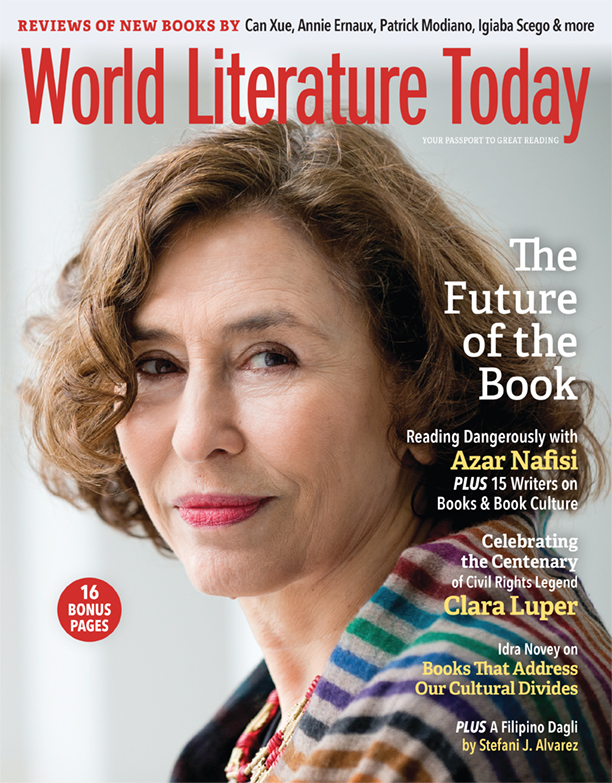

Books in Perpetual Becoming: A Conversation with Serge Chamchinov

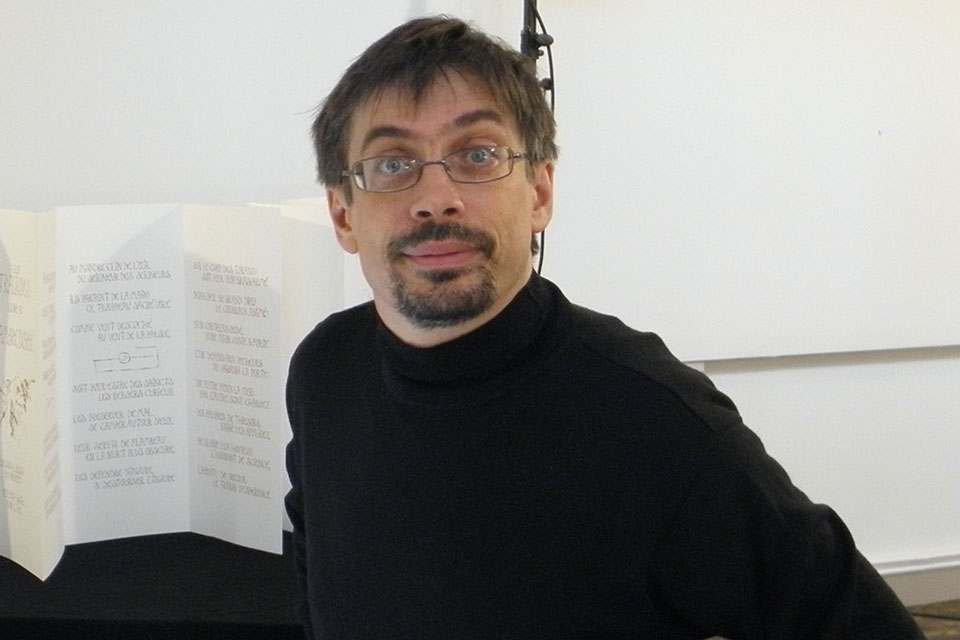

Serge Chamchinov is a man of many languages and a scientist, visual artist, writer, and book binder. He creates first, then self-promotes his books through book reviews, exhibitions, and poetry festivals. Through graphic reading and analytical typography, he develops recurring themes in a palimpsest of books, notebook series, or installations, each becoming part of an ephemeral structure, the “nomadic museum of the artist’s book.”

Serge Chamchinov is a man of many languages and a scientist, visual artist, writer, and book binder. He creates first, then self-promotes his books through book reviews, exhibitions, and poetry festivals. Through graphic reading and analytical typography, he develops recurring themes in a palimpsest of books, notebook series, or installations, each becoming part of an ephemeral structure, the “nomadic museum of the artist’s book.”

