Circling around Remembrance: A Conversation with Dorthe Nors

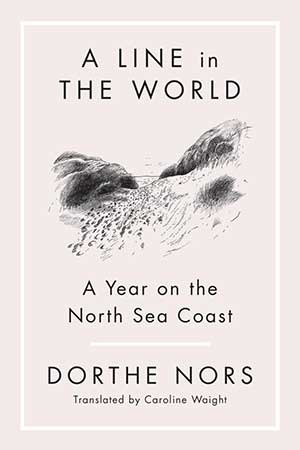

Celebrated Danish writer Dorthe Nors’s first nonfiction book, A Line in the World, translated by Caroline Waight, is a stunning work that documents a year she spent traveling along the North Sea coast of Denmark, moving from Skagen to the Wadden Sea. “Wandering Houses,” from Nors’s collection of fourteen essays, a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award, was published in the September 2022 issue of World Literature Today. Nors is the author of the story collections Wild Swims and Karate Chop, two novellas, and four novels, including Mirror, Shoulder, Signal, a finalist for the Man Booker International Prize. In her most recent book, her spare and stunning prose depicts the harsh Jutland Peninsula with immediacy, as she moves between the past and the present to record a nuanced and layered place. This work is as much about the external world as it is an exploration of inner weather and personal memory, and the result is an expansive and intimate archive of movement and belonging.

Kathryn Savage: In your essay “The Tracks around Bulbjerg,” you write, “The landscape is an archive of memory.” What did you mean by this line?

Dorthe Nors: I wrote A Line in the World in one year. One of the first things I noticed when I traveled in this landscape, which I’ve known my entire life, was that episodic memory was stored in the places I went. You see, that’s how we work: we remember things when we reenter places we used to live in or travel through. Visit your childhood school, for instance, and I’m certain that an episodic memory that you’ve not been in touch with for ages will emerge from “the archive.” The famous Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen, who traveled a lot, said: “To travel is to live.” I changed that phrase a bit in A Line in the World: “To travel is to remember.”

Dorthe Nors: I wrote A Line in the World in one year. One of the first things I noticed when I traveled in this landscape, which I’ve known my entire life, was that episodic memory was stored in the places I went. You see, that’s how we work: we remember things when we reenter places we used to live in or travel through. Visit your childhood school, for instance, and I’m certain that an episodic memory that you’ve not been in touch with for ages will emerge from “the archive.” The famous Danish writer Hans Christian Andersen, who traveled a lot, said: “To travel is to live.” I changed that phrase a bit in A Line in the World: “To travel is to remember.”

Savage: You write both fiction and nonfiction. Would you describe the relationship between form and content in your own work?

Nors: I want to write in all kinds of forms. I couldn’t imagine spending my entire life as a writer who only writes novels, for instance. I love language. I love the things it can pick up on, describe, dig into. I treat my language as if it was an instrument; a cellist didn’t become good at playing the cello without rehearsing every day and challenging themselves. The same with language for me. I want my instrument to really develop and grow, as a linguistic art, so I change forms. And while it’s true that A Line in the World is composed of fourteen essays, I prefer to call them chapters since the book turned out to feel like one continuous essay to me.

Savage: I once heard you describe writing a short story like standing on a stage and singing without stopping, You must be there! Do you think the essay form asks something different from the writer?

Nors: I think that there will be elements of the intensity and the “in situ” presence of the short story in both the novel and the essay, as writing forms. The difference between novels and short stories is of course the length and the way intensity varies in the novel. A Line in the World has both novel and short-story qualities, but the difficulty here was that facts and nonfictive information—about landscape, places, local history—had to be embedded in the prose. That was quite a challenge. Essays tend to be didactic and lean toward an urge to educate the reader, and I don’t like didactic information, preaching, etc., being mixed up in my literature. I worked hard to figure out how to solve that problem. You could say that A Line in the World is a fusion of three forms—novel, short story, and essay—without completely being any of them.

Savage: Across prose forms, how do you balance the ideas that drive your work with the scenes and people themselves?

Nors: That’s a very difficult question; I hardly know if it can be answered. The theme, the intensity, the way it’s staged, comes from the “machine room” inside the writer, and we hardly know how that works ourselves. And we probably shouldn’t know either!

Savage: Your collection of essays is a journey story. You write terrifically about paths and walking. In what ways are paths like memory, and in what ways might paths be like writing, too?

Nors: As the Norwegian neuropsychologist Ylva Østby says in “The Tracks around Bulbjerg,” “When a memory pathway arises in the brain, it can be similar to the way a path forms over time: two neurons keep stimulating one another, and gradually a stronger connection develops between them.” I wanted to see how that worked in the landscape, because going from one place to the other in a landscape makes paths, and we form these paths together with wildlife and other people who move around in the same place. I would say that most of this book in some way circles around remembrance and memory. In many ways it is a memoir. Following paths is the same as remembering, and the landscape has a memory of itself. Places remember. The question is: do we?

