After the Transitions

We can clearly see today from a cultural perspective that the symbolic year 1989 ushered in a specific kind of prosperity for the literature of this part of the world (see WLT, “After the Wall Fell,” Nov. 2014). Interestingly, the traumatological prosperity of Polish literature—the “young” poetry and prose—flourished in Germany, which after the fall of the Berlin Wall and reunification contributed with an open heart and mind to the rapidly rising European careers of such writers as Olga Tokarczuk or Andrzej Stasiuk. A relatively fluent transfer into target languages and the critics’ significant interest—including the likes of Marcel Reich-Ranicki—led to judgments about the ways in which a specific kind of central European experience could, through its literature, contribute to enrich the spiritual heritage of the old continent, or at least of its postmodern and wealthy part that, through a happy alignment of political conditions, found itself on the right side of the Iron Curtain.

Broadly defined, central European literature turned out to be a kind of “accursed share,” to use the title of Georges Bataille’s 1949 book, that “European literature”—also broadly defined—internalized as its own, hitherto invisible imago. The historical experience of a war waged by two totalitarian regimes—plowing through Europe while contributing to the collapse of Enlightenment myths—found its reward as the “black sun” of the twentieth century began to shine with full brilliance. Writers, many of whom had suffered an unwanted and forced quarantine in the camp of communist states, began to enter the canon of European literature. The majority of them has already fallen on the trash heap of literary history for having missed the historical reset that is etched in our minds through photographs of meetings between Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev or cross-stitched portraits of John Paul II, who called on the Holy Spirit to renew his homeland during his pilgrimage to Poland.

The effectiveness and dynamism of the historical process are measured not by individual human beings but by galaxies of interstate interests or blocs of states sharing the same system like the one that happened in 1989. In fact, 1989 turned out to be a postmodern “Orwellian year” for Poland or, more precisely, its beginning. Literature was very much aware of it because it was not swept up in the fever that accompanied the social strengthening of the Solidarity movement. In my opinion, far fewer than the ten million Solidarność members were real democrats and committed citizens. In a country of forty million people, four out of five people were not mentally ready for change. It is precisely to this mute and politically indifferent majority that the most important texts of Polish-language writers who debuted after 1989 were devoted. In fact, to this day, one can hear disgruntled longings for a great contemporary novel that would explain to us who we really were as a society and what changes we have undergone in the last four decades of Polish freedom—a freedom brutally tamed today by small autocrats like Jarosław Kaczyński, a devotee of the new “Smolensk religion,” whose cult launched like a supernova after the plane carrying his brother crashed in 2010.

To this day, one can hear disgruntled longings for a great contemporary novel that would explain to us who we really were as a society and what changes we have undergone in the last four decades of Polish freedom.

One thing is certain: four decades of democracy have not fundamentally altered our Polish tendency to mythologize circumstantial, most often casual, historical facts. Above all, the readers’ and literary critics’ pining for a “Great Novel” should be at home in this collective tendency to undergo hypnosis and in the persistent longing for the cult of personality that we inherited from communism. After all, the consistently high approval ratings of 30 percent for the ruling party and for Jarosław Kaczyński has its roots in communism. Simply put, in an exemplary democracy, no one will live our life for us. One must take individual responsibility. Meanwhile, a significant proportion of my compatriots would rather have someone else live for them. Even if that someone is a moral gnome.

The future of Polish literature is not the novel but the essay.

