Kubbat Ḥamuḍ Shalgham: Turnip and Swiss Chard Chowder, Iraqi Style

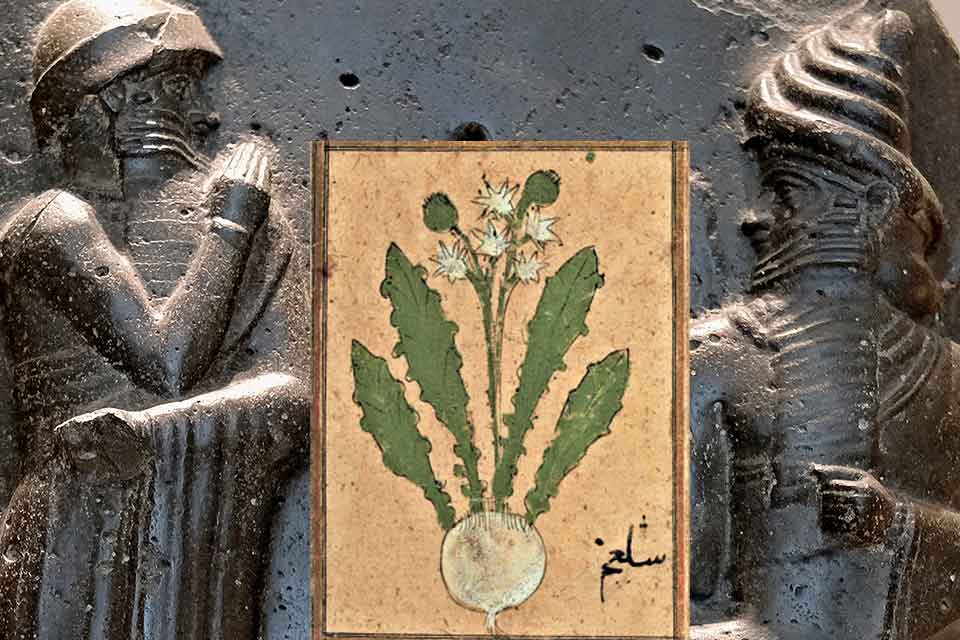

An ancient Babylonian recipe for cooking turnips survived in one of the three cuneiform tablets dating from around 1700 BC.

An ancient Babylonian recipe for cooking turnips survived in one of the three cuneiform tablets dating from around 1700 BC.

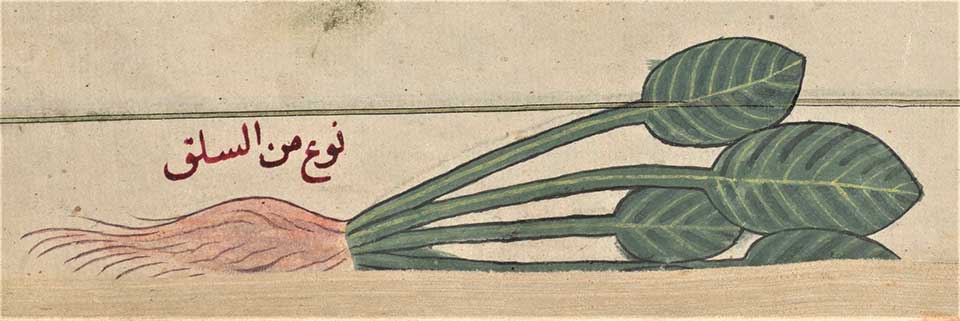

THIS IS A SUBSTANTIAL DISH of a creamy vegetable soup with meat-filled rice dumplings, which can be served as a main meal. The name is a combination of kubba (the filled dumplings), ḥāmuḍ (sour)—on account of the lemon juice used—and shalgham (turnips). It nourishes and satisfies with its harmonious flavors, exciting textures, and a welcoming aroma that says this is home. Admittedly, it is not easy getting people all excited about the humble turnip, let alone the prehistorically giant chard leaf, but I do hope that my enthusiasm toward them will prove to be contagious, because they are really worth trying—quietly tasty and a good-for-you kind of food. And they have been around in Iraq from time immemorial, even etymologically. In the ancient Akkadian, language of the Babylonians and Assyrians, turnip was called laptu, from which the Arabic lift was derived (the present-day Iraqi dialectal shalgham for turnip was derived from the medieval Persian loan word, sh/saljam). Regarding the chard, its Arabic name, silq, was derived from the Akkadian silqu, which designated the beetroot and the chard.

What is really fascinating is that an ancient Babylonian recipe for cooking turnips survived in one of the three cuneiform tablets dating from around 1700 bc. They were discovered in the early twentieth century on the site of ancient Babylon (see Jean Bottéro, The Oldest Cuisine in the World, 2004). The best preserved of these tablets contains twenty-five recipes of stews written in a telegraphic style. One of them uses cultivated turnips with no meat, in addition to water, onion, arugula, cilantro, and Persian shallots (Allium stipitatum). Toward the end of cooking, the dish is flavored, enriched, and thickened with the addition of bulb leeks (Allium porrum) mashed with garlic, and bread crumbs mixed with blood (later prohibited by both Judaism and Islam). The Babylonian stew dishes most probably reflected the kind of daily fare offered to the elite household members for their nourishment and sustenance—as we still do today. Evidently the turnips were deemed important enough to be included in this high-cuisine collection of recipes.

