The Diversification of Irish Literature: White Truth or White Lie?

While Ireland’s increasingly multicultural population has finally led to a greater representation of diversity in Irish fiction, this essay reveals how much ground is left to be covered and questions why this might be.

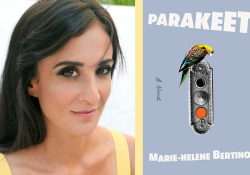

First Flight

In the early 2000s, Irish American author and academic Oona Frawley completed her debut novel, Flight. A beautiful and subtle tale of family, memory, and belonging, the book was sent out to a range of Irish publishers, and Frawley waited eagerly for a response.

Pretty swiftly, each one got back to her with a simple and resounding “no.” Some, after a degree of probing, provided slightly more detailed feedback. It was the protagonist, you see, that was the problem—the Zimbabwean woman who cares for the novel’s elderly Dublin couple as they enter the first stages of Alzheimer’s. The Irish public just wasn’t “ready” for a book with a black female lead—it wasn’t the publishers’ fault! Other editors were more open-minded, suggesting Frawley simply change Sandrine’s ethnicity to Polish (and by implication, white), a shift that would apparently render her a far more digestible main character.

Frawley declined.

Almost a decade later, along came Tramp Press, a small, newly formed Dublin press that, in adding its voice to the publishing cacophony, was willing to add Frawley’s—and indeed Sandrine’s—voice, too. Flight received glowing reviews from the Irish Times and Guardian and was shortlisted for the Irish Book Awards. It appeared Ireland was finally “ready” for diversity in literature.

What happens to the literature of the homeland of a diasporic people when other people’s diasporas converge?

This happy ending might be seen to belie a more widespread development in Irish society; that is, an increased tolerance toward its immigrant populations, and a resultant readiness for more diverse fiction. Certainly, since Flight’s inception, this immigrant population had dramatically grown, the influx of new arrivals posing the question, as asked most pointedly by Irish sociologist Steve Garner: “What happens when other people’s diasporas converge on the homeland of a diasporic people?” But there is another question that still remains to be asked (and answered): “What happens to the literature of the homeland of a diasporic people when other people’s diasporas converge?” Did Flight’s arrival really mark a shift in the Irish publishing scene? Or, even now, does the historical whiteness of the Irish canon prevail?

Coming and Going

Famously, Ireland is a nation of emigrants. Over the course of the last two centuries approximately ten million people have left the Emerald Isle, with an estimated seventy million people worldwide boasting Irish descent. However, as a result of the economic boom that began in the late 1990s and ultimately became the infamous “Celtic Tiger,” Ireland experienced an unprecedented influx of people, leading to net immigration as of 1996 that continued to rise for ten years. A country previously synonymous with emigration was suddenly transformed into a point of arrival.

During this time, many remained optimistic that Ireland’s troubled, exilic past could now inspire a sense of affinity or empathic solidarity with its migrant communities. However, it became apparent pretty quickly that this was not to be the case. Instead, there seemed to be a marked sense of resentment among Irish-born natives who perceived these new residents as having it easier than the Irish did when they once emigrated themselves. Meanwhile, others argued that Ireland’s experience of emigration has never been fully resolved, and that the resultant collective trauma leads to refugees being viewed as degraded images of the Irish self and ill-treated accordingly. Such hostility ultimately manifested itself in a 2004 referendum decreeing that the constitutional right to Irish citizenship should remain limited to those in possession of Irish blood ties, rather than those “merely” born on her shores.

The Citizenship Referendum takes place about halfway through Flight, forcing the characters into uncomfortable but necessary discussions about undocumented workers; about “birth tourism”; about the “new Irish.” The characters also acknowledge the irony of Ireland’s hostility toward these newcomers, given their own diasporic tradition. The elderly couple Claire and Tom, for instance, spent much of their own lives living and working abroad, and now that they are back in Ireland among family they struggle to feel at home: “My house,” Claire says, “is full of strangers from all over the world.” Similarly, later in the novel when someone in the street calls Sandrine “a fucking asylum-seeking nigger,” she hurries back to the house “aware that it was indeed her refuge, for Claire and Tom . . . were all, in a way, foreigners too.”

Ireland’s Others

This analogy between the emigrant Irish and their fellow diasporic groups has featured throughout Irish literature. In 1987 Roddy Doyle’s novel The Commitments delivered the line: “The Irish are the niggers of Europe” (though this was later altered to “the blacks of Europe” for the film and stage adaptations). Many others have suggested a parallel between the Irish and African American experiences of persecution (often via famine ship / slave ship comparisons), while some have posited overlaps with the Jewish people, deeming the Irish another “Chosen People,” dispersed from their “Promised Land” (interestingly, in Northern Ireland it is in fact the Loyalists who fly Israeli flags and the Republicans who fly Palestinian flags, mapping their own conflict onto that of the Middle East).