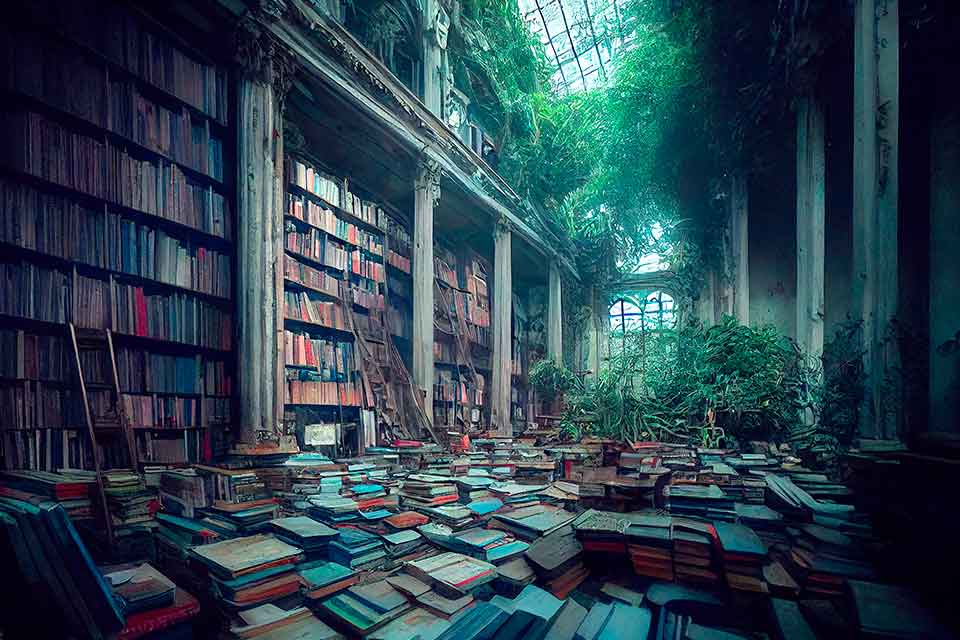

Therefore, the future of Polish literature is not the novel but the essay. It is a defective, discontinuous, highly mysterious literary genre, in which there is room for the idioms of one’s own language and a somewhat narcissistic eloquence that is as personal as it is borrowed from the great library of the world. Contemporary essays written in Polish seem to me to be a daring attempt to measure up to the traumatology of our historical experience and to the accursed resentment toward the cultures of strong, major, and dominant languages. (I do not mean English or any other geopolitical area.) As a society, we find ourselves somewhat in the position of a “Bloomian” subject who does not cope well with a “strong” poet. Rather, it is about the lack of certain experiences or the episodic encounter with them, as for example with the Enlightenment. If people as enlightened as the Germans could feel its spectacular collapse happening in the crematoria of Auschwitz, for us this Shoah was the obvious companion of the doom whose source should be sought in the premonition of catastrophe as the immanent structure of being that is characteristic of the East. Poland—which in the age of Romanticism was the “Messiah of Europe” and whose people had an eternal, divine predestination—experienced the Enlightenment but for a brief moment. Its European historical framework troubles the Polish republic only fragmentarily. Simply said, in this country on the Vistula River, rationalism did not find an easy home. The Holy Spirit fared much better, although today it barely survives under the weight of a rapidly secularizing society. We became orphans not so much after the “death of God,” although Friedrich Nietzsche was translated here very quickly, enjoyed the most progressive writers of the early twentieth century’s respect, and influenced their writing. We became orphans from our representations of this death, unable to see beyond the Second Coming. We miss the contemporary novel as much as we miss a paternalistic God who will return to reestablish the rules of time, place, and action in the drama of our postmodern life that today is not much different from the postmodern drowsiness and boredom in Michel Houellebecq’s France or from Peter Handke’s tired “Don Juans.”

The essay, on the other hand, still seems to me to be a worthwhile option for the future of literature. It is more than a perch for genre literatures that organize the global book market and unfortunately shape the tastes of a shrinking literary audience. What is worse, the essay is simply an escape forward, a kind of prediction of various scenarios for one’s own life that is fulfilled as much in the library as in intuitions that allow us to dive again into our individual consciousness—be it a specific historical moment like the year 1989, for example—into depths whose keys are still in the hands of the great and probably unsurpassable writers of modernism, such as Samuel Beckett, Emil Cioran, or Ingeborg Bachmann.

