Bringing a Moldovan Writer’s World of the Absurd to English Readers

A Conversation with Ross Ufberg

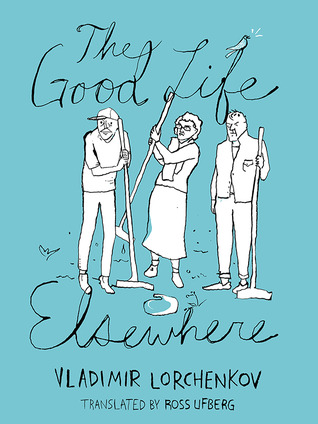

Today is the release date for The Good Life Elsewhere, Vladimir Lorchenkov’s scathing satire from Moldova. Born and currently living in Moldova, Lorchenkov is a laureate of Russia’s 2003 Debut Prize and the 2008 Russian Prize. For ten years, he was the crime section editor of a Moldovan newspaper.

The Good Life Elsewhere follows the tragicomic efforts of the citizens of a Moldovan village to immigrate to Italy—their version of heaven—against the backdrop of Moldova’s ever-strengthening ties to the EU, Russia’s still-dominating shadow, and Italy’s xenophobia.

In this interview, translator Ross Ufberg talks about translating this novel as well as broader issues of translation.

Michelle Johnson: You are the president of New Vessel Press, which publishes books in translation. Could you tell us about this new publishing venture?

Ross Ufberg: New Vessel Press is an attempt, by cofounder Michael Wise and myself, to bring deserving literature from around the world to English-language readers. Literature in translation sometimes gets a bad rap, maybe because so often what’s translated is very difficult, obscure literature—not always a joy to read. When Isaac Bashevis Singer gave his Nobel Prize speech, he said, “The storyteller and poet of our time, as in any other time, must be an entertainer of the spirit in the full sense of the word, not just a preacher of social or political ideals. There is no paradise for bored readers and no excuse for tedious literature that does not intrigue the reader, uplift him, give him the joy and the escape that true art always grants.” We want to bring great books, great stories, to hungry readers. The fact that all of our books are in translation—that’s an added extra, but the task remains the same.

MJ: Despite the continual churn of doomsday stories about books, new publishers continue to enter the field. Are these acts of faith by heady idealists or something else?

RU: I think the publishing industry is going to look a lot different in ten years than it does now, or than it did even two years ago. Today, you can start a publishing house with a specialization—say, literature in translation, or even narrower, French crime novels or Arabic science fiction—without needing to raise a huge amount of capital, and with hard work you can find an audience. Reading is like taking a vacation, and there are plenty of adventuresome travelers looking to taste food in the local market, hear live music at an out-of-the-way bar, learn a few words of the language, and maybe even have a romance with that woman from the fish restaurant, or the man who drove the bicycle taxi . . . Publishers act as travel agents, in a sense. And a small boutique publisher, who really knows one area very well—well, I think there will always be a demand for that.

MJ: Why limit your enterprise to translated books? Don’t you need at least a few more commercial titles to stimulate earnings?

RU: We’re just starting out now, finishing up our first season, and we’re quite happy with the way things have been going so far. In the future, we may find that we do need to publish more commercial titles—but one thing we’re out to prove is that literature in translation can be commercial. I think Americans are interested enough in other cultures to support that.

MJ: I agree. So of all the literature awaiting translation into English—and we know that’s a vast pool—why did you choose The Good Life Elsewhere?

RU: As a Phd candidate in Slavic literature, I have read lots of Russian novels in my life and I know that Russian literature offers a vast and quite frequently very funny landscape. And I worry that what most people know in the States is only the long and “serious” stuff from the nineteenth century. I mean, can you imagine if most people still thought of Dickens, and only Dickens, when they talked about British literature? Sure, it’s there, and it’s worthwhile, but there’s also a whole lot more. So I wanted to find something unusual for an American audience used to Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Solzhenitsyn—all great writers, but just the tip of the iceberg in terms of diversity of writing.

MJ: Vladimir Lorchenkov strikes me as a good choice. Tell us about him. What will we not find online?

RU: Lorchenkov is a very funny man. You can read one of his stories, “I Came to Spit on Your Graves,” on our website, to see what I mean. But he’s also a serious thinker, and he’s not afraid to speak his mind—albeit, almost always with a good bit of irony. He had an editorial in the New York Times recently about the situation in Eastern Europe called “Moldova, the 51st State?” Lorchenkov is a man who inhabits the world of the absurd and uses his talents to bring hypocrisy to readers’ attention. Even his emails are like a marathon race where every half-mile there’s another joke, another pun, another quip.

MJ: Lorchenkov is a native Moldovan, yet he writes in Russian. Is this typical of Moldovan literary authors? Is there much written in Moldovan? Can you tell us anything about the Moldovan literary scene?

RU: I’m afraid to say that I don’t know much at all about Moldovan literature. However, it’s not uncommon in the former Soviet republics that many writers are writing in Russian since (a) it’s a language that’s most easily spread across borders, and (b) if they grew up in the Soviet Union, they learned to read and write in Russian as children and were exposed to Russian literature in school and the surrounding culture, and (c) they might be ethnic Russians, in which case it’s their native tongue. Plus, if you write in Moldovan, you’re completely dependent upon translation to reach any significant readership. But if you can write in Russian, you have an immediately available audience. Over a quarter of a billion people speak Russian worldwide—that’s the fifth most spoken language in the world. No matter what side of the argument about the globalization of language and the marginalization of “minor” languages you’re on, those are hard numbers to argue with.