However, Elizabeth Cullingford’s book Ireland’s Others warns against this process of “analogy,” given how it can prove both ethically problematic and, in many cases, simply factually incorrect:

Analogies, then, are slippery things: one man’s sympathetic identification is another woman’s “cannibalistic” appropriation, and the construction of aesthetic parallels that elide historical differences or asymmetries of power may appear racist or falsely totalizing.

Certainly the above comparisons not only conveniently overlook the countless factors that render each situation—each people—unique, they also ignore Ireland’s chequered past (and present) in terms of racism and anti-Semitism.

Indeed, by 2005, Doyle himself admitted that his character’s analogous pronouncement—tongue in cheek though it may have been—was no longer factually correct. For, since the publication of The Commitments, there were now “thousands of Africans living in Ireland and, if I was writing that book today, I wouldn't use that line. It wouldn’t actually occur to me because Ireland has become one of the wealthiest countries in Europe and the line would make no sense.” What Doyle began to write instead was a series of short stories for Metro Éireann, Ireland’s only multicultural newspaper, in which he imagined what immigrant life in Ireland might actually be like. Characters of various creeds and colors appeared, not as some kind of analogy for the Irish themselves, but simply as individuals facing the realities of life as an outsider.

Doyle also imagined stories from the insider’s perspective, such as in “Guess Who’s Coming for the Dinner?” where Dubliner Larry Linnane gets a shock one evening after his daughters bring a “black fella” into the family home, unannounced. The tension between Larry’s inherent racism and his innate Irish joviality and hospitality is in part symbolic of his countrymen generally, Doyle’s signature humor gesturing toward some more probing observations. In general, the stories were hailed a success and went on to be collected in 2007 under the title The Deportees. Since then they have spawned theatrical adaptations and New Yorker features alike.

After the Crash

But just when it was going so well, it all came crashing down. Literally. Or at least, economically. As it happened, in the face of Ireland’s crippling credit crunch, immigration flows didn’t stop, but they certainly slowed, while emigration picked up at a new, furious pace. Inevitably, this impacted Ireland’s relationship with its newer arrivals as well as with their visibility in Irish literature. Stalwarts like Sebastian Barry and John Banville redominated the best-seller lists with backward-looking tales of white families and loss, while novels particularly concerned with insularity—such as Anne Enright’s The Gathering or Emma Donoghue’s Room—felt especially pertinent for the nation’s inward-looking climate.

As mentioned, it took until 2013 for Oona Frawley’s Flight to finally be published; for the nation to be “ready” for such an outward-looking text. Then the following year Pilar Villar-Argaiz’s Literary Visions of Multicultural Ireland was released. The arrival of such a volume—the first of its kind—was undoubtedly a significant one, hailing the beginnings of a long-overdue cultural conversation. And yet Argaiz herself still bemoaned the comparative lack of representations of ethnic “others” in contemporary Irish fiction, introducing the entire volume with an explicit plea for more.

Small Progress, Small Presses

Thankfully, in the last few years, a handful of such representations have begun to emerge. Kevin Curran’s Beatsploitation (2013) tells the story of an aspiring rock band with troubled African teenager Kembo at its core. Róisín O’Donnell’s short-story collection Wild Quiet (2016) traces a series of complex immigration narratives both from and to Ireland, thus challenging readers to consider what exactly is meant by “Irish,” “foreign,” or “other.” So, for example, in the story “When Time Stretches,” Alex feels a sense of homecoming as he leaves Ireland behind to visit Indonesia, where he spent his formative years. In “Under the Jasmine Tree,” Ciaran was born to a Spanish mother but was adopted and raised by Irish parents, thus blurring his sense of connection, while in “How to Be a Billionaire,” when the “local” boys shout at Kingsley and his brother to “go back to africa,” they reply simply: “we’re not from africa! we’re from the navan road.”

It still remains for mainstream publishers to fully embrace multicultural Ireland; to trust that their readers are at last “ready” to experience viewpoints that are not their own.

And yet, despite the promise of these new voices (both Curran and O’Donnell were featured in a 2015 anthology of emerging authors entitled Young Irelanders), it is worth noting that both books were published by small, independent presses—New Island Books and Liberties Press, respectively—just as Flight was brought to life by Tramp Press. So it still remains for mainstream publishers to fully embrace multicultural Ireland; to trust that their readers are at last “ready” to experience viewpoints that are not their own. And it is up to us, the next generation of Irish writers, to capture these viewpoints in ways that are as fresh, as exciting—and as unproblematic—as they deserve, finally, to be.

University of Birmingham