The Art of Telling the Truth: Chinese Female Stand-up Comedians

The emergence of “girl power” literally saved the show in Chinese stand-up comedy, while at the same time forming a concerted feminist voice. In this essay—punch lines included—Ping Zhu explains how women comedians in China not only saved the show but stole it.

The female stand-up comedian Yang Li has acquired the nickname “Rock & Roast Black Widow” since she joked about Scarlett Johansson’s character in The Avengers in Rock & Roast Season 3 (S3), a Chinese stand-up comedy competition series that is overwhelmingly popular among the young generation. Commenting on the lopsided male-female ratio in many industries, Yang taunted that the 2012 superhero film has only one female character: Black Widow. She asked the audience: “Black Widow’s superpower is that she has been genetically modified so that she ages much slower than others. How can this superpower possibly save the world? . . . Why does everyone fantasize about women always being young, beautiful, and sexy? . . . Why can’t the heroine be a sixty-year-old woman?” Yang’s gags made the audience roar with laughter.

This is the second year Yang Li participated in the Rock & Roast stand-up comedy competition. She did not make it to the final in the past season, but in 2020 she returned with more girl power and delivered several hilarious punch lines that appear like feminist manifestos. One of her most controversial jokes is on the mystery of men: “You look so ordinary yet feel so confident.” This line went viral on the Chinese media overnight, inciting a few indignant responses from male celebrities. The twist of this joke, however, is precisely that the statement looks so ordinary—if it is said by a man to a woman—yet feels so offensive when it is said by a woman to a group of men.

Stand-up comedy is the art of offense. In many cases, it is the truth in a joke that offends.

Stand-up comedy is the art of offense. In many cases, it is the truth in a joke that offends. Under the auspices of humor, Yang Li persistently shows the prevalence of sexism in the contemporary world by telling the truth on the stage. She openly mocked men: “You are the protagonists of the world, always standing in its center. Every word you say is particularly important and true, showing the future direction for the world.” Yang studied fashion design in college, so in another performance she presented her own misandrist interpretation of fashion: “The supermodels all have skeletal bodies . . . the very existence of their bodies expresses an attitude: the disdain for men. The more men like a certain part of their bodies, the less they want to grow that part. Fashion is such an attitude.”

Yang Li is just one of the prominent female stand-up comedians who competed on the Rock & Roast S3 stage in 2020. Last summer, three seats among the top ten finalists were claimed by women. This new gender ratio on the Rock and Roast stage is surprising, especially when you compare it with the gender ratio in China’s twenty-five-member Politburo, which only has one female member, and the Politburo’s Standing Committee, which has never had a female member. Like the Politburo, the laughter business in China was traditionally dominated by men. Many old-school Chinese comedians, like the crosstalk performers, still refuse to take in female disciples. The mainstream Chinese audience only expects women in show business to look beautiful and sexy, not to be witty and tell jokes. No one predicted that a cohort of young female comedians, all in their twenties, would completely steal the limelight in Rock & Roast S3. Not all of the female comedians are as aggressive as Yang Li on the stage, but they too have created hilarious jokes that deeply resonate with the experiences, feelings, desires, and language of the young audience.

The mainstream Chinese audience only expects women in show business to look beautiful and sexy, not to be witty and tell jokes.

Launched in 2017, Rock & Roast was inspired by the American TV show Comedy Central Roast. The 2015 roast of Justin Bieber was soon translated into Chinese and became a hot video on Chinese social media. In the ensuing years, a form of “youth comedy” emerged in China and quickly gained a large audience among young Chinese, especially those born in the 1980s and 1990s. Compared with traditional Chinese comedy, “youth comedy” features free self-expression, genuine youth experience, as well as nonmainstream language and humor. This newly imported genre of comedy has attracted the attention of big investors and quickly developed its own culture of stardom.

The Chinese Communist Party has a long tradition of moderating and regulating laughter for political ends.

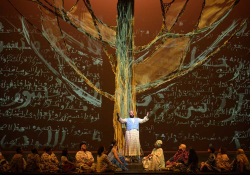

However, being a stand-up comedian in contemporary China is not an easy task. As I wrote in the introduction of Maoist Laughter (2019), the Chinese Communist Party has a long tradition of moderating and regulating laughter for political ends. Laughter is regarded as an important ideological weapon, in the words of Chairman Mao, “to unite and educate people, while attacking and annihilating enemies.” The current Chinese government has inherited this tradition with heavy-handed censorship to sterilize laughter: the comedians cannot talk about sex, drugs, violence, politics, religion, or any sensitive social issues; they cannot mention political leaders or swear on the stage. Being a Chinese comedian, therefore, literally requires one to dance in shackles. Even the established Chinese American comedian Joe Wong has been scratching his head since he left the United States to start his stand-up comedy career in China. The Chinese youth comedy series are oftentimes short-lived, and some of the youth comedians have been suspended. Rock & Roast was also facing a crisis in 2020. The production team desperately needed new faces and new content to attract an audience and reassure investors.

Being a Chinese comedian literally requires one to dance in shackles.

The emergence of “girl power” on the Rock & Roast S3 stage literally saved the show. From their unique gender perspective, these female comedians have not only talked about such gender-specific topics as different social expectations for men and women, cosmetics, plastic surgery, dating, marriage, and women’s friendship but also created penetrating jokes about the generation gap, urban-rural differences, work stress, and the inner world of young Chinese.

Li Xueqin, a graduate from Peking University and a Douyin influencer (the Chinese version of TikTok), has been called the “Genius Girl” since she made her debut on the Rock & Roast S3 stage. Many applaud Li’s tongue-in-cheek humor and provocative punch lines but love her more for telling the real-life stories of ordinary Chinese people. Once Li joked about a conversation with her mother: when she complained about her high-pressure job in the city and proposed to go back home to farm the land, her mother told her their family had no land; when she proposed to farm for the others in her hometown, her mother told her that was no different from working in a company. Li concluded that the reality of contemporary Chinese youth was that they had “no money, no land, no way out, only a ruthless mother.” The joke reveals the grim truth facing millions of young drifters in China: uprooted by the process of globalization, they can no longer make a living by farming like their parents but cannot find their position in the big cities either.

Li used to live in Beijing. In China, the young people who sojourn in Beijing to pursue their dreams are called Beipiao (Beijing drifters). Oftentimes, however, their dreams are crushed by Beijing’s high living expenses and strict household registration requirements. In one of her most electrifying performances, Li compared her relationship with Beijing to that between her and Kris Wu, a Chinese Canadian superstar that Li allegedly likes: “People asked me: ‘Don’t you feel sorry for leaving Beijing?’ They made it sound like I once had Beijing. In the eyes of Beijing, I’m not even a spare tire. I fought for it, saved money for it, and gave my youth to it. When I left, I said goodbye to it. Yet Beijing said: ‘Excuse me, who are you?’” To the young Chinese who have experienced hardship and discrimination in the megacity, those lines would evoke laughter and tears at the same time—this is the response of the deprivileged youth vis-à-vis an overwhelmingly absurd reality. Li’s concluding punch line presses people to think about another easily overlooked truth: “Why do you have to pursue your dream in Beijing? Is your dream holding the Summer Olympic Games?”

Among the female comedians who competed on the Rock & Roast S3 stage, Zhao Xiaohui has a full-time job with a Chinese automobile manufacturer in Guangzhou. Her stage nickname is thus “A Flower in the Workshop.” Zhao is notable for her refreshing and natural style, as all her gags come from her real and raw experiences, such as “the 101 ways of dying” in the hazardous working environment in the factory, and the identical work clothes that prevent the workers from getting to know each other. In her last impromptu performance on the stage, Zhao insisted that she was merely telling the truth instead of performing: “I was just complaining about life, and they told me that this is stand-up comedy. I didn’t know the threshold of stand-up comedy is so low.”

By telling the truth under the auspices of humor, those young female stand-up comedians have formed a concerted feminist voice to challenge China’s mainstream discourse that is still filled with misogynism and indifference to minorities and marginalized people. In refuting the cult of beauty that has haunted female performers, Yang Li joked that her ordinary look worked perfectly for a female comedian: “My look is the just the right degree so that my talent wouldn’t be overlooked by others.” Li Xueqin called her fellow female comedians out: “We should use our humor and wisdom to let men know that every one of us is a beauty!” Zhao Xiaohui, by contrast, declared that she was “a good-looking woman with a nice body and a humorous character.” However, she soon warned the male audience, probably both for herself and on behalf of her female comrades: “Stop sending me weird messages,” she said with a smile, “because you don’t deserve me.”

University of Oklahoma