Not wanting to pay mere lip service, I try to write essays besides poetry, fully aware that they can be treated as an escape from a specific narrative imagination that should legitimize a prose writer of flesh and blood. Nevertheless, the knowledge of idioms seems to me more important than story and narrative. That is why I had serious reservations about Olga Tokarczuk’s Nobel speech devoted to the “tender narrator,” to whom male and female writers owe a sick and still traumatological modernity. It seems to me that the world we made does not deserve such a narrator if he still has the courage to face the truth of his pandemonium.

In an essay written some time ago, I tried to reconstruct who I was and how I felt in 1989. I was twelve years old at the time, everything seemed possible, and history had returned before Francis Fukuyama predicted its end. With John Ashbery, I could say, “I thought things were going well, but I was wrong.”

* * *

He begins to detect within himself a tendency to swagger, to utter bad words in a falsetto that is slowly deepening.

Walking along a typical city street, he is twelve years old. The heat is building although it is only the end of May. Tar drips from the heating pipes that cross the canal, and they might flood the garden plots. He looks at a stream of fables and waterfront legends. He was told that the U-boat keels precluded a river invasion of the east. And laughter emanates from the toothless men who gathered yesterday for the last commemoration of the end of a war almost invisible in everyday life. At gatherings, he recites versified nonsense while glancing at Russian tits clad in lycra. Sweaty armpits raise arms holding a carnation in a Roman greeting. Two totalitarianisms fade at once into the future; the solidarity of the third begins. After leaving school, he rushes to pick up stickers with a mollifying logo. The goal is to acquire the efficiency of a volunteer who proclaims the possibility of freedom for all. Freedom’s dawn. Freedom spreading the germ of democracy. A large group of enthusiasts has already gathered in front of the polytechnic. Pioneers and leaders lick posters because the glue in the buckets has run out. Quasi-bankrupt, interested florists distribute anthuriums right and left, the wino sphinx rights himself on crutches and looks questioningly at the chalice. Fighters bring model Spitfire airplanes and try to draw him in. With a Russian Zenith pen he draws peacock eyespots on their wings, then on a Katana denim jacket that has come to get his stamped certificate, which he has received before the end of the semester, once in a lifetime, because the platinum blonde youth-torturing math vampire has camouflaged herself into maternity leave. Things are falling into place. He stops slouching. He considers switching from his old bike to a BMX. On the square, long saddles, plastic pouches, bike frames covered with new terrycloth, metalheads coming out of the Spodek hall praise German trash. “It’s not enough for the Creator to fuck things up, the Protector has to do it too.” He begins to detect within himself a tendency to swagger, to utter bad words in a falsetto that is slowly deepening. He smokes to be hoarse, to please a group, because nowadays everyone goes in small groups to meet in one large group at the arena. He is already sitting in it like a clam, he is the trusted man, telling how it will be, when it will be over and how “ours” will be at the top. He sees more and more people coming from the direction of the water tower, wet and sweating, asking, mingling with the clams, their faces twitching from the minisneers of the trusted man, “legs, legs, hundreds of legs, stomp, stomp, tup, tup, tup” can be heard from the Fiat Mirafiori belonging to the one who achieves freedom earlier, thanks to export crystals he did not have to wait in line for his vitamin shot, he could care less, every day and ostentatiously he turns the key in the ignition switch that purrs professionally, no fuss no muss, no stick needed to crank the engine. That winter he had looked for a suitable stick in the cellar, and behind the furniture he had found, blackened by coal, the pole of a labor banner. His father was freezing his buns off until the engine started coughing to the delight of the owner of the Granada, which had been hauled on a cargo ship for dinars and halvah, gold and foxes. Now he sees them both, hissing “keep talking” to the trusted man, despised by wives who see clear weather ahead, the juicer can kiss my ass, enter the sturdy Moulinex, a normal robot for people. “Are there other questions? No questions.” Everyone comes in and out of the elevator church