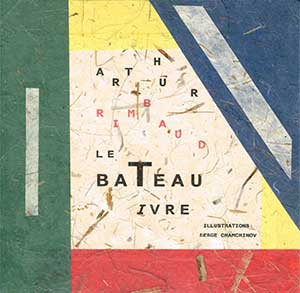

Alice-Catherine Carls: Your work seems to use a method called “organic,” as a plant that grows from a seed and develops little by little, especially one that is cultivated, to obtain not a fragile lily but a powerful and durable oak. The organic method in literature also starts from a seed. This is what I see in your work on Rimbaud. Starting from a poem, you develop books, translations, graphic works involving several authors, translators, and artists. The “drunken boat” seed considered as chaff by many of the poet’s contemporaries survives and is doing well, thanks to your work of many years.

The livre pauvre is a variant of the organic method that is more specific in scope since it is usually limited to one book with multiple authors. It too is for me one of the ways to shape the book of the future. Both the organic book and the livre pauvre have a genetic file and are unique, of course; their gathering of multiple voices is above all unifying, therefore of great magnitude.

Serge Chamchinov: For me, the term “organic” is mainly related to chemistry, which has a special place in my biography. I first studied chemistry at the university. The observation over long periods of time of experiments on the picturesque transformation of organic substances in flasks stimulated my imagination and gave me a taste for serial work. Even after I left this field to create my books, I kept this scientific spirit and interest in long-term experience. What fascinates me is the study of the smallest details and the development of a subject.

Serge Chamchinov: For me, the term “organic” is mainly related to chemistry, which has a special place in my biography. I first studied chemistry at the university. The observation over long periods of time of experiments on the picturesque transformation of organic substances in flasks stimulated my imagination and gave me a taste for serial work. Even after I left this field to create my books, I kept this scientific spirit and interest in long-term experience. What fascinates me is the study of the smallest details and the development of a subject.

Such an approach corresponds to my artistic projects like the one on Arthur Rimbaud’s “The Drunken Boat.” On the other hand, the concept of “later genesis,” which I often elaborate in my books, opens the way for the book to be “in perpetual becoming.” In my creations, I want to touch and even direct the future of the work. The goal is to program certain aspects of the artist’s book so that they continue after the work is finished. Knowing, for example, how the support’s color and structure will change over time, we can anticipate the visual effect in relation to the image installed on this support.

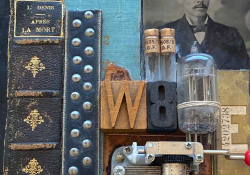

Carls: Your books are out of the ordinary by their size, their appearance, the quality of their paper; from the first glance, the aesthetic of the fonts and the illustrations takes precedence. Taking them in hand is already a “transport” to this elsewhere that any reading promises. What method do you use to produce these books?

Chamchinov: The first thing that happened to me in my youth was the discovery of reading as a process that not only follows the writing or the topic at hand but also opens the self. Very often I read books as the invention of something else than what was written. My thoughts were quite far away during such readings, and I discovered a world of the “distant interior,” in the words of Henri Michaux. It is the traces of those journeys that I fix in my artist’s books. While reading, I would take a pencil and make drawings, and I called it a “graphic reading” method. I developed it in my first artist’s book entitled Clef graphique pour le Château de K. [Kafka], which featured sixty-six drawings. A little later, I came across an article by Hermann Hesse, namely his “Essay on Reading” published in 1920 in the Vienna newspaper Neues Wiener Tagblatt. This article confirmed my thought that there is a form of reading where the reader can become (in his imagination) a creator of his own work while he reads.

Subsequently, during my university studies, I returned several times to this thesis, which is confirmed, for example, by Roland Barthes in Pour une théorie de la lecture, or also in Paul Ricœur’s notion of “configuration,” applied to the question of identity, in Soi-même comme un autre. “Graphic reading” revealed itself for me as the form of a new creation from something read (i.e., a “configuring act” or a process of producing a visual graphic narrative parallel to the work read). Such a narrative was without illustrative value, because it was autonomous from what was written in a book; I was taking a theme, a subject, a notion, or even a single word and developing it in my own way. This method has guided me ever since in making an artist’s book based on a literary work. Recently, when studying the materials concerning Stéphane Mallarmé and his unrealized 1899 project Un coup de dés . . . with Odilon Redon, I learned that he hated the word “illustration” by calling it “defective,” which I completely agree with as far as the artist’s book is concerned.