As we move further in history, we learn more about these two vegetables. In the medical opinion of the medieval physicians and botanists, for instance, who followed the tenets of the Galenic theory of the four humors, prevalent at the time, both chard and turnip were valued as an effective cure for cold-related ailments, on account of their hot and humid properties. They were also held in high regard for increasing blood and semen, and were said to work as aphrodisiacs.

In the medieval kitchens, they were used in the most delicious of ways, based on the two medieval cookbooks that survived from Baghdad. Chard, for instance, as described in the thirteenth-century Kitāb al-Ṭabīkh (Cookbook), by al-Baghdadi, was boiled and mixed with drained yogurt and garlic, and served as a side dish. Turnips were cooked in white sauce, as described in the tenth-century Kitāb al-Ṭabīkh, by Ibn Sayyār al-Warrāq. The dish, this time over, was richly thickened with crushed chickpeas, ground almonds, milk, and rice. Meatballs made with lean meat pounded into paste were thrown into the simmering pot. This is not quite dissimilar, I dare say, to how we continued to cook the turnips.

In Iraq today, Kubbat ḥāmuḍ shalgham is a winter treat because both turnips and chard are available in that season only; and as in medieval times, we also swear by their power to soothe cold symptoms. Interestingly, the traditional Jewish Iraqi version of it replaces the turnips with another ancient root vegetable, the beet. There is no satisfactory reason for why this is so. However, it is my suspicion that this was a culinary tradition that the Babylonian Jews of Baghdad preserved from their continual presence in the region from ancient times. In the previously mentioned Babylonian stews, there is indeed a meat stew cooked with beets, the first documented borscht dish, which might have been later adopted by the Jews.

In the pre-food-processor times, making this elaborate soup was indeed a labor of love, what with all the pounding and grinding of rice and meat for the dumplings. Nowadays, it is only a matter of minutes to make it, and with some planning, the dish can be enjoyed fuss-free, such as preparing the stuffing the day before. Optionally, you may skip the dumplings; cook the soup only and perhaps drop in some meatballs, like the medieval Baghdadi cooks used to do.

Making the kubba filling

1½ pounds lean ground meat

3 tablespoons oil

2 medium onions, finely chopped

1½ teaspoons salt

½ teaspoon each of black pepper and allspice, with a bit of chili pepper, to taste

¼ cup each of chopped parsley, slivered and toasted almonds, and currants or raisins

Put meat and oil with ¼ cup water in a large skillet and let cook on medium-high heat; stir occasionally, breaking down meat lumps, until liquid is almost gone, about 10 minutes. Stir in the rest of the ingredients, and continue cooking and occasionally stirring on medium heat until onion looks translucent and all moisture evaporates, about 10 minutes. Set it aside to cool.

Making the kubba balls

(about 16, size of a mandarin each)

12 ounces lean beef, ground

2 cups (12 ounces) rice flour

1 teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon black pepper

about 4 tablespoons water

Mix ground beef, rice flour, salt, and pepper. In three batches process the mix in a food processor, adding water through the spout, a tablespoon for each batch, or a bit more if mixture looks dry. A ball of dough should start forming and revolving within 2 to 3 minutes. Repeat until all is done. The final dough will be pinkish in hue, pliable, and of medium consistency.

Make the kubba balls by taking a piece of the dough, the size of a golf ball, flatten it into a thin concave disc—you need to make it as thin as you possibly can to avoid ending up with tough kubba. Put about 1 heaping tablespoon of the filling in the middle, gather the ends to close it, and roll it into a ball between the palms. Remember to handle the dough with slightly moistened fingers. If, while shaping, the dough tears at a place, take a small piece of the dough, flatten it between your fingers, slightly wet the torn area, and patch it. Put the finished pieces on a tray, in one layer, until the soup is ready.

Making the soup

1 medium onion, chopped

2 tablespoons oil

3 medium turnips (about 1 pound), peeled and cut into 1-inch cubes

4 to 5 big Swiss chard leaves with the stalks (about 3 cups chopped)

1 teaspoon crushed coriander seeds

½ teaspoon turmeric

½ cup rice soaked in water for 30 minutes and pulsed with the water in a food processor

1½ teaspoons salt

½ teaspoon black pepper

¼ cup lemon juice (or to taste), plus ½ teaspoon sugar

In a large pot, sauté the onion in oil until it starts to soften. Fold in turnips and chard, about 5 minutes. Fold in the rest of the ingredients, and pour in hot water or broth to cover them by about 5 inches. Mix well, and stir in the pulsed rice. Bring the pot to a boil, and then reduce heat to medium-low and simmer, covered, until turnip is tender and soup starts to thicken slightly, about 20 minutes. While simmering, stir the pot several times.

Drop in the prepared balls of kubba, stir the pot carefully, and let it boil gently for 20 minutes until the dumplings cook, and serve.