that spits out spikes, flesh thrown from the dark lands under your feet, inches funnily to the exit, descends the stairs proudly like an alien matrix, a liquid womb emerges in the center, straight onto the representative sidewalk that leads to the parody of civic celebrations of citizenship, femininity is born, the smoke behind the porter’s watchtower moves into the gardens’ paths, clasps fall from fabric, a ghost in shreds hangs on a rope, raising your head does not improve the sight. His father says, “Come, there’s no point.” May turns into June, June into July, oh surprise, because instead of rapid change, a triathlon of gray mice is training here, locals and money changers become the shareholders and missionaries of extra new illusions, emigrants start taking away boilers from the boiler room, Poldek vouchers are used on the black market at car fairs, the last spies serve loyally and are characters in films for which he is waiting as impatiently as for the last summer camp of his youth. A holiday lake district, an island with a monastery on the water, which the Pope in his popemobile liked, overnight in a shaky aquarium, but with foosball in a glass hallway. A bunch of country bumpkins. A lot of grown-up boys, erections on the brain, a daily silent postprandial massage with a blanket. And at night, like clockwork, on bunk beds, the momentary tears of someone screwed by a pedophile with privileges in the militia commons. Before the nocturnal silence, games of hide-and-seek and roasted sausages on a stick by the fire. Happiness in misfortune. He learns that it is his turn on Wednesday, the middle of camp week. He spills the beans to the supervisor, who runs as if possessed to the pier with the paddleboats, but all are tied with chain and padlock, so she screams toward the kayak on which the instructor has been practicing his balance since dawn. A smoothie and the soul of the party by the fire, when the boys are already asleep, he feeds the staff delusions till they puke. After a moment of phone calls, the bitch comes out of the telephone booth and drags the boys’ guardian in the missionary position, on his knees, he cries and screams that “he didn’t want to, it was not like that.” And suddenly camp is terminated and he gets a commendation for his vigilance. He will put it in a fancy green certificate holder closed by a rubber band and a button. He comes home on a bus like a flying carpet, tells his parents; his father, ashen, mentions the possibility of murder, although nothing happened to him, his turn had not come. The others did not come out of the woods until August. Part choice, part trauma. In jail, apparently, there were no ifs or buts, the murder was described in the underground newspaper. He is afraid that this September he won’t have a satchel, that they’ll have to take a military surplus backpack or a German shoulder bag with a zipper to hide sandwiches, and without side pockets with insignia patches! Surplus it will be. Perfect for decals and patches! King Diamond clashes somewhat with Israel and four-leaf clovers, but camo goes with everything. A tripwire is permanently set at the school’s entrance, but he already knows how to kick ass and already has his first razor blade. The whole evening after the gala he assembles and takes apart his father’s razor, cleans out the dried foam and facial hair, his mother says that this beard has been sitting there since “before he was really born,” because the last time his father shaved was after meeting him in the delivery room, the sight gave him a firm resolve to improve that is awaiting his early retirement, when there won’t be anything to drink to or anyone to drink with, because most engineers can’t handle the world, one will hang himself by standing on a potato crate from his own cellar, another will become the boss of an illegal coal-smuggling railroad operation, and yet another will live quietly after a stroke. What else doesn’t he know yet? What else awaits? The razor handle’s knob unlocks the pocket, and the razor blade falls softly into it. He looks sideways through the razor blade at the deficient landscapes, lilac-pink plastic tiles, hallway, room, “concrete, concrete, block, block, elevator, house” in their daily murmurs. He is starting to fall in step with the Crisis Brigade although it doesn’t exist. Polishsilver. Quicksilver in Motion. Under the kiosk a string is waiting. He stands at the edge of it, and for the last time he sees a girl whom he knows and desires. The betas are all packed up and ready to move out of the zone. His buddies have prepared a farewell fundraiser. An adapter with “disintegration.”

Translation from the Polish