Following paths is the same as remembering, and the landscape has a memory of itself. Places remember. The question is: do we?

Savage: “The Secret Place” is about an important childhood home and the public health harms done to the local community—your family and others—by nearby Cheminova, a factory that produces chemicals. “But when the lights are on at Cheminova,” you write, “I don’t think about poison. When darkness falls, the Secret Place on the salt meadows is transformed into a cave, and those of us who sleep in it into foxes.” I felt grief and deep tenderness while reading your powerful essay.

Nors: I grew up as a summer cottage neighbor to a very visible chemical factory placed in the middle of a vast landscape; the factory lives side by side with cherished memories of my grandmother, the fjords, flying kites, and going fishing. I know the water levels are rising, but I also know that in that particular place they have been rising and falling throughout my life. Living next to a force of nature is to live with the consequences of being small and minuscule. Apart from lamenting the stupidity of mankind, this chapter also contemplates the ways that time moves. It’s like that song by George Benson: everything must change / nothing stays the same.

Living next to a force of nature is to live with the consequences of being small and minuscule.

Savage: Returning to your fiction, I’ve always been deeply interested in your short story “Flight,” from Karate Chop, both for what it includes and leaves off the page. I know that you’re a fan of Flannery O’Connor. You’re both expert at noir, a gothic sensibility, and, equally, poking fun at it. When I think of your work beside O’Connor’s I recall her Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, where O’Connor praises characters who have an “inner coherence, if not always a coherence to their social framework. Their fictional qualities lean away from typical social patterns, toward mystery and the unexpected. It is this kind of realism that I want to consider.” What is it that you want to consider in your realism?

Savage: Returning to your fiction, I’ve always been deeply interested in your short story “Flight,” from Karate Chop, both for what it includes and leaves off the page. I know that you’re a fan of Flannery O’Connor. You’re both expert at noir, a gothic sensibility, and, equally, poking fun at it. When I think of your work beside O’Connor’s I recall her Mystery and Manners: Occasional Prose, where O’Connor praises characters who have an “inner coherence, if not always a coherence to their social framework. Their fictional qualities lean away from typical social patterns, toward mystery and the unexpected. It is this kind of realism that I want to consider.” What is it that you want to consider in your realism?

Nors: Oh that’s a big (big!) question. I must stress that I didn’t grow up reading Flannery O’Connor. When I had the international breakthrough with my short-story collection Karate Chop in 2014, I gave a lot of interviews in the US and was frequently asked which American writers I loved. I wrote my thesis on Swedish literature, I’m an expert on Nordic literature, and had not read enough American literature back then. I had, however, recently read Flannery O’Connor’s novel The Violent Bear It Away and loved it. O’Connor’s writing emerged from a different background, geography, and religious atmosphere than my writing, but we probably both have a good sense of the movements of characters—what people hide, what they don’t tell, what drives them. When I think of O’Connor, I relate to her exploration of the gothic; being a Scandi writer, that comes with the territory.

I studied a lot of eminent Swedish writers at university. Later, I discovered the movie director Ingmar Bergman. I sometimes describe my writing as being more connected to Ingmar Bergman—who, by the way, was an excellent writer. I’m not sure if you can tell from my writing that I feel connected to him, but I do. There’s something in his approach to material—the inability to close one’s eyes, the need to address and explore deep existential phenomena and structures—that I truly like. But there’s a bit more humor and satire on my half of the court.

When I think of O’Connor, I relate to her exploration of the gothic; being a Scandi writer, that comes with the territory.

Savage: Will you describe your relationship with translations of your work? Do you read the translations?

Nors: I used to be a translator (from Swedish and Norwegian to Danish) myself, so I know how the translation process works. I participate in the beginning of the English translation for different reasons. Number one: it must be ready even before the Danish version is published. Number two: my books get translated into several languages, but English is the only one I participate in. Doing it like that, we can always tell translators from other countries to have a look at the English translation if they’re in doubt about something.

On top of that, writing in Danish means writing “beneath the lines” at times, and it’s good to make sure that this doesn’t go amiss in the process. On top of that, there’s a dialect, Jutlandic, in A Line in the World. The manuscript goes back and forth between me and the translator, in this case the amazing Caroline Waight. We discuss things in the margin, and then she brings the English version home in the very best of ways.

I think some translators find it horrible to have a writer lurking over their work process like that. But I work in English myself (articles, essays, interviews), and sitting in on the translation in the beginning means that I’m very familiar with the English version of my book before it’s published. Caroline has worked with brilliance and patience on A Line in the World. I think she did such a great job on this book.

Savage: A Line in the World is your first nonfiction book. Will you write another?

Nors: Who knows! I’m quite anarchistic when it comes to form. I’m probably going to pop up here and there with formally different books. Right now, I’m writing a novel, and that’s very fun.

January 2023