The “graphic reading” method, which characterizes a conception of the work generated, is not the only one that I exploit. My work follows the principle of individualization, that is, each book, and even each copy, is individual. The question of multiplying copies is not mine. Even we can say that I least like the “copies” in the idea of publishing. The word “multiple” has another meaning for me than producing and sharing copies. So, all the books I do are differentiated. Even if there are a certain number of copies, they are never exactly the same. Let’s clarify this idea with an example. In issue 11 (June 2017) of the magazine Ligature, which I co-founded in 2012 with Anne Arc, an artist, poet, and medievalist, the colophon announces the printing of twenty-six copies, but in reality, it is not the print run. For each new copy contained a different chapter of Franz Kafka’s The Castle, so there is no repetition from one copy to another, and all twenty-six notebooks of a single issue of the magazine make up the entire text of Kafka, while each copy remains unique in its content.

As for the drawings, they constitute the main content. Each time, I try to go toward a succession of gestures; that is why there are variations (series of images) and why my books appear thanks to this visual variation. This may explain the fact that I often return to the same subject, even several years later, and I start doing it again and drawing another book. Since 1989, for example, I have returned at least twelve times to The Castle. Each time it was another presentation, another book shape and format, another conception. If in 1989 it was a “graphic reading” whose drawings appeared in the book without any text, then, in 1990 and 1993, it was a study on the “gallery books” with the installation of legends for drawings that can be removed from the book. There have also been series of drawings, the suites, their variations (of techniques), accompanied by different forms of legends—for example, handwritten, printed on transparent sheets, in German, French, etc. Then, in 2005 and 2009, I experimented with the tiny form of presentation, and the books were bearing small keys on the binding, for example, thus becoming tactile objects. From 2013 to 2016, I pursued the integrality of text and drawings about The Castle, their installation resulting in their separation into twenty-six notebooks to have possibilities of “modulations” and constructions. In 2016 this creation was called Counter-Current Modulations and proposed an almost infinite number of constructivist models for its installation in space.

I feel that the book in general and the artist’s book in particular are threatened.

Carls: Thinking about the works you have created over the past thirty years, how do you see the progression of your conceptions, in terms of long-term books, livres pauvres, and artist’s books?

Chamchinov: Over time, the concepts that I try to develop in my books gradually become thoughts. When I return to the same subject, it is to approach it at another level, one that is sometimes richer and broader in its construction and presentation. On the other hand, with new subjects I also want to arrive at other conceptions; examples include my 2022 Vertical Score: Invention of The New Scoring System, a “book-score” that is made in three registers: verbal, visual, and musical. Or my 2010 “metabook” that contains other artist’s book(s), such as MMXI Meta-Book, the “encircled book” that includes an additional document embedded and sealed in the cover up to a specific date (e.g., 46? or the 2016 Plume ad Partes).

Sometimes I announce projects that are organized under the sign of utopia and move toward the creation of the ideal book (“book-citadel”), sometimes realized in a very large format, or of book-installation or book-performance. This is happening because I feel that the book in general and the artist’s book in particular are threatened. The scope of the spatial presentation of the book fascinates me more and more over time, because I see here the passage from discreet work, the research work carried out in the studio (which is the origin of all artistic creation) to the outside world, to which the book-opus can and wants to be proclaimed and to impose itself. Thus, the exhibition of a single book in a given space (unique is concrete) is the ideal culmination of this type of utopian project, as was the case for the performance of Agrippa d’Aubigné: Les Tragiques during an exhibition in Niort in 2016.

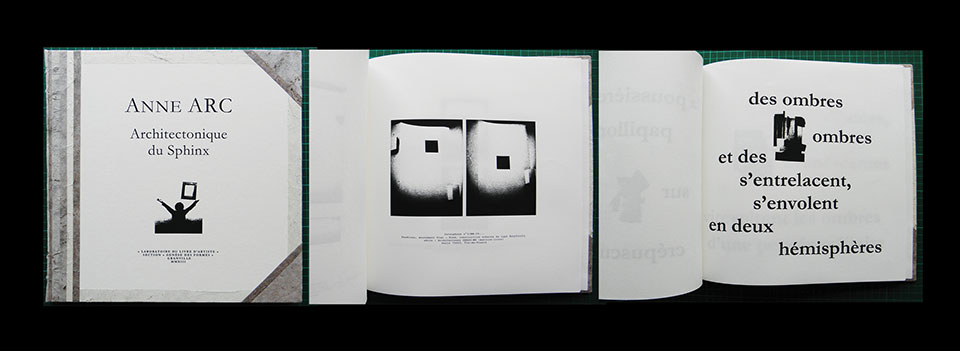

On the other hand, these “utopian” projects are moving toward the creation of the collective book. To achieve it, we created ten years ago an artistic group called “Sphinx Blanc.” At the very beginning there was Anne Arc’s book, Architectonics of the Sphinx (2013), from which comes the first text of our manifesto. Its current version was written in 2020, signed by twenty artists and poets, and translated to date into six languages. Here we invented a formula, “A Book is in Perpetual Becoming,” because it responds not only to our present circumstances and work but also to the demand of the century; it looks into the future. This book allows several contemporary artists, poets, and philosophers to participate in the project either by expressing themselves or by commenting (graphically or verbally) on specific points of this manifesto, aiming to be the vector of the future. The interest of this book is therefore that it enters into the progression of time itself by reflecting the seed text.

