Erasmus’ Treasury

Desiderius Erasmus (1466?–1536) made big books from little things. A literary lapidary, he compiled proverbs, anecdotes, metaphors, and quotations. He called metaphors “jewels” and judged that “in the domain of literature, it is sometimes the smallest things which have the greatest intellectual value.” He excavated “precious stones from the inner treasure-house of the Muses” for the delight of scholars everywhere.[1] These were his Adages.

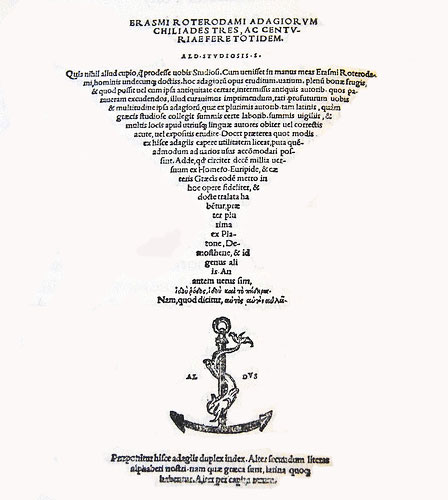

Between 1500 and 1536 he published twelve editions of his Adages, all intended to contribute “to a rich and attractive style.”[2] The publisher of the first edition advertised it as a thesaurum, a treasury of gems, useful to aspiring scholars eager to embellish their letters and conversation with impressive bits of Latin and Greek. Erasmus expected it would sell well and it did. His Adages made Erasmus internationally famous years before he published his controversial New Testament.

With each new edition Erasmus added adages. The first edition (Paris, 1500) had 953. For his Aldine edition (Venice, 1508), he arranged adages in chiliads, or thousands. His last edition (Basel, 1536) topped 4,000. The collection presents the wit, slang, and idioms of Greece and Rome in a glittering jumble.

In any language, twenty-first-century readers of the Adages join a brilliant company. Luther, Grotius, Milton, and Gibbon read the Adages in Latin. Montaigne decorated his Essais with Erasmus’ jewels. Francis Bacon copied adages in his commonplace book and made his own on their model. Shakespeare appropriated adages for Romeo and Juliet, Cymbeline, King John, Two Gentlemen of Verona, and Henry VI, Part 3.[3] “Hoist by his owne petar” (Hamlet 3.4.207) contemporized Erasmus’ “Suo sibi hunc iugulo gladio,” slain by his own sword.

Under the term “adages,” Erasmus admitted several kinds of short-form literature: proverbs, of course, such as “there is nothing worse than self-deception” and “you make an elephant out of a fly.” There are also “remarkable metaphors, witty sayings, noteworthy epigrams, unusually delightful allusions, and poetic allegories.” Erasmus included flatteries, ripostes, and ridicule, useful for professional advancement. He gave the nicknames for several kinds of fool and scoundrel. He collected stereotypes of Germans, Flemings, Spaniards, and French.

Erasmus included flatteries, ripostes, and ridicule, useful for professional advancement. He gave the nicknames for several kinds of fool and scoundrel.

When he found an adage he didn’t like, he inserted it anyway. He had a collector’s excuse: “I could hardly bring myself to write out such rubbish, were I not determined to perform my allotted task at all points.” He did not disdain an occasional proverb penned by Renaissance Italians.

Since the meanings of classical adages could be foggy or opaque, Erasmus supplied commentaries. A “Myconian head” was bald, “Azania ills” are useless toil, “Megarian tears” are forced and phony. “To sing a palinode” was to reverse your opinion, and “an eagle’s old age” applies to old men who drink more than they eat. He wrote with a wink when he included “Ne unquam viri senis”—never look in the ass of an old man—and demurred, “The image is too indecent for me to be willing to expound it.” No need to.

Many adages remain familiar: “fire follows smoke,” “hunger is the best sauce,” “a liar should have a good memory.” Some changed meanings sharply by the time they reached us. “To look beyond oneself” once meant to agree publicly with an opinion you privately scorn. To “throw cold water” on a man was to refresh him. A “sycophant” was an informer. “Thumbs up” meant rejection, “thumbs down” approval. A “flash in the pan” was a harmless threat. Who “sets up a web” begins a task skillfully.

Erasmus included adages that stumped him, like “we play cities” and “a Daulian crow.” He was happy, he said, to leave it to his readers to guess.

Erasmus usually cited sources. “War is sweet for those who do not know it” was traced to Pindar, and “I hate a drinking companion with a good memory” to Martial. “To show the middle finger” requires no commentary, but it is charming to see it has a classical precedent.

After 1508 the Adages became Erasmus’ most flexible and expandable carrier of random ideas. Adages provided occasion for comments about church and state, compliments to patrons, and admonishments to popes and princes. Under the adage “Labors of Hercules,” Erasmus wrote to account the time and trouble it took to collect his adages and explain them. He complained about the frustrations he encountered, defied the ingratitude of critics, and dared them to do better.

As the number of adages grew, so did his commentaries. Three lines long in 1500, the “Labors of Hercules” grew to eight folio pages in 1536. Simple comments became learned essays, some sufficiently important to be published separately.

Until now, only selections had been translated into English. The first complete English translation was incomplete until this year, when volume 30 of The Collected Works of Erasmus (hereafter CWE) appeared, the last of seven volumes of the Adages.

The set required decades of devotion from its scholars and publisher. In six volumes published between 1982 and 2006 (CWE 31–36), the University of Toronto Press published the first complete English translation of the 1536 Adages, all 4,151 of them, with Erasmus’ commentaries and editors’ notes. Now the first comes last. CWE 30 is a faithful translation by John N. Grant (University of Toronto) of Erasmus’ first edition as it was enlarged and reprinted in 1506. Why now? Why do we need an English version of the early Adages with its fewer adages and sparse Erasmus? Why this meager beginning when the fullness of the 1536 edition already exists?

Several early Adages deserve revival on political blogs, such as “Colophonian wantonness” (powerful men who mistreat the poor) and “Cilician profits” (ill-gotten gains).

Because the first edition continued to be reprinted, in several cities. It held its own against imitators and competed successfully with its larger progeny. It is a promise fulfilled: with remarkable patience and foresight, CWE 32, published in 1982, refers readers to the prolegomena in CWE 30. In the early Adages, Erasmus tells us what he first thought about “A friend is another self,” “Flattery wins friends and truth engenders hate,” “Extreme right is extreme injustice,” and “Old age itself is sickness,” adages that he reconsidered as he aged. Several early Adages deserve revival on political blogs, such as “Colophonian wantonness” (powerful men who mistreat the poor) and “Cilician profits” (ill-gotten gains).

In Erasmian fashion, CWE 30 is laden with editors’ commentary and source notes more exact than Erasmus’ own. Footnotes and a concordance link the 1506 adages to the 1536 sequence. An appendix provides a welcome survey of Erasmus’ sources that summarize what the expanding editions reveal about his reading, rereading, and taste.

Years ago the editors of the CWE planned that CWE 30 would contain indexes to all seven volumes, a task that awaited publication of CWE 31–36. CWE 30 has eight (!) indexes, all prepared by William Barker (Dalhousie University) and all encompassing the adages of CWE 31–36; oddly, there is no index for the adages of CWE 30. The first index lists Greek adages; the second, Latin adages. Then comes an index of “Early Modern English Proverbs,” keyed to M. P. Tilley’s Dictionary of Proverbs and the third edition of the Oxford Dictionary of English Proverbs. This is followed by Erasmus’ 1536 topical index; the same, alphabetized; a full English index; a supplementary index of names, uniquely indexed to CWE volume and page numbers; and an index of scriptural references. Users of the Adages will be glad to have them all. Except for the supplementary name index, all entries are keyed to Erasmus’ own numbering, enabling use with other editions, including Latin ones. The 130-page index of English terms opens Erasmus’ enormous thesaurus to readers seeking adages about friendship, money, women, war, etc.

In its bright bazaar you can skip, sample, and linger as you like, soak up poetry, sneer at tyrants, enjoy fools in their folly and the wisdom of kings.

The Adages appeals to every littérateur in need of august refreshment. No matter how narrow your study, the Adages will enlarge it. In its bright bazaar you can skip, sample, and linger as you like, soak up poetry, sneer at tyrants, enjoy fools in their folly and the wisdom of kings. In his Adages, Erasmus invites you to browse, scoff, wonder, ponder, and meanwhile tip a glass or two.

Waiting for CWE 30 was a matter of a few years. Tantalized by partial translations, English readers have waited centuries for a complete Adages. At last we have it, dense, delightful, and whole. The Toronto Adages is a major accomplishment, five hundred years overdue.

Urbana-Champaign, Illinois