Reading is of course not only book reading, and it is happening in many different ways—through work, study, and social interactions. We read thousands of words each day—work and home emails, texts, social media posts, news bulletins—often at great speed. We have become experts at skimming for the key points and headlines across reports, articles, and web postings. This type of reading is functional, necessary to obtain information or to communicate for work. As the amount of information available expands at a fast pace, we can only aim to scratch the surface with our own reading. It is probable that AI will undertake more of this kind of work—machines can work across vast amounts of information, reading books, reports, and articles. Already AI can summarize research papers in a few sentences, and the potential is there for personalized summaries of the information relevant to a person’s interests and work.

For so long the audiobook was seen as the poor relation of the printed book, and yet today it is forging ahead on its own terms.

Audiobooks are starting to be narrated by AI; also AI is writing simple news stories and can write formulaic fiction—the program GPT-3 from the company OpenAI can generate a story when given an opening sentence. We asked the newly launched ChatGPT program to summarize the future of the book in a few sentences:

The future of the book is uncertain, as it is impacted by technological developments and changing reading habits. One possibility is that physical books will become less common, as more people choose to read electronically on devices such as tablets and e-readers. At the same time, there may also be a resurgence in the popularity of physical books, as some people prefer the tactile experience of reading a printed book or value the aesthetic of a bookshelf full of books. It is also possible that the book as we know it will evolve, incorporating new technologies such as augmented reality or interactive elements. Ultimately, it is difficult to predict exactly how the book will change in the future, but it is likely that it will continue to be an important part of culture and society.

What is the place of reading and books in the digital landscape? Intriguingly, our quick-fire reading habits on the web open up a clear space for long-form, immersive reading. Reading fiction enables us to enter other worlds and other minds and immerse ourselves in stories fueled by the writer’s imagination. Serious nonfiction asks us to grapple with ideas, events, and stories of interesting lives. Human beings express their thoughts with words: the more words we know, the more familiar we are with how words change their meaning in different contexts (in accordance with the rules of logic), and the more complex thoughts we can express. In short, the depth and breadth of our vocabulary is one of the preconditions for critical and analytical thinking—the more words we know, the larger and more complex becomes the world we can think about.

As far as we know, there is no other activity that trains these skills better than the linear reading of long texts. Assuming that deep, focused thinking remains of value, future discussion will turn to whether—and which—screen media can do this job better than printed books. Current discussions on these issues have not reached a definitive conclusion: for example, a set of meta studies has shown that comprehension of longer, educational texts is at a higher level when reading from print than from screen. In contrast, Haruki Murakami believes that form does not matter when reading fiction:

Once the habit of reading has taken hold—usually when we are very young—it cannot be easily dislodged. . . . As long as one in twenty is like us, I refuse to get overly worried about the future of the novel and the written word. Nor do I see the electronic media as a threat. The form and the medium aren’t all that important, and I don’t care if the words appear on paper or on a screen. (Novelist as a Vocation, 2022).

Audiobooks

For so long the audiobook was seen as the poor relation of the printed book, and yet today it is forging ahead on its own terms, finding new audiences and offering different creative possibilities. The idea of an audiobook as simply based on a printed book further dissolved with audio-first projects—for example, with writers’ rooms creating serialized stories—and the book of the podcast just as there is the book of the film. The fiction podcast has attracted interest from large players such as Netflix and Marvel. There has been considerable investment in audio in recent years, from marketing spend to star narrators being signed up alongside a cadre of polished actors, expert at how to read to best effect. Listening to audio means that the experience is being driven by the skills of the narrator in ways that text-to-speech programs cannot compete. Maggie Gyllenhaal has narrated Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar; Tom Hanks has narrated his own story collection Uncommon Type as well as The Dutch House by Ann Patchett. George Saunders’s Lincoln in the Bardo has a cast of many including Lena Dunham, Miranda July, Julianne Moore, Susan Sarandon, David Sedaris, and Ben Stiller.

As a consequence of technological changes, audio media can be consumed on-demand and there is evidence that new generations of listeners are switching from mass-media radio to more personalized podcasts and audiobooks. Could part of the contemporary boom in audio be because this is not reading books—it is a different activity away from what is seen as a more elitist and cognitively more demanding pursuit? There is an undoubted attraction toward audio from new audiences. If audio is an entry point for new consumers, that is a way of broadening the customer base of publishers to people who do not necessarily think of themselves as book readers. The hope in the industry is that the audience for audio is maturing, attracting not just younger listeners but also some more traditional book readers. Yet listening does not require literacy, neither does it help the listener to become a more fluid reader. From this point of view, replacing print-based or screen-based educational textbooks with audio versions is not advisable.

The Future

There is no question that the book’s role in the dissemination of knowledge and information has diminished. If whole categories of knowledge continue their move on to the internet, what is left for the book? Is it the primary home of critical thinking—through deep, long-form reading? Is it perhaps story?—either fiction or narrative nonfiction such as memoir or biography. Are books now just one of many forms of adaptation of story, part of a transmedia journey? For example, from book to audio, screen, or game; or in the other direction from game to book, from screen to book, from web or social media to streaming to book? Many new works of fiction are readily available on literature and fan fiction websites, such as Wattpad, and successful ones attract a lot of attention and many readers. There are also many different forms of storytelling that the contemporary author can pursue, whether a Netflix series or a podcast.

The opportunities from streaming models for ebooks and audio are clear; so too are the risks for industry and author revenues. Yet publishers run the risk of being left behind if the streaming services come to generate much of their own content. The internet has disrupted not only the supply of content but also the retail channels for books. In some countries physical bookstores are supported by grants for smaller shops and by a system of controlled pricing. For how long will such policies be seen as justifiable? In many markets the shift toward online purchasing is a notable trend (accelerated by the pandemic) and physical bookstores often keep going only by selling a broader range of stock including gifts and stationery. For books, the internet works well if you know what you want, or are happy to be guided by algorithms. However, often the delights of serendipity come from a visit to a physical store, as Mark Forsyth recalls:

I never had any desire to read Ukrainian crime-comedy until 2001. I was promenading around a bookshop in north London and I saw a book called Death and the Penguin. It was out on a table, not the first table when you come in the door (footballers’ autobiographies), but the table a little way back where the good stuff is always hidden. I liked the title—the move from abstract noun to concrete—I liked the cover—a man with a gun sitting in a bath with a huge penguin. . . . There are times when you can’t part with your money quick enough. (The Unknown Unknown)

How do we answer the question as to whether the book still matters? By reminding ourselves of the value of books in terms of the pleasure they give and their ability to stimulate thinking through deep reading. To the surprise of many the book is still hanging on in there and is experiencing revitalizing effects such as from BookTok, which continues to take the book world by storm and to give prominence to works from publishers’ backlists such as the retellings of Greek myths by Madeline Miller. We must preach the value of whole books and long-form reading. Nonfiction offers sustained arguments and considered thought, while fiction takes us to imaginary worlds and tells many of the lasting stories that find their way into radio, TV, and film.

The challenges of the modern world leave us searching for answers to the world’s problems and new ways of thinking. Books remain an invaluable tool to help us develop our analytical, abstract, and strategic thinking. This may not always be the case—other tools may appear to replace this aspect of books—but in the meantime let us celebrate the power of books and the joy they bring to many.

Oxford, UK / Ljubljana, Slovenia