It was a bit in the same direction that the project “The Twenty-First Century on The Drunken Boat” was launched in 2012. It is quite optimistic in spirit. Today it brings together more than fifty artists, poets, and translators, and it is gradually developing from one year to the next. Not only do we observe the creation of new works, but we exhibit them; to date, there have been eleven exhibitions in all, among which at the Rimbaud Museum in Charleville, the Gutenberg Museum in Mainz, the Maison Losseau in Mons, and the Champollion Museum in Figeac. At the root of this project lies the idea that it is intended not only to create a unique collection of a single literary work but also to scan today’s international book art scene and present the individual work of today’s book artists.

Carls: Such large projects woven on your “reading” canvas, which underpins all your works, are adorned with work from other authors and artists, allowing the original themes and multiple variations of your collaborators to intersect and intertwine. This you call building the book of the future. Could any reader adopt a similar approach, after learning from you?

Chamchinov: For books made in collaboration, I find that there are several ways of working. One consists of an agreement between the participants who undertake to share the tasks of creating parts of a new work according to their common interest in a chosen theme.

There is always one person who takes on creative responsibilities to get to the finish line. This was the case, for example, of the book Tora (2009), whose theme of doors in nature pushed the German artist Andreas Hegewald and me to make the book together by working on a roll shape (with two unique copies), where each of us drew his part (series of paintings), and where the construction mechanism was then invented by Andreas. Another book, Binary Opposition (2011), was composed by three artists: Max Marek, Anne Arc, and me, with each of us working independently from one another and creating drawings and texts that I installed in the book; the design was finalized at the Biblioparnassus-III Biennial by Max Marek in front of the public.

The project of the group Sphinx Blanc on Wassily Kandinsky was built around Kandinsky’s unpublished poem related to his book Klänge, realized in 1913, which was his only artist’s book. We discovered the existence of an almost unknown manuscript and made several research trips to Munich to find and consult this manuscript. Then we invented a very avant-garde design that transformed the text into a multilingual visual score in which Kandinsky is imagined as the graphic narrator. We can see that this work is launched toward the future, toward the public, who will have the ability to detect all the finesse of the content of this book and all its associative links.

Indeed, I think that the artist’s book goes toward the future in the sense that its functioning is not yet well formulated or studied. Thus, one must free oneself from the stereotypically parasitic notions that come from other fields and not characterize the essence of the artist’s book as an autonomous art genre.

The reader (receiver) who is on the other side of my books has for me the role of a friend, an unknown participant.

In this context, the book of the future that seems to have been conceived as such is Never Again: White/Black (2011). This book uses Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” and his translations into French by Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé. Each page represents a typographic and/or graphico-sculptural object. Composed in two volumes, Never Again could have served as a “manual” for typographers, editors, researchers, linguists, philosophers, and any converted reader. The book offers on each page a new conception of the layout and explains all the details of the design and artistic work so that the receiver can decipher the hidden coded information. It seems to me, however, that I addressed not only a curious reader but one who likes to think and is able to crank up his brain.

In addition, this book opens the possibility of showing the functioning of an artist’s book in the time to come. Its aesthetic is not only a pleasure for the eyes but a teaching work. In fact, the reader (receiver) who is on the other side of my books has for me the role of a friend, an unknown participant. And that is true for all my books. When the reader discovers my book, he will build his own model, and, paraphrasing Vincent van Gogh, I propose to him a game of intrigue according to which “the forms must here do the thing.”

February 2023

Translation from the French

The great-grandson of Armenian painter Arutyun Chamchinyan, Serge Chamchinov settled in France in 1999 and earned a PhD in 2006. A major figure in the development of the artist’s book since 1989, he is the editor in chief of the journal Ligature, which is entirely devoted to artist’s books. He has published more than three hundred titles, initiated numerous artistic projects, and co-founded the international group White Sphinx with Anne Arc, a French plastic artist, poet, translator, and museum exhibition director. Their Jazz / Dada exhibition in Aix-en-Provence runs through May 20, 2023.