MJ: This book is very humorous, but the humor is of the tongue-in-cheek variety and not heavily dependent upon metaphor. Instead, there are many similes. Metaphors are famously difficult to translate, with the exception of body metaphors. Did the manuscript come to you fairly free of metaphors, or did you confront and transform them in translation?

RU: Chapter 11 is a great example of that. There’s this grotesque, tragic, funny recipe for kidneys that appears in the chapter, which is written in the voice of a woman who has inadvertently caused her husband’s death by cooking the organs he needed for a transplant. Here’s a sentence: “When [the kidneys] are boiled and become as soft as you were a week before your wedding, ruthlessly cut them with a knife sharp as fury, cold as ice, grey as steel.” Maybe because so much of Lorchenkov’s humor is exaggerated, it’s satire, it’s so offbeat, simile is more apt than metaphor. With simile you can say, “You are as dumb as a horse, as ugly as a turkey, as stubborn as an ox, as dirty as a pig.” With metaphor, there’s a limit, and it’s somehow meaner: “You are a dumb horse, an ugly turkey, a stubborn ox, a dirty pig.” That’s not funny; that’s cruel.

MJ: In the often over-the-top humor, Lorchenkov has some fun with clichés. For instance, at the beginning of chapter 6, when the villagers are training to be curlers, a leader is yelling, “Train like a grunt, conquer like a general. The bullet flies but a sword never lies. You want to go to Italy, don’t put the cart before the . . . I mean, you’ve got to push that stone!” Do these translate easily from Moldova to the US, or did you have to use substitutions?

RU: Clichés are often difficult because the ideas are always universal but the specific examples used to illustrate those ideas are almost always local. For instance, in Russia you can say “Baba s vozu—kobyle legche” [Баба с возу—кобыле легче], which means, approximately, if you throw the woman off the cart, the horse will have an easier time. In other words, this is close to Bob Marley’s “No woman, no cry.” Here, the Russian cliché is much more, let’s say, colorful. So, while pretty much every language has a way to tell a man, “You’ll be alright on your own,” some tongues do it better—or worse—than others.

As for military clichés—unfortunately, they are everywhere, since war is a part of everybody’s history, every nation’s past. I would bet that you could find a match for “Train like a grunt, conquer like a general” in any language you looked at.

MJ: There’s a fun line late in the twelfth chapter: “‘Between the devil and the deep blue sea,’ said the new consul, demonstrating his knowledge of international idioms.” Here the author comments upon how people portray themselves through their knowledge of international expressions.

RU: That was actually an instance of me finding an equivalent, since the Russian expression in the original has no meaning as a straight translation. So I found an expression that is well known, means the same thing, but is not in such regular use. I know the expression “between the devil and the deep blue sea,” but I’ve never heard a native American English speaker use it. It’s more likely to be used by somebody learning English from a textbook who has memorized the phrase and is so proud to trot it out in conversation. For instance:

“Hello, Ivan, how are you?”

“My boss says I must work late, but mother-in-law has spent all day cooking dinner for me and family. Truly I am between devil and deep blue sea!” [Should be read with a Russian accent.]

MJ: Like clichés, similes translate more easily across cultures than do metaphors. In chapter 12, Consul Buonarotti at the Italian Consulate says of Moldovan immigrants, “They’re like spiders. They’ve invaded and now you can’t do anything about them.” Is this is a literal translation?

RU: Yes, that was a literal translation. Usually Lorchenkov made me work much harder. His language is so versatile and playful that often there are several conversations happening at once. You realize that there’s not just one butt of every joke. There are two or three victims felled by each satirical bullet in Lorchenkov’s work.

MJ: I’ve now read two of your releases, The Good Life Elsewhere and Shemi Zarhin’s Some Day, and found them both hard to put down (I feel no obligation to finish something that doesn’t pull me back with magnetic force). So you’re two for two with me. How do you choose your books?

RU: I’m glad to hear it! We find our books in a variety of ways—sometimes through agents (that’s how we found The Good Life Elsewhere), sometimes through foreign publishers—or agencies like the German Book Office or the Institute for the Translation of Hebrew Literature—and sometimes through friends (which is how we found Some Day). Between Michael and me, we read French, German, Russian, Polish, and Hebrew (albeit slowly), so we can cover decent ground. Do you have any recommendations?

MJ: I’m teaching a class this semester focusing on Andrés Neuman’s work. We’re reading several of his short stories and his incredible novel Traveler of the Century. I wish his travel essays, Cómo viajar sin ver, and Década, his collected poems, were available in English.

Ross Ufberg is cofounder of New Vessel Press, a publishing house specializing in foreign literature in translation. Also a translator, his most recent translations include Vladimir Lorchenkov’s The Good Life Elsewhere and Beautiful Twentysomethings (2013), the literary memoir of Polish writer and rebel icon Marek Hłasko. Ufberg is a PhD candidate in the Slavic Department